The elections scheduled in Thailand for 24 February 2019—unless, of course, there are further postponements—will be the country’s first since the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO)’s coup on 22 June 2014. The stakes are high. Riding on these elections is not merely who will assume government, but the very form of Thailand’s political system. Thailand’s palace, bureaucratic and military elites are clearly looking to consolidate their hold on power through the establishment of a semi-authoritarian regime. Within such a regime, the formal electoral process would be a method both to placate domestic political pressures, and to earn greater international legitimacy than what is possible under the current model of direct military rule.

Efforts to transition to a new regime type are, however, likely to be neither smooth nor easily successful, for several reasons that I will examine here. The state of Thai politics in the aftermath of the elections will be acutely tense, with power fragmented.

Elections under military rule: lessons from the past

There is a historical significance and particularity to the elections of 2019. To grasp that significance, we must acknowledge the specific context in which they are being held: they have been scheduled at a time when the junta’s hold on power remains firmly secure. Since 1957, Thailand has seen three rounds of elections where the incumbent government was a junta: the elections of 1969, during the era of Field Marshal Thanom Kittikachorn; the elections of 1991, under the government of Anand Panyarachun, who was appointed prime minister after the National Peace Keeping Council’s coup in 1991; and the elections of 2007, under the government of Surayud Chulanont, who came to power after the coup that overthrew the government of Thaksin Shinawatra in 2006.

Those three elections held under conditions of military rule led to instability and crisis. Beginning with the elections of 1969, the Sahaprachatai party (United Thai People’s Party), a military-controlled party, received the most votes of all parties—but still not enough seats to form government. It was forced into a coalition government with a number of small parties and independent MPs, while the Democrat Party spearheaded a rigorous opposition along with some other parties. Field Marshal Thanom, prime-minister-by-coup turned elected prime minister, found himself unaccustomed to governing through bargaining with other parties rather than absolute decree. In 1971, he enacted a coup against his own government, annulling the constitution and all political parties, and returned to unequivocal dictatorship once again. Rather than settling Thanom’s hold on power, however, the coup fuelled the disappointment of civilians and students and lay the backdrop for the mass uprising against dictatorship of 14 October 1973. Thanom’s own coup contributed, in the end, to the temporary fall of military rule.

The elections of 1992 followed much the same pattern. Once again, a military-aligned party, the Samakheetham party (Justice Unity Party), won the most seats of all parties, with its candidates comprised of provincial bosses exercising local influence (chao pho). And once again, the party still controlled less than half of all seats in the legislature, forcing it into a coalition government. When General Suchinda Kraprayoon, the coup leader, stepped up to assume the prime ministership, he was faced with a large number of angry protesters, who took to the streets. Suchinda’s government violently repressed the protest, resulting in many deaths and injuries, but eventually stepped down after intervention from the monarchy. This political tragedy is known as “Black May 1992”.

As for the 2007 elections, the Council for National Security (CNS) followed a relatively novel strategy: changing the electoral system, disbanding Thaksin’s party, and pressuring various factions from his outlawed Thai Rak Thai to defect and create new parties which the junta supported from behind the scenes. While the establishment hoped that such measures would lead to Thaksin’s defeat at the polls, the final election results proved the opposite: a landslide victory for his Palang Prachachon (People’s Power Party), while the parties supported by the junta received even fewer seats than it anticipated. Because traditional elites were unable to inherit power through elections according to their own strategy, the 2006 seizure of power has been called “a wasted coup”. It was also the beginning of a political war between coloured shirts, a prolonged conflict played out on the streets and intercut with violence.

If we look to history, it becomes clear that Thailand’s establishment has almost never experienced success in consolidating power through elections. That failure underpins the persistent deficiency of stability in Thai politics and the frequency of its oscillations between different political systems. Traditional elites are undoubtedly experts and are skilful in staging coups to overthrow democratic systems, but they have been unable to maintain durable, long-term power through electoral mechanisms. This distinguishes Thailand from the political history of neighbouring countries—including Indonesia during the Suharto era, Malaysia prior to the 2018 elections and contemporary Singapore—where elites have experienced some success in controlling and/or co-opting elections and relying on them as a tool to confer legitimacy on authoritarianism.

Election results displayed in Bangkok, 24 December 2007. Photo: (SAEED KHAN/AFP/Getty Images)

Thai-style authoritarianism: successful coups, failed elections

The question is: why do Thailand’s traditional elites consistently fail in elections? This question has never been seriously studied, but I propose three preliminary explanations.

First, Thai elites have grown to depend disproportionately on coups as a political tool. In developing expertise in staging coups, they have neglected to accumulate experience and skill in managing power through other methods, as well as under democratic structures. A preference for coup-making has left elites inexperienced in working the party and electoral system, including in such competencies as developing policy platforms, establishing voter bases, building grassroots networks, and even in embedding the state in ordinary civilian life in order to control political thought and behaviour.

The second explanation for traditional elite failure in elections is related to this over-reliance on coup-making: Thailand’s conservative elites have never built up the foundations for a strong or even “real” political party. By real, I refer to a party as an institution with a working organisational structure, that produces policies, espouses ideology, and whose operations are visible in the lives of civilians. Political parties that have been historically established by Thai conservative elites are not comparable to the Golkar party established by Indonesia’s military, or the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) and the People’s Action Party (PAP) established by Malaysian and Singaporean elites respectively. In the absence of their own competitive political parties, Thailand’s traditional elites have historically attempted to control elections through two methods. The first method is flagrant interference and distortion of the electoral process, such as in Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhram’s electoral fraud in 1957. The second method is a reliance on proxy political parties, whereby the military has requested or pressured civilian politicians to collaborate in the establishment of “nominee” political parties in the style of the Justice Unity Party that ran in the elections of 1992.

The third explanation for the historical failings of Thai conservative elites at the polling booth is their absence of unity. If we examine political history from 1957 onwards, palace institutions, the military, the civilian bureaucracy and leading capitalists have built ever-shifting alliances and co-existed in constantly changing relationships of dominance and subordination. For the most part, alliances have emerged as ad-hoc arrangements, in response to urgent challenges to the status quo: the communist threat under the Sarit regime, the growth in political power of economic elites and provincial politicians during the government of Prem Tinsulanonda and, most recently, the challenge posed by the expansion of a mass, grassroots political movement that formed the voting base of political parties aligned with Thaksin.

In the lead up to the next round of elections, the NCPO has certainly attempted to implement several novel measures. These include staying in office for a longer interim than preceding juntas, a new electoral system that will reduce the seats controlled by large political parties, and the installation of a legally-binding 20-year strategic plan (and the list goes on). Fundamentally, however, the NCPO has chosen the same strategy of securing power through elections as the past juntas described above. Unsurprisingly, the NCPO is relying on the co-optation of provincial bosses with local influence (chao pho), as well as politicians formerly aligned with the Thaksin network, to establish an ad-hoc nominee political party, Phalang Pracharat. Also unsurprisingly, the junta is interfering in an electoral process already designed to maintain its rule, whether it be through the co-optation of the Election Commission or gerrymandering to the benefit of Phalang Pracharat. Phalang Pracharat has managed to pull into its orbit politicians with genuine personal popularity from several parties, and the parties’ leaders have publicly anticipated that it will win 150 seats.

150 seats—itself a generous prediction—is, however, far from what is required to establish a single-party government. Phalang Pracharat is unlikely to be spared from the necessity of establishing a coalition constituted by several parties. Though the appointed 250-seat senate will assist in voting in General Prayuth as prime minister, Prayuth will need to control more than 50% of seats (250 MPs) in the legislature to govern securely and guarantee the passage of legislation. Parliamentary politics will once again be replete with lively bargaining, lobbying and money politics, which will form the foundation of a clientelistic relationship between the military and the politicians who govern in Prayuth’s name. Money politics will also confer political influence upon those economic elites who have gained enormous benefits under the current junta and who will play a crucial role in supporting the post-election government.

History shows us that the coalition government likely to emerge from the elections will have a short life span, unlikely to see through a full term. That instability will be resolved by one of two paths: a coup by the military against its own government, or the emergence of extra-parliamentary protest.

Of course, the results of the coming elections cannot be predicted with certainty. It has been a long time since Thailand has had elections at all, and the new mixed-member apportionment electoral system set out in the constitution has never been tested out. On top of all this, a number of new political parties have entered the fray. A new electoral system and regulations, and a changing political landscape, mean that nobody can firmly predict how voters will decide next year.

What, however, will transpire if voter behaviour mirrors the elections held during 2001–11, when voters largely cast their ballots on the basis of parties rather than individuals (as in 2007, for instance, when many candidates who defected from Thai Rak Thai did not win seats)? The NCPO’s strategy to uphold power through elections will fail, because Phalang Pracharat will not receive as many votes as it presently anticipates. Thai politics will see a repeat of the 2007 elections and the “wasted coup”. But if voter behaviour shifts from an emphasis on parties to individuals, Phalang Pracharat stands a chance of receiving more seats—though still not so many that the NCPO will be able to inherit power smoothly.

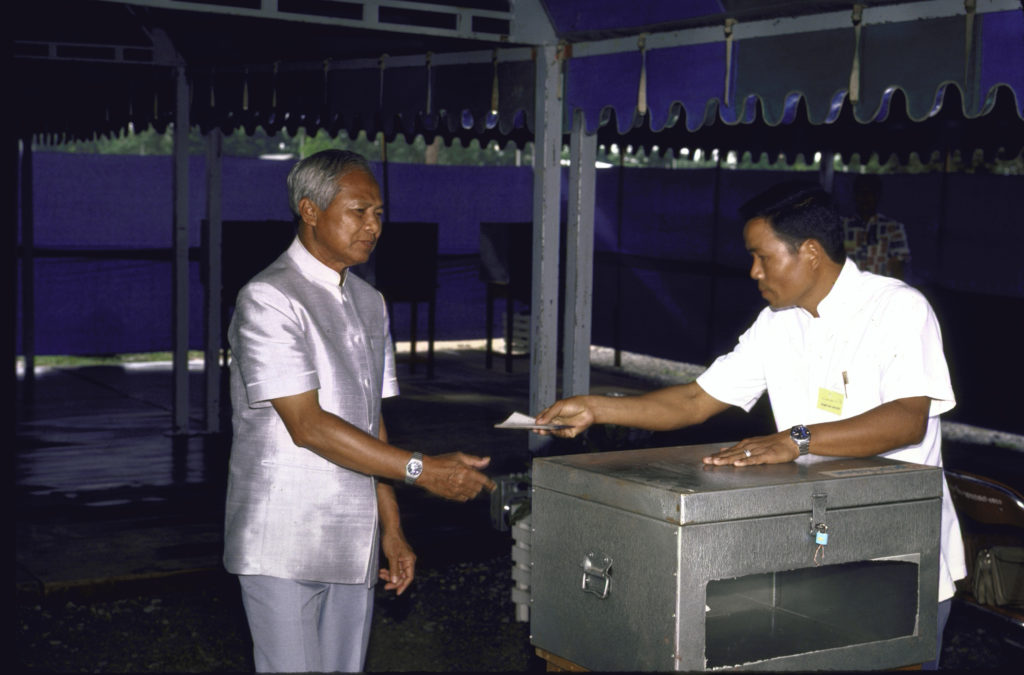

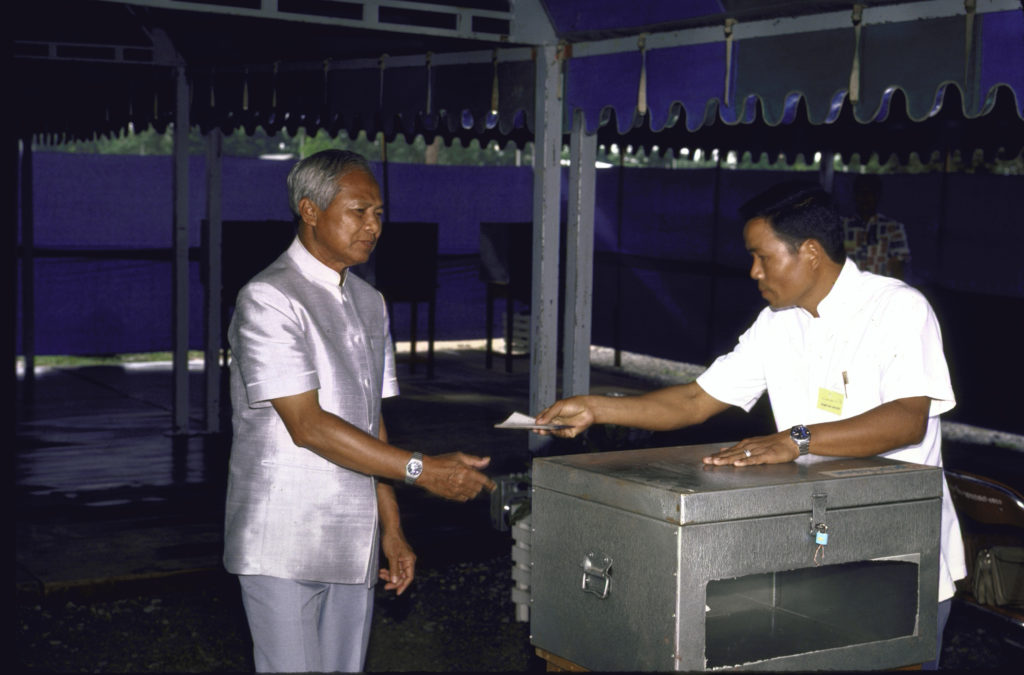

Prime Minister Prem Tinsulanonda (L), during the Parliamentary Elections. (Photo: Robert Nickelsberg/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images)

Not a return to semi-democracy

Several analysts have staked predictions that, in the aftermath of the 2019 elections, Thailand will return to a regime of “semi-democracy” similar to that during the premiership of Prem Tinsulanonda during 1980–88. But those predictions are out of sync with Thailand’s contemporary political context.

“Premocracy” as a regime had compromise or power-sharing between the military and political parties as its foundations. The military did not establish a political party to compete in elections. Nor did it interfere in the electoral process. Albeit within the parameters of an appointed senate and an unelected prime minister, the military allowed parliamentary process to proceed as usual. The NCPO is not restraining itself in the same way. Semi-democracy enjoyed relative stability for 8 years, because it was sustained by charismatic, senior military officials such as General Prem, who were able to mediate between palace institutions, the military, political parties and leading capitalists. All of the above took place in a context where mass civilian political movements had yet to mature, and large political parties had yet to emerge.

These conditions, which sustained semi-democracy under Prem’s leadership, no longer exist today. The NCPO lacks leaders with the charisma to secure compromise between competing political forces; nor does it control a large political party able to secure a convincing majority in the legislature. On top of this, the military presently operates during the transitional period of royal succession, led by General Apirat Kongsompong, who increasingly exhibits distance from the NCPO. Thai politics remains deeply divided between two poles—unripe conditions for a semi-democratic system reliant on power-sharing and compromise.

Thailand Unsettled #1: The Military (with Puangthong Pawakapan)

In the first episode of Thailand Unsettled, Puangthong Pawakapan tackles the theme of "the military", narrowing in on the Internal Security Operations Command

Comparatively speaking, post-election Thai politics will not proceed down the path of the “Malaysia model”, where a strong coalition of opposition parties succeeded in unseating a government that had been in power for decades. But nor will Thailand go down the path of the “Cambodia model”, where the Hun Sen government aggressively interfered in electoral processes to suppress opposition parties and drew upon all manner of measures to ensure that elections were free of competition. Cambodia’s regime can now be classified as a form of electoral authoritarianism, whereby Hun Sen’s Cambodian People’s Party is guaranteed to win elections.

As for Thailand, its elections in 2019 will fall in-between the Malaysian and Cambodia model. Under the “Thailand model”, elections are only the beginning of a new round of struggles to set the terms of a political order that has yet to settle. It will be difficult for the NCPO to establish a robust authoritarian regime, but nor will Thailand transition to a stable, democratic system.

บทนำ

การเลือกตั้งของไทยที่กำลังจะมีขึ้นในวันที่ 24 กุมภาพันธ์ (หากไม่มีการเลื่อนการเลือกตั้งอีก) จะเป็นการเลือกตั้งครั้งแรกของประเทศหลังจากที่มีการรัฐประหาร 22 พฤษภาคม 2557 โดยคณะรักษาความสงบแห่งชาติ (คสช.) ที่นำโดยพล.อ.ประยุทธ์ จันทร์โอชา การเลือกตั้งครั้งนี้มีเดิมพันที่ค่อนข้างสูงไม่เพียงต่อฝ่ายรัฐบาลทหารที่ครองอำนาจและพรรคการเมืองต่างๆ เท่านั้น หากยังมีเดิมพันเกี่ยวกับรูปแบบของระบอบการเมืองไทยและทิศทางของประชาธิปไตยไทยในช่วงเปลี่ยนผ่านด้วย ทั้งนี้ ฝ่ายชนชั้นนำของไทย (establishment) ที่ยึดกุมอำนาจอยู่ในปัจจุบันต้องการสถาปนาระเบียบทางการเมืองแบบใหม่ที่มีลักษณะของระบอบอำนาจนิยมครึ่งใบ (semi-authoritarianism) เพื่อควบคุมอำนาจและการจัดสรรผลประโยชน์และความมั่งคั่งในหมู่ชนชั้นนำ โดยมองว่าการจัดการเลือกตั้งจะช่วยผ่อนคลายความอึดอัดทางการเมืองภายในประเทศ และช่วยทำให้ชนชั้นนำครองอำนาจได้อย่างชอบธรรม (ในสายตาของชุมชนนานาชาติ) มากกว่าสภาพที่เป็นอยู่ในปัจจุบัน อย่างไรก็ตาม ด้วยปัจจัยหลายประการ บทวิเคราะห์สั้นๆ นี้จะชี้ให้เห็นว่าความพยายามสถาปนาระบอบการเมืองแบบใหม่นี้ยากที่จะราบรื่นและสำเร็จได้โดยง่าย การเมืองไทยหลังการเลือกตั้งจะก้าวเข้าสู่สภาวะตึงเครียดและสภาพที่อำนาจแตกออกเป็นหลายเสี่ยง (fragmented power)

การเลือกตั้ง 2562 มีความสำคัญทางประวัติศาสตร์ เพื่อที่จะเข้าใจสถานะของการเลือกตั้งครั้งนี้ ต้องให้ความสำคัญกับบริบทพิเศษของการจัดการเลือกตั้ง กล่าวคือ มันเป็นเลือกตั้งที่จะเกิดขึ้นภายใต้สภาวะที่คณะรัฐประหารยังถือครองอำนาจอย่างเด็ดขาด ย้อนไปในประวัติศาสตร์การเมืองไทยสมัยใหม่ตั้งแต่ปี 2500 เป็นต้นมา เคยมีการจัดการเลือกตั้งภายใต้รัฐบาลรัฐประหารมาแล้ว 3 ครั้งคือ การเลือกตั้งปี 2512 ในสมัยจอมพลถนอม กิตติขจร, การเลือกตั้ง 2535 ภายใต้รัฐบาลของอานันท์ ปันยารชุน ที่ได้รับแต่งตั้งเป็นายกรัฐมนตรีหลังการรัฐประหารปี 2534 ของคณะรักษาความสงบเรียบร้อยแห่งชาติ (รสช.), และการเลือกตั้งปี 2550 ภายใต้รัฐบาลของ พล.อ. สุรยุทธ์ จุลานนท์ ที่ขึ้นสู่อำนาจหลังการรัฐประหารโค่นล้มอำนาจของรัฐบาลทักษิณ ชินวัตร ในปี 2549

การเลือกตั้งภายใต้คณะรัฐประหาร: บทเรียนจากประวัติศาสตร์

การเลือกตั้งภายใต้คณะรัฐประหารทั้ง 3 ครั้ง เกือบทั้งหมดนำไปสู่ความไร้เสถียรภาพทางการเมืองและวิกฤต เริ่มจากการเลือกตั้งปี 2512 แม้ว่าพรรคสหประชาไทย ซึ่งเป็นพรรคของทหารจะชนะเลือกตั้งมาเป็นอันดับ 1 แต่ได้ที่นั่งไม่มากพอที่จะจัดตั้งรัฐบาล จึงต้องจัดตั้งรัฐบาลผสมที่ประกอบด้วยพรรคการเมืองขนาดเล็กบวกกับส.ส.อิสระที่ไม่สังกัดพรรค ในขณะที่พรรคประชาธิปัตย์เป็นแกนนำพรรคฝ่ายค้านที่มีความเข้มแข็ง ผลลัพธ์ก็คือ จอมพลถนอม ผู้ผันตัวจากนายกฯ ของคณะรัฐประหารมาเป็นนายกฯ จากการเลือกตั้งไม่สามารถคุมเสียงในสภาได้อย่างมีเอกภาพ และไม่คุ้นกับการต้องต่อรองกับพรรคการเมืองในสภาโดยไม่มีอำนาจสั่งการเด็ดขาดเหมือนสมัยเป็นนายกฯ จากการยึดอำนาจ ในที่สุดจึงทำการรัฐประหารตัวเองในปี 2514 ยกเลิกรัฐธรรมนูญและพรรคการเมือง และกลับไปปกครองแบบเผด็จการเบ็ดเสร็จเช่นเดิม แต่แทนที่ทำเช่นนี้แล้วทุกอย่างจะสงบราบรื่น กลับสร้างความอึดอัดผิดหวังให้กับประชาชน และการรัฐประหารตนเองกลายเป็นชนวนไปสู่การลุกฮือของประชาชนในเหตุการณ์ 14 ตุลาฯ 2516 โค่นล้มระบอบเผด็จการกองทัพของจอมพลถนอมจนต้องลงจากอำนาจ

ในทำนองเดียวกัน การเลือกตั้งปี 2534 แม้ว่าพรรคสามัคคีธรรมซึ่งเป็นพรรคตัวแทนของกองทัพ ที่รวบรวมผู้สมัครมาจากบรรดาเจ้าพ่อผู้มีอิทธิพลในจังหวัดต่างๆ จะชนะการเลือกตั้ง แต่ก็ได้เสียงไม่ถึงครึ่งหนึ่ง ทำให้ต้องจัดตั้งรัฐบาลผสม และเมื่อพล.อ.สุจินดา คราประยูร ผู้นำรัฐประหารขึ้นมาสู่อำนาจ ก็ถูกประท้วงต่อต้านจากประชาชน จนเกิดเป็นเหตุการณ์ “พฤษภาคม 2535” ซึ่งรัฐบาลของสุจินดาปราบปรามประชาชนแต่ก็ต้องลงจากอำนาจไปในท้ายที่สุด สำหรับการเลือกตั้งปี 2550 นั้น ฝ่ายผู้นำคณะรัฐประหารดำเนินยุทธศาสตร์ที่เปลี่ยนไปบ้างจากเดิม คือ เปลี่ยนระบบเลือกตั้ง ยุบพรรคขนาดใหญ่ของทักษิณ และบีบให้มุ้งต่างๆ ในพรรคของทักษิณแยกตัวออกไปตั้งพรรคการเมืองใหม่ๆ โดยที่คณะรัฐประหารสนับสนุนพรรคการเมืองเหล่านั้นอยู่เบื้องหลัง โดยหวังว่ายุทธศาสตร์ดังกล่าวจะทำให้พรรคการเมืองที่นำโดยทักษิณ ชินวัตร พ่ายแพ้ในการเลือกตั้ง แต่ผลการเลือกตั้งออกมาในทิศทางตรงกันข้าม เนื่องจากพรรคพลังประชาชนของฝ่ายทักษิณยังคงชนะเลือกตั้งมาเป็นอันดับ 1 ด้วยเสียงจำนวนมาก ในขณะที่พรรคที่คณะรัฐประหารสนับสนุนได้ที่นั่งต่ำกว่าที่คาดคิดมาก จึงทำให้ฝ่ายชนชั้นนำไม่สามารถสืบทอดอำนาจผ่านการเลือกตั้งตามยุทธศาสตร์ที่วางไว้ การรัฐประหารดังกล่าวถูกเรียกขานว่าเป็น “การรัฐประหารที่เสียของ” และกลายเป็นจุดเริ่มต้นของสงครามการเมืองเสื้อสีและความขัดแย้งบนท้องถนนยืดเยื้อยาวนานและเต็มไปด้วยความรุนแรง

สรุปก็คือ ชนชั้นนำเก่าของไทยแทบไม่ประสบความสำเร็จในการครองอำนาจและสืบทอดอำนาจผ่านสถาบันการเลือกตั้ง และด้วยความล้มเหลวนี้ทำให้การเมืองไทยจึงไร้เสถียรภาพมากและมีการเปลี่ยนระบอบการเมืองกลับไปกลับมาค่อนข้างถี่ เนื่องจากชนชั้นนำเชี่ยวชาญและมีทักษะในการทำรัฐประหารล้มระบอบการเมืองที่มาจากการเลือกตั้ง แต่เมื่อพยายามจะครองอำนาจต่อเนื่องยาวนานผ่านกระบวนการเลือกตั้งกลับไม่สามารถทำได้ ซึ่งแตกต่างจากประเทศเพื่อนบ้านอย่างอินโดนีเซียในยุคซูฮาร์โต มาเลเซีย (ก่อนหน้าการเลือกตั้งปี 2018) และสิงคโปร์ ที่ชนชั้นนำสามารถควบคุมการเลือกตั้งและอาศัยการเลือกตั้งมาเป็นเครื่องมือสร้างความชอบธรรมให้กับระบอบอำนาจนิยมของตน

Election results displayed in Bangkok, 24 December 2007. Photo: (SAEED KHAN/AFP/Getty Images)

ระบอบอำนาจนิยมแบบไทย: รัฐประหารสำเร็จ เลือกตั้งล้มเหลว

คำถามคือ เหตุใดชนชั้นนำเก่าของไทยจึงล้มเหลวในการเมืองเรื่องการเลือกตั้ง ประเด็นนี้ยังไม่มีความพยายามศึกษาวิเคราะห์อย่างจริงจัง แต่บทความนี้อยากจะทดลองเสนอบทวิเคราะห์ว่า มีคำอธิบายอย่างน้อย 3 ประการ หนึ่ง ชนชั้นนำไทยที่มีกองทัพเป็นเครืองมือสำคัญพึ่งพิงการรัฐประหารมากเกินไปในฐานะเครื่องมือทางอำนาจตลอดมาในประวัติศาสตร์ เมื่อพัฒนาและเครื่องมือนี้อย่างเชี่ยวชาญ จึงไม่พัฒนาและสั่งสมทักษะในการครองอำนาจผ่านวิถีทางอื่นๆ ภายใต้กติกาประชาธิปไตย จึงทำให้ไม่มีประสบการณ์ในการเมืองระบบพรรคและการเมืองแบบการเลือกตั้ง ซึ่งต้องอาศัยความสามารถในการสร้างชุดนโยบาย สร้างฐานคะแนนเสียง สร้างเครือข่ายทางการเมืองในพื้นที่ลึกลงไปถึงระดับชุมชน หรือกระทั่งความสามารถในการแทรกซึมกลไกรัฐลงไปในสังคมเพื่อควบคุมความคิดและพฤติกรรมทางการเมืองของประชาชน

นำไปสู่คำอธิบายที่สองซึ่งเกี่ยวเนื่องกันคือ ชนชั้นนำอนุรักษ์นิยมไทยจึงไม่เคยพัฒนาพรรคการเมืองที่เข้มแข็งของตนเอง ที่มีความเป็นสถาบันการเมืองแบบพรรคการเมืองจริงๆ ที่ประกอบไปด้วยการจัดองค์กรที่ดี การผลิตนโยบายและสร้างอุดมการณ์แห่งรัฐ และการเข้าถึงประชาชนอย่างใกล้ชิด แบบเดียวกับที่กองทัพอินโดนีเซียสร้างพรรคโกลคาร์ (Golkar) หรือชนชั้นนำในมาเลเซียและสิงคโปร์สร้างพรรคอัมโน (UMNO) และพรรคกิจประชา (PAP: People’s Action Party) ตามลำดับ ปราศจากพรรคการเมืองที่จัดตั้งอย่างเข้มแข็งและเป็นตันแทนของชนชั้นนำ ชนชั้นนำเก่าและกองทัพพยายามควบคุมการเลือกตั้งโดยทำแค่สองอย่างคือ หนึ่ง แทรกแซงและบิดเบือนกระบวนการเลือกตั้งโดยใช้อำนาจรัฐแบบโจ่งแจ้ง เช่น โมเดลการเลือกตั้งสกปรกปี 2500 สมัยจอมพล ป. หรือการเลือกตั้งปี 2512 สมัยจอมพลถนอม และสอง การพึ่งพิงพรรคการเมืองของนักการเมือง หรือไปขอและบังคับให้นักการเมืองมาช่วยจัดตั้งพรรคให้ตนเองในลักษณะพรรคนอมินีแบบพรรคสามัคคีธรรมในการเลือกตั้ง 2535 และมุ้งการเมืองของอดีตพรรคไทยรักไทยในการเลือกตั้ง 2550 ซึ่งมีจุดอ่อนตรงที่ทำให้คณะรัฐประหารขาดอำนาจเด็ดขาดในรัฐสภา

สาม ชนชั้นนำอนุรักษ์นิยมของไทยขาดความเป็นเอกภาพ สถาบันประเพณี กองทัพ ราชการพลเรือน และกลุ่มทุนขนาดใหญ่มีการสร้างพันธมิตรและปรับเปลี่ยนความสัมพันธ์ทางอำนาจอยู่เสมอในแต่ละช่วงทางประวัติศาสตร์ หากพิจารณาตั้งแต่หลังทศวรรษ 2500 เราเห็นการปรับเปลี่ยนความสัมพันธ์หลายครั้ง สภาพเช่นนี้ ทำให้ชนชั้นนำขาดยุทธศาสตร์ทางการเมืองที่เป็นเอกภาพในระยะยาว ระบอบการเมืองที่ชนชั้นนำสถาปนาขึ้นส่วนใหญ่ถูกสร้างขึ้นเพื่อตอบความท้าทายและภัยคุกคามการเมืองเฉพาะหน้าเป็นหลัก ไล่มาตั้งแต่ภัยคุกคามคอมมิวนิสต์ในยุคระบอบสฤษดิ์ ความท้าทายจากการเติบโตของพลังนอกระบบราชการโดยเฉพาะนายทุนและนักการเมืองต่างจังหวัดในสมัยรัฐบาลเปรม และความท้าทายจากการเติบโตของขบวนการมวลชนรากหญ้าที่เป็นฐานเสียงของพรรคการเมืองขนาดใหญ่ภายใต้เครือข่ายทักษิณในยุคปัจจุบัน

Thailand Unsettled #1: The Military (with Puangthong Pawakapan)

In the first episode of Thailand Unsettled, Puangthong Pawakapan tackles the theme of "the military", narrowing in on the Internal Security Operations Command

ทั้งนี้ผลการเลือกตั้งยังมีความไม่แน่นอน เนื่องจากประเทศไทยว่างเว้นจากการเลือกตั้งไปนาน มีการใช้ระบบเลือกตั้งแบบใหม่ที่ไม่มีใครคุ้นเคยเป็นครั้งแรกในประวัติศาสตร์ และยังมีพรรคการเมืองใหม่ๆ เกิดขึ้นหลายพรรคในการเลือกตั้งครั้งนี้ กติกาและภูมิทัศน์การเมืองที่เปลี่ยนไปนี้ ทำให้ไม่มีใครทราบว่าพฤติกรรมการเลือกตั้งจะเปลี่ยนไปเช่นไร หากพฤติกรรมการเลือกตั้งของผู้เลือกตั้งส่วนใหญ่ยังเหมือนเดิมในช่วงปี 2544-2554 ที่เลือกพรรคการเมืองมากกว่าตัวบุคคล และเน้นเลือกพรรคขนาดใหญ่ (ดังที่พบในปี 2550 ว่าผู้สมัครจำนวนมากที่ย้ายออกจากพรรคไทยรักไทยสอบตก) แผนการทางการเมืองของคสช.ก็จะล้มเหลวเนื่องจากพรรคพลังประชารัฐจะไม่ได้เสียงมากอย่างที่คาดหวังไว้ การเมืองไทยก็จะย้อนกลับไปสู่ช่วงปี 2550 แต่หากพฤติกรรมผู้เลือกตั้งเปลี่ยน โดยประชาชนหันไปเลือกตัวบุคคล พรรคพลังประชารัฐก็จะมีโอกาสได้ที่นั่งมากขึ้น แต่ก็ไม่มากพอที่จะทำให้การสืดทอดอำนาจของคสช. เป็นไปอย่างราบรื่น

Prime Minister Prem Tinsulanonda (L), during the 1986 parliamentary Elections. (Photo: Robert Nickelsberg/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images)

มิได้กลับสู่ประชาธิปไตยครึ่งใบ

นักวิเคราะห์หลายคนมักจะคาดการณ์ว่าการเมืองไทยหลังการเลือกตั้งปี 2562 จะย้อนกลับไปสู่ระบอบ “ประชาธิปไตยครึ่งใบ” (semi-democracy) แบบสมัยพลเอกเปรม ติณสูลานนท์ ซึ่งเป็นการคาดการณ์ที่ไม่สอดคล้องกับบริบท ระบอบการเมืองแบบเปรมวางอยู่บนฐานของการประนีประนอมระหว่างกองทัพกับพรรคการเมือง โดยกองทัพไม่จัดตั้งพรรคลงไปแข่งขันในระบบ ไม่แทรกแซงกระบวนการเลือกตั้ง และยอมรับให้ประชาธิปไตยแบบรัฐสภาทำงานไปตามปกติ ซึ่งแตกต่างจากสิ่งที่คสช.ทำ นอกจากนั้นระบอบประชาธิปไตยครึ่งใบมีเสถียรภาพพอสมควรในเวลา 8 ปี เพราะอาศัยผู้นำกองทัพที่มีบารมีอย่างพลเอกเปรมที่สามารถประสานระหว่างสถาบันประเพณี กองทัพ พรรคการเมือง และกลุ่มทุน (รวมทั้งตัวละครภายนอกอย่างสหรัฐอเมริกา) ในบริบทที่ขบวนการประชาชนนอกรัฐสภายังไม่เติบโตและพรรคการเมืองขนาดใหญ่ยังไม่เกิดขึ้น ปัจจัยที่ค้ำจุนระบอบประชาธิปไตยครึ่งใบแบบสมัยเปรมมิได้ดำรงอยู่แล้วในปัจจุบัน และโมเดลทางการเมืองของคสช.มิใช่ระบอบ “เปรมาธิปไตย” (Premocracy) ความพยายามทางการเมืองของคสช. คือ การสถาปนาระบอบเผด็จการครึ่งใบที่กองทัพทั้งควบคุมและเข้าไปแทรกแซงระบบพรรคการเมืองและรัฐสภา โดยจัดตั้งพรรคการเมือง มีกรรมการยุทธศาสตร์แห่งชาติควบคุม และองค์กรอิสระที่มาจากการสรรหาแต่งตั้ง (ในสมัยคสช.ได้ทำการตั้งคณะกรรมการองค์กรอิสระใหม่เกือบทุกองค์กร)

อย่างไรก็ตาม การที่คสช.ปราศจากผู้นำที่มีบารมีที่ได้รับการยอมรับจากทุกฝ่าย บวกกับการไม่มีพรรคการเมืองขนาดใหญ่ที่สามารถชนะเสียงข้างมากแบบเด็ดขาด บวกกับบทบาทของกองทัพในยุค “เปลี่ยนผ่าน” ภายใต้การนำของพล.อ.อภิรัชต์ คงสมพงษ์ ที่มีลักษณะเป็นอิสระมากขึ้นจากคสช. บวกกับสภาวะการเมืองที่ยังแตกแยกเป็นสองขั้วอย่างลึกซึ้ง ทำให้การสถาปนาระบอบเผด็จการครึ่งใบยากที่จะบรรลุผลอย่างราบรื่น ในทางตรงกันข้ามมันจะดำเนินไปอย่างขลุกขลักทุลักทุเล

กล่าวในมุมเปรียบเทียบ การเมืองไทยหลังการเลือกตั้ง จะมิได้ดำเนินไปแบบ “มาเลเซียโมเดล” ที่พรรคฝ่ายค้านสามารถรวมพลังกันอย่างเข้มแข็งและโค่นล้มแนวร่วมฝ่ายรัฐบาลที่นำโดยพรรคอัมโนที่ครองอำนาจมายาวนานหลายทศวรรษ และเริ่มต้นกระบวนการพัฒนาประชาธิปไตยและการปรับโครงสร้างอำนาจทางการเมือง ในขณธเดียวกันมันจะไม่ได้เป็นแบบ “กัมพูชาโมเดล” ที่พรรคฝ่ายรัฐบาลของนายกฯ ฮุน เซน ที่ใช้อำนาจรัฐอย่างเข้มข้นแทรกแซงกระบวนการเลือกตั้งและขจัดคู่แข่งทางการเมืองโดยใช้มาตรการทุกวิถีทางจนการเลือกตั้งปราศจากการแข่งขัน และทำให้พรรคประชาชนกัมพูชาของเขาชนะการเลือกตั้งแบบเด็ดขาด กลายเป็นระบอบอำนาจนิยมที่มาจากการเลือกตั้ง (electoral authoritarianism) สำหรับการเลือกตั้ง 2562 ของไทย จะมีลักษณะที่อยู่ตรงกลางระหว่างมาเลเซียและกัมพูชาโมเดล ทั้งนี้ “โมเดลแบบไทย” การเลือกตั้งเป็นเพียงจุดเริ่มต้นของความขัดแย้งรอบใหม่ของการค้นหาระเบียบทางการเมืองใหม่ที่ยังไม่ลงตัว โดยระบอบอำนาจนิยมที่เข้มแข็งยากที่จะถูกสถาปนาขึ้นมา แต่การเปลี่ยนผ่านไปสู่ระบอบประชาธิปไตยที่มีเสถียรภาพก็จะยังไม่เกิดขึ้นเช่นกัน

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss