Women are a focal point in Malaysian politics today, with some recent discussion of their ability as voters to decide election outcomes. But this has not translated into their increased representation at a political level, demonstrating the continuing prevalence of patriarchal thought in the political sphere.

The ability of women to exert political influence is not remotely new in Malaysia, and certainly not amongst ethnic Malays who make up roughly half the population. Although the rulers of Malay sultanates were often male, there are some notable exceptions, among them the four queens of 17th century Patani and Cik Siti Wan Kembang and her adopted daughter Puteri Sa’dong of Kelantan.

In the 17th century literary text Sejarah Melayu, women are prominently depicted in the royal genealogies as “beautiful and bountiful”, to borrow the social historian Lenore Manderson’s description. But they are also frequently depicted as a “power behind the throne”; one story in the text describes the action of Sultan Mahmud Shah’s mother who, from her listening position behind a door, directed her son to appoint her brother as his chief minister. Even in smaller-scale village politics, there is evidence that women played a significant role in decision-making processes. In Negeri Sembilan, a matrilineal model formed the basis of Minangkabau society.

During colonial rule, gender was a key element in establishing power. The construction of racial hierarchies depended on the feminisation of “the native” – that is, the dichotomy of the rational and progressive European versus the lazy, effeminate Malay (with ethnic groups being accorded placements as per their assumed natural behaviours). Such hierarchies were often explained in familial terms, with the coloniser as its “head”. A woman’s place in the private sphere was made out to be natural and universal; similarly, the position of the Caucasian male sitting unchallenged at the top of the pyramid was to be assumed.

If deconstructing these ethnic pecking orders was one of the promises of independence, then so too was the promise of gender equality. In a 1949 speech, then United Malays Nationalist Organisation (UMNO) leader Onn Jaafar said that women’s voices would be “as powerful as that of the men – the voice of both will determine the shape of the administration of the country.”

More than six decades later, Malaysian politics and society remains heavily ethnicised, and the gendered nature of ethnic politics has inevitably meant that women don’t have an equal say in the running of the country. Despite a declaration by Prime Minister Najib Razak earlier this year that there was no gender inequality in Malaysia, women are outnumbered in the current Malaysian Parliament eight to one.

Certainly, there have been some encouraging signs in the intervening years. The 2008 elections saw the most number of women candidates run for seats, and at nearly 11%, the percentage of women representatives in Parliament today is definitely an improvement on just under three per cent in 1959.

But it is still a long way off the 30% target that Malaysia committed to when it signed the Beijing Platform of Action in 1995, and, according to the World Economic Forum’s 2010 Global Gender Gap Index, the current figures places the country behind Southeast Asian neighbors the Philippines, Indonesia, Vietnam and Cambodia.

There is also the question of whether or not women’s voices are a part of political decision-making. The lack of women representatives has, women’s groups have argued, meant that the government has been slow in acting on gender-specific issues. When earlier this year Najib took over the women’s ministry portfolio rather than appointing a replacement to the outgoing minister Shahrizat Jalil, women’s groups expressed dismay, noting women’s issues had “languished” when it had previously been under the Prime Minister’s purview.

A 2003 governmental report agreed that women were underrepresented in the political arena, but said that the government was “not overtly discriminatory”. There were, the report continued, other reasons that women were not well represented – chiefly that there was a shortage of qualified women. Shahrizat agreed, noting in a New York Times report that the ruling coalition had always fielded female candidates, but that there were “just not enough”.

The report also noted persisting mindsets about the place of men and women in the political and private spheres. I have previously written how uniquely harsh treatment of “iron women”, such as 1950s leader Khatijah Sidek and more recently former Trade Minister Rafidah Aziz, demonstrate that women who venture into politics and positions of leadership can expect gendered criticism. With there being no gender quota in Parliament, and only five seats of 55 on the UMNO Supreme Council being reserved for women, the immediate prospect for increased women’s representation in politics is bleak.

The next national elections must be held in the country before June 2013, and they will be the first for Najib since his assuming the premiership. His predecessor Abdullah Ahmad Badawi had been dumped by his party following its “defeat” of sorts in the 2008 elections. At the ANU Malaysia & Singapore Update earlier this month, Bridget Welsh of the Singapore Management University predicted that the opposition front, Pakatan Rakyat (PR), would win the popular vote in these elections. During the same event, Clive Kessler of the University of New South Wales noted that anything less than a resounding victory for Najib would make his position tenuous.

With the possible outcome too close to call, both sides are ramping up their efforts to win voters over. Last month, online news portal The Malaysian Insider reported that women working at home and young voters – “fence sitters” – would decide the result of the next election. A week later, it ran an article titled “Young lady, your country needs you!” which, amongst other things, detailed the results of a straw poll of young women voters. Even the most apolitical young woman voter (depicted as liking shopping and worrying about her relationship status), it said, had concerns about the economy (specifically whether or not she could afford a particular handbag).

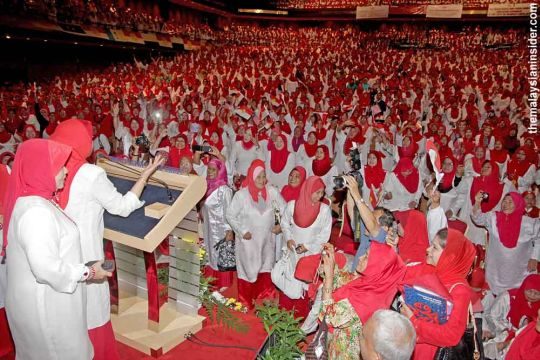

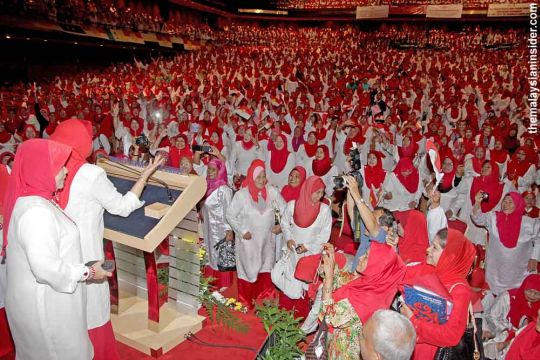

Malaysian women are hardly apolitical, and no political party knows this better than UMNO. Women have remained strong in their membership base, with their numbers forming over half of all members at different points in the party’s recent history. The ability of the women’s wing to canvass votes for the party, particularly in rural areas, is well-documented, to the point where PR leader Anwar Ibrahim recently called on PR women’s wings to strengthen its base in rural areas so as to be more competitive there.

Women can be courted, but calling shots as political leaders – no. With Malaysia at a crossroads, the political agenda must now focus on mechanisms that increase women’s representation in politics. This must become a national priority, and not an optional extra, as gender equality remains an unfulfilled promise.

Dahlia Martin is a PhD candidate at the School of International Studies, Flinders University. Her thesis, titled “Family and the Melayu Baru: motherhood and Malay Muslim identity”, investigates the position of motherhood in Malay nationalism.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss