- Diaz Hendropriyono and Maruarar Sirait, both from Jokowi’s campaign team, pose with Fadli Zon, Deputy Head of Prabowo’s party Gerindra, for a selfie. The three attended a ceremony last night in South Jakarta in which Hendropriyono was awarded a professorship in Intelligence from the State Intelligence Institute. Jokowi, Megawati and former-military-general-turned-Hanura-head, Wiranto were all in attendance. Photo credit: Diaz Hendropriyono’s twitter feed.

The Indonesian Electoral Commission will soon announce the results of April’s legislative elections. Parties will most likely announce their candidates for the July 9 presidential elections after that. Human rights is likely to be a major part of the debate. On the eve of a presidential election where Joko Widodo and Prabowo Subianto will face off as major contenders, let’s examine the record of both.

The record of Prabowo Subianto has been the most subject to politicization, but also critical debate. As former commander of the army special forces (Kopassus), he was implicated in the kidnapping of pro-democracy activists in 1997/98 when the New Order was on its last legs.

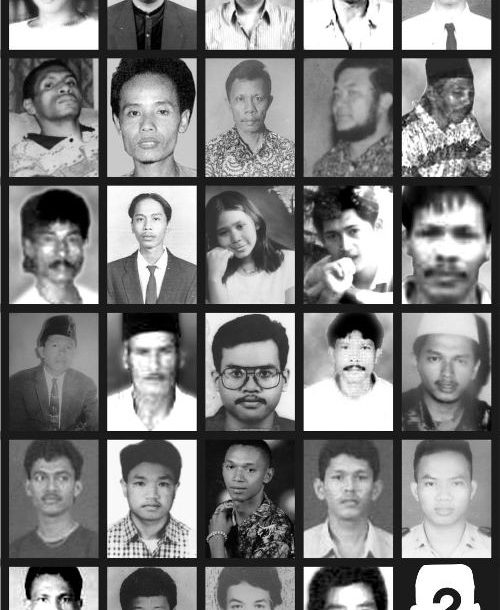

While 9 were found alive, 1 was found dead, 13 have never been found and are considered “disappeared.” The disappeared are categorized in three groups. First, student activists from the Indonesian Student Solidarity for Democracy (SMID) including Petrus B. Anugerah, Herman Hendrawan, Suyat, Wiji Thukul. Second, pro-Megawati activists including Yani Afri, Sonny, M. Yusuf, Noval Al Katiri, Dedi Hamdun and his driver Ismail. Third, persons witnessing the May 1998 riot such as Hendra Hambali and Yadin Muhidin.

Two years ago, speaking in exclusive interview with TV anchor Dalton Tanonaka, Prabowo denied that he ordered the kidnapping and torture of the activists. “I (would) never order torture (because it’s) completely against my policy. I never ordered the so-called “kidnapping” or detention.”

This statement has been refracted in different ways by other members of the Prabowo camp. This month, retired former chief of staff of the Army Strategic Command (Kostrad) Major General Kivlan Zen insists that Prabowo only “secured” nine activists who were subsequently returned alive. Kivlan accused a Prabowo “rival” of conducting a side operation, disappearing activists who are still missing. Last month in April, Fadli Zon, Deputy Chairman of the Great Indonesia Movement (Gerindra) denied Prabowo’s responsibility in the disappearances. Fadli admitted that a special unit called “Rose Team” run by Prabowo had arrested nine activists and returned them–but he said that the other missing activists were abducted by an “unknown perpetrator”.

Both Kivlan and Fadli’s statements accept that Prabowo kidnapped activists. They simply place Prabowo in a higher moral category compared to his rival, who they imply is Prabowo’s fellow contender, Chief of Indonesian Armed Forces (TNI) General Wiranto. Wiranto, they argue was the real mastermind of the disappearance of the other 13 activists.

Moving away from the hubub of the campaign let’s track back to the results of the official investigation. In early 1998, the disappearance of activists generated intense public pressure demanding the government return the missing activists and punish the perpetrators. Meanwhile, the Indonesian Armed Forces (ABRI) was forced to establish a Council for Officers Honour (DKP) on August 3, 1998 to investigate implicated officers.

Two weeks later, Chair of DKP Gen. Subagyo Hadisiswoyo recommended to the chief of Indonesian Armed Forces (ABRI) Gen. Wiranto that Prabowo, Major General Muchdi Purwopranjono, and Colonel Chairawan, should be brought before a military trial (See Kompas, “DKP: Bring Prabowo etc to Military Trial,” 15 August 1998 page 1).

- Current Presidential candidate, Prabowo Subianto (left) and Muchdi Purwoprandjono (right). In August 1998, Prabowo (left) headed up Kostrad and Muchdi was the Commander for Kopassus. Both were dismissed from the military for the disappearances of pro-democracy activists. Photo credit: Reuters.

The trial never took place. On August 24 1998, Wiranto fired Prabowo from military duty, citing the DKP’s recommendations. It’s still open as to whether these officers will be brought before a military trial”, he added. DKP member Lieutenant General Agum Gumelar said that Prabowo admitted to have kidnapped nine persons. (See Kompas, “Prabowo was fired: Muchdi and Chairawan was off duty,” August 25 1998).

A later Joint Fact Finding Team (TGPF) established by President BJ Habibie stated clearly that “… In the case of abduction, Lieutenant General Prabowo and all actors involved must be brought to military trial..” (See Final Report of Joint Fact Finding Team on 13-14 May 1998, recommendation no. 2, November 3rd 1998, page 19).

More recently, in 2006 when the National Human Rights Commission (Komnas HAM) handed over its report on the disappearances of 1997/1998. Their key finding is that 23 activists, were forcibly kidnapped by Kopassus which Prabowo headed up. They confirmed that nine activists were severely tortured, one activist was killed (Gilang) and thirteen remains disappeared. Another important finding is that some of kidnapped activists were held together in the same military detention facility with those who disappeared. Some of them testified that they met with Yani Afri aka Rian, one of the 13 people still missing.

In September 2009, the House of Representatives supported the KomnasHAM report and issued recommendations to President Yudhoyono to establish an ad hoc human rights tribunal. However, Prabowo and other implicated military officers were not brought to trial. A fair and impartial court is needed to reveal and confirm the role of implicated former army generals, including Prabowo in such past atrocities.

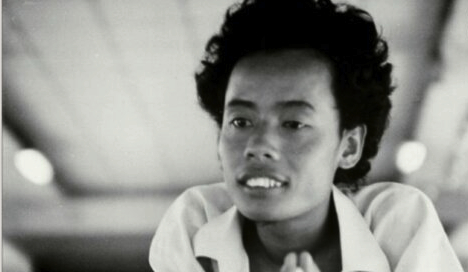

What about the second candidate, Joko Widodo? How does his human rights record fare? One interesting incident happened three weeks ago when Gerindra deputy Fadli Zon attacked Jokowi by writing a poem. When journalists asked Jokowi if he read the poem, Jokowi answered that he prefers poetry by Wiji Thukul, especially his famous poem ‘Peringatan’.

- Wiji Thukul is an Indonesian poet who went missing in 1998 during the period of protests that led to the fall of the New Order. He lost his sight in one eye after being hit with a rifle butt during a workers protest in 1995. His poems exhorted people to speak truth to power.

Wiji Thukul is a leftist poet who disappeared in the late 1990s. Certainly Jokowi is sympathetic to the family of Thukul, visiting them in Solo and offering assistance. Along with Jokowi’s visit to Papua, this seems important. However perhaps only because Jokowi has not yet elaborated a clear policy statement on human rights. Even worse, some former army generals who have blemished records now have Jokowi’s ear. These include Lieutenant General (ret) AM Hendropriyono and General (ret) Ryamizard Ryacudu.

Under the New Order, Hendropriyono was a high ranking military leader but went on to become head of State Intelligence (BIN) under Megawati’s government. Hendropriyono and in particular, his son Diaz Hendropriyono, have major roles in Jokowi’s election success team despite the tensions this has caused with other pro-democracy activists like Teten Masduki and security expert like Andi Widjajanto on Jokowi’s core campaign team, “Team 11”.

- Hendropriyono (left) and Prabowo (right) at a book launch last year. Yesterday, detik,com published rumours that Hendropriyono will be made head of Jokowi’s success team. Photo credit: Antara news.

While Commander of 043/GarudaHitam Resort Military Command in Lampung in 1989, Hendropriyono was implicated in an early morning military attack against hundreds of civilians who accused of trying to establish an Islamic state in the backwoods of Cihideung, Talangsari, Central Lampung. The attack on three villages left at least 27 people dead, 78 missing, 5 people were kidnapped, and 23 people were arrested and detained arbitrarily (Kontras, 2008).

As head of State Intelligence Body (BIN) AM Hendropriyono and his Deputy V of BIN, Muchdi Purwopranjono are also implicated in the assassination of human rights defender Munir Said Thalib. In 2004, President Yudhoyono established a fact finding team on the murder of Munir and in its final report the team recommended the police investigate the then director of Garuda airways Indra Setiawan, BIN Deputy Muchdi and head of BIN AM Hendropriyono. In 2008, Indra was indicted and convicted guilty.

- Munir was a human lawyer who founded KontraS. He was poisoned on a Garuda flight from Jakarta to Amsterdam in September 2004. Hendropriyono and Muchdi have both been implicated in his death.

This is where the human rights records of the two presidential contenders become weirdly intertwined. Muchdi served as a commander of Kopassus under Prabowo–and in the trial for the Munir case, the prosecutor alleged that Muchdi’s motive for killing Munir was because the young human rights activist had exposed Muchdi’s role in the kidnapping of the 23 pro-democracy activists leading to his dismissal (along with Prabowo as head of Kostrad) from Kopassus.

- Muchdi Purwoprandjono was head of Kopassus in 1998 and fired along with Prabowo for the disappearance of student activists in 1998. In 2004, he was Deputy V of BIN under Hendopriyono. He has been implicated in the death of Munir and was held in police detention for 8 months, however he was ultimately cleared of all charges.

There has been no further investigation into the role of Hendropriyono in Munir’s death. During his life, Munir’s struggle for justice also targeted Hendropriyono.

Munir represented hundreds of the families of the victims of 1989 Talangsari case. Munir lodged a complaint to the State Administrative Court when Megawati appointed Hendropriyono head of BIN in 2001. Munir also criticized Hendropriyono for reporting 20 activists as being a danger to the 2004 election.

What chance does justice for Talangsari have if Jokowi maintains his close ties with AM Hendropriyono? What will Jokowi do if the widow of Munir, Suciwati, asks him to act on the presidential fact finding team that that pointed to the involvement of AM Hendropriyono as chief of BIN in her husband’s murder?

Equally problematic is another army general in Jokowi’s circle, Ryamizard Ryacudu, a former army chief under consideration as Jokowi’s Vice President. Ryamizard has been widely known for his hard-line stance on human rights and separatism without considering government policy.

- Ryamizard Ryacudu is a former military general known for his hardline stance on separatism. He is known to be close to Megawati and served as chief of staff under her term. He has been touted as a possible Vice President for Jokowi.

As army chief, Ryamizard has frequently insisted that the NKRI (roughly: ‘national unity’) project can only be secured by giving the military a greater, and indeed a decisive, role in fighting separatism. During martial law in Aceh, that killed thousand lives, the army under him was against negotiating a peaceful solution. “Our job is to destroy GAM’s military capability. Issues of justice, religion, autonomy, social welfare, education–those are not the Indonesian military’s problems”, said Ryamizard in an interview with TIME Asia, June 2, 2003.

In April 2003, after military officials were convicted for the murder of Papuan independence leader, Theys Hiyo Eluay, Ryamizard, as chief of staff of the army, made a public statement saying that “the law says they are guilty. They are punished. But for me they are heroes”.

Pairing Jokowi with a vice president like Ryamizard might see any future government he forms choosing a more military based policy in managing separatism. With Ryamizard, Jokowi will likely to lose support from Acehnese and Papuan voters.

It’s unclear how influential these former army generals are on Jokowi, but neither is it clear why Jokowi has surrounded himself with them in the first place. At this stage, Jokowi needs someone who could play a role in effecting peace in Papua, as happened with the Free Aceh Movement (GAM) in Aceh. With friends like these, how will Jokowi decide on human rights issues, let alone to answer victims’ questions on bringing perpetrators to justice?

All in all, it’s a pretty depressing presidential choice for voters concerned about human rights issues. Human rights abusers appear to have maintained their power and influence at the centre of Indonesian politics. As the elections draw closer, the media, civil society groups and the electorate at large should put pressure on both the Prabowo and Jokowi camps to clarify their positions on human rights abuses and they should demand an explanation for why hard-line generals of the past should be given any role in determining Indonesia’s future.

…………………

Usman Hamid was a student activist in 1998 and is cofounder of Change.org Indonesia and is currently an MPhil candidate in the Department for Social and Political Change at the Australian National University. You can follow him on Twitter @UsmanHAM_ID.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss