* with apologies to Roger Benjamin

Like many academics across Australia, the members of PoP have watched with concern and dismay the unfolding story about the ministerial censorship of successful Australian Research Council (ARC) grants. In case you missed it, Senator Kim Carr revealed last week that in 2017 and 2018, the then-Minister for Education Senator Simon Birmingham had blocked eleven successful ARC grants (totalling $1.4m) without reason. This was despite the fact that the applications, which took hundreds of academics hours to prepare, had passed the rigorous ARC peer review process and had been deemed worthy of funding.

A panel of experts in the field thought this research was worth funding, but Senator Birmingham did not. Tellingly, all the blocked grants were in the humanities. There are no signs of contrition. In fact, quite the opposite, with Birmingham taking to Twitter to defend his decision to block these projects, and singling out one in particular for public shaming (‘I’m pretty sure most Australian taxpayers preferred their funding to be used for research other than spending $223,000 on projects like “Post orientalist arts of the Strait of Gibraltar”’).

Over the past week, a number of educational and disciplinary associations have come out in protest against this ministerial interference – see for example these statements by Universities Australia, the Australian Historical Association, the Asian Studies Association of Australia (ASAA) and the Council of Australian Law Deans. As the ASAA statement says,

The Australian Research Council uses a rigorous process of peer review to allocate its grants. Academics compete through this process, and devote time to assessing applications voluntarily, on the understanding that applicants compete on a level playing field and that their applications are assessed purely on the basis of scholarly merit. This process contributes greatly to the excellence and international reputation of research in Australia. It is very disappointing to learn that 11 applications were vetoed, not as a result of scholarly review, but by arbitrary exercise of political discretion. Such interference undermines the integrity and transparency of Australia’s system of peer review, and harms Australia’s international reputation for research excellence.

The story is also gaining traction overseas, with Nature now weighing in on the issue of political interference and the reputational risk to Australia as a desirable place to do research.

The members of PoP are PhD candidates and (very) early career researchers. We are yet to embark upon the complex ARC application process; those particular pleasures lie ahead for us, if we are lucky. We have, however, benefited from scholarships funded by the Australian Federal Government – that is, Australian tax-payers have funded our research. I received Commonwealth funding to complete my PhD, and was also the beneficiary of a number of travel and fieldwork grants throughout my candidature. I could not have done my research without this funding. My view is that if you’re interested in learning more about why my research is deserving of time, attention and Australian tax-payer dollars, I have a responsibility to share that with you. Working as an academic, and receiving funding support to do so, is an absolute privilege, and I believe it comes with a responsibility to communicate our discoveries to the public.

But, and it is this point that underpins my discomfort about Senator Birmingham’s decision to block successful ARC applications, research is inherently exploratory. Its value may be obvious to those doing the research but the outcomes might not be so clear, especially in the initial stages of a project. Often, as researchers – even, and especially, as junior researchers! – we don’t know what we are going to discover until we have spent some time mucking about in the academic weeds, getting a bit lost, going down research rabbit holes, and looking back on old problems with fresh eyes. What’s important is that scholars have the freedom to do this exploratory work without the fear that their work will be censored.

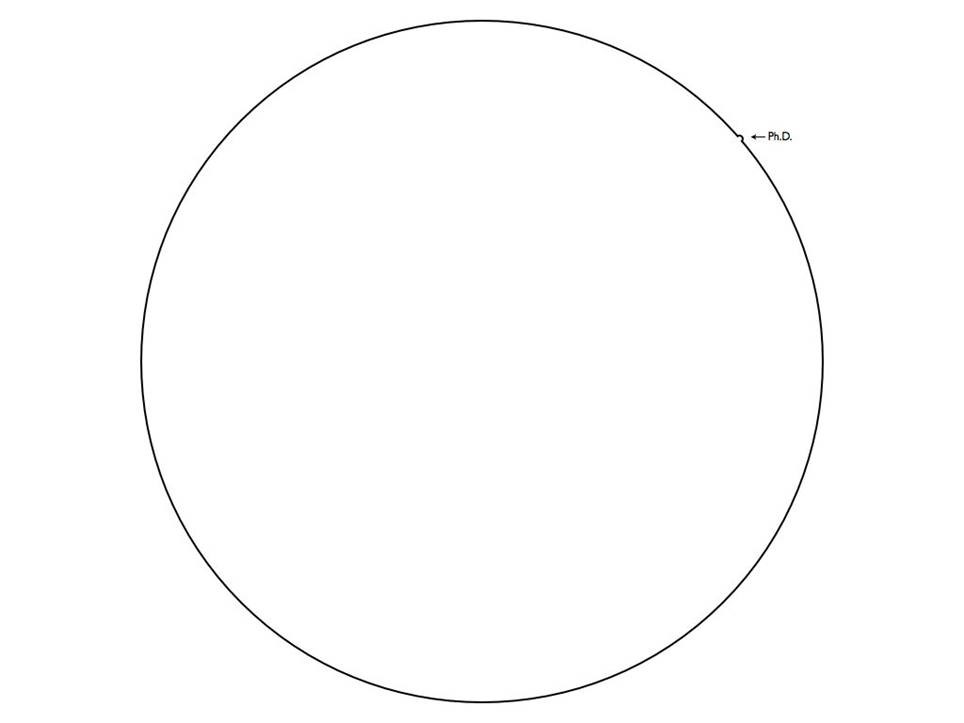

PhD in pictures. Image: Matt Might

For PoP, and especially for me, the blocking of eleven successful ARC grants is a little too close to home. That project Birmingham mocked, about the post-Orientalist arts of the Strait of Gibraltar? Well, it turns out that it’s from my home department here at the University of Sydney – the Department of Art History, which is celebrating its 50th year of teaching this very year.

As Professor Roger Benjamin, the academic behind the blocked application, explains, the project (the full title of which is ‘Double Crossings: post-Orientalist arts at the Strait of Gibraltar’) sought to examine ‘the way painters and photographers crisscrossed the 15 kilometres of the most politically contested water in the world – Europe to Africa, Muslim to Christian worlds – in search of arresting images of other cultures.’

Hearing this, I am immediately hooked. To me, Professor Benjamin’s proposed project sounds endlessly fascinating, and also important. Of course we should be funding this research, in which art is used as a lens by which to examine the relationships between power, politics, religion and place! Are these not some of the biggest themes of our time?

But not everyone feels the same way. I get it. I know this because of the blank looks I have received from my non-academic friends (and sometimes my academic friends, truth be told) about why I have devoted almost four years of my life to learning about a 9th century Arabian-style ship and the objects it was carrying. This stitched-hull ship (that’s right, no nails – what’s not to love?) sailed across the Indian Ocean before being wrecked near the Straits of Malacca with a full cargo load of Tang dynasty ceramics.

This sort of soft and fuzzy research is not perceived to be as ‘legitimate’ as a project on counterterrorism, or child malnutrition, or drug resistant respiratory diseases. In fact, unless I am speaking with a maritime archaeologist or ceramics expert, the most common reaction when I tell people about my research is a puzzled ‘Oh…! Er, why did you choose that? I guess you always did like swimming.’ The onus is then on me to explain – preferably as quickly as possible, before they flee – why I am interested in something so seemingly obscure. To do this, I use words that grab attention (‘shipwreck’, ‘controversy’, ‘profit’) and talk about how my research has the potential to change how museums, those institutions in which we often vest our trust so unquestioningly, tell stories. Sometimes this leads to a discussion about what museums choose to display and what they choose to leave out, and about the responsibilities these institutions have to keep and interpret objects.

I know I am not saving lives here. And I don’t expect anyone else to be as enthusiastic about my research topic as I am. That’s why I am the one working on it. That is why Professor Benjamin brought his decades of experience to the process of developing a grant application about post-Orientalist arts at the Strait of Gibraltar. But if I can convince someone who knows nothing about my research topic to simply think critically about, say, the wall labels next time they visit a museum, and to reflect on the way objects are used to shape and obscure meaning, the past four years – and hopefully the next – will be worth it.

Follow the conversation on Twitter or Facebook!

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss