Indonesia’s Banten Bay, 80 kilometres west of Java, is the final resting place for Australian warship HMAS Perth (I) and its eternal companion, USS Houston, both destroyed within minutes of each other in the early hours of 1 March 1942. Having served three years in the Royal Australian Navy (1939–1942), Perth has now spent some 80 years in the watery depths of Banten Bay. While the 80th anniversary of Perth’s loss is a significant one for survivors and descendants, it also represents an opportune moment to reflect on this wreck’s legacy and how it has changed over the decades in both Australia and Indonesia. One notable aspect of this changing legacy is the growing interest among Indonesians in learning more about Perth, better understanding its historical significance, and developing an appreciation of why Australians care so much about it.

Wreath laying during the 76th anniversary commemorations above the wreck site in Banten Bay, 28 February 2018. Credit: George Hatfield (reproduced with permission).

Both Perth and Houston had fought and survived the Battle of the Java Sea, and were attempting to flee through the Sunda Strait to the relative safety of Java’s south coast when they encountered the Japanese Western Invasion Fleet, arriving under cover of darkness. Perth was low on fuel and ammunition, its crew already spent after being at action stations for days. When the gunners ran out of ammunition, they fired star shells – explosives for illumination – until the order came to abandon ship. Perth went down shortly after midnight, and Houston followed less than an hour later. More than 1000 men died that night, 353 of them from Perth, with most of the survivors taken as prisoners of war.

Perth and Houston were in the Java Sea to defend Dutch colonial interests in the then-Netherlands East Indies. These efforts were intended to stop – or at least delay – the arrival of Japanese forces in Java. For many years, Perth’s legacy was defined by its contribution to the Allied war effort, and by the terrible odds its crew had faced in their final days at sea. Although not successful in their final mission, it remained a point of pride among Perth survivors that, despite being desperately outnumbered, they had never surrendered.

In recent years, Perth’s legacy has evolved. The evolution has been fraught at times, its nadir marked by the discovery in 2017 that Perth had been salvaged on an industrial scale, with no regard for the presence of human remains or the memory of those lost. Compounding the grief of survivors and descendants was the knowledge that authorities had first been alerted to suspicious salvaging activity on the wreck in 2013. But Australia had neglected Perth, and the need to proactively engage Indonesia around this shared heritage, for decades. Indeed, despite there being a number of Australian warships outside Australian waters, and with the exception of HMAS AE1 in Papua New Guinea and HMAS AE2 in Turkey, Australia has not proactively engaged any other state on the matter of wartime underwater heritage. The bilateral relationship was, furthermore, at a low point, making a rapid response even more difficult.

By 2015, Australian and Indonesian government departments and agencies had signed a Memorandum of Understanding that allowed them to engage for the purposes of collaboration in research in maritime archaeology and underwater cultural heritage management. This allowed for researchers to survey the site, first with a multi-beam sonar in 2016, and then via a joint dive by archaeologists from the Australian National Maritime Museum and the National Research Centre for Archaeology (ARKENAS) in 2017. These surveys established the full extent of the destruction, most of which had taken place since 2013.

Indonesian maritime archaeologist Shinatria Adhityatama surveys HMAS Perth (I) during the joint site survey by Arkenas and the ANMM, May 2017. Credit: Australian National Maritime Museum / National Research Centre for Archaeology (reproduced with permission).

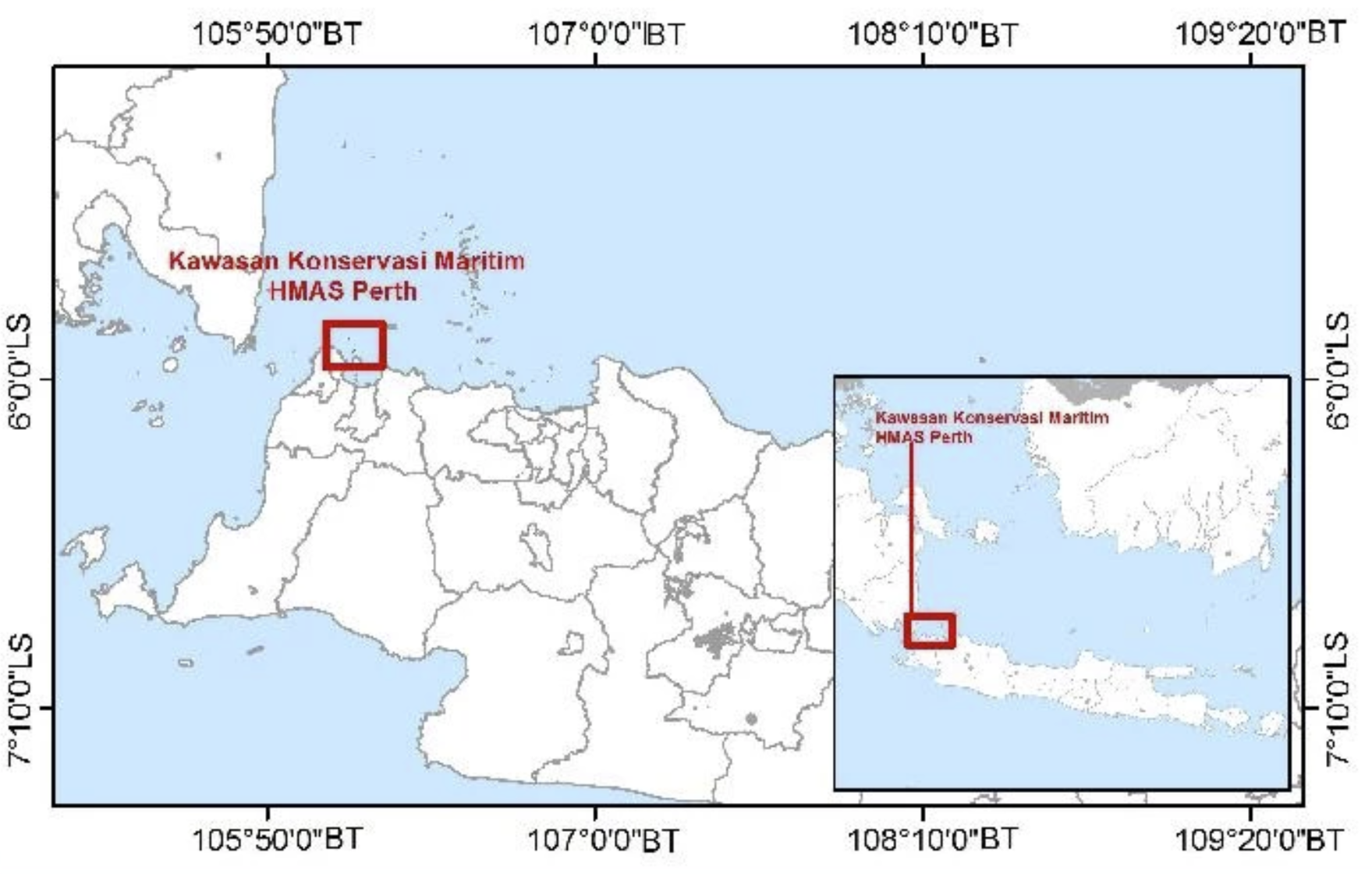

Rather than derailing the tentative steps towards better bilateral engagement on maritime heritage, the survey results had a galvanising effect for both Australia and Indonesia, in the process creating a new legacy for Perth. In 2018, on the symbolic date of 28 February, Perth was inscribed as a Maritime Conservation Zone by Indonesia’s Minister of Marine Affairs and Fisheries– the nation’s first such zone. The designation provides a legal basis for the ongoing protection and care of the site, and represents a major shift in the way both Indonesia and Australia have approached Perth. If the industrial scale salvaging of Perth was the nadir, this was, to date at least, the zenith. Instead of shying away from the complexities and sensitivities of managing an Australian warship in Indonesian waters, as had been the case since 1942, the establishment of the Maritime Conservation Zone was a sign that both countries were committed to ensuring better management outcomes for the wreck into the future—and to doing so together.

Perth and Houston are located in Banten Bay on the western tip of Java. A Maritime Conservation Zone (Kawsasan Konservasi Maritim) was established around Perth in 2018, with Houston expected to be inscribed in the near future. Credit: Copyright: Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries (Indonesia) (reproduced with permission).

The wreck of HMAS Perth (I) lies to the north of Pulau Panjang in Banten Bay. A Maritime Conservation Zone was declared around the wreck in 2018. Credit: Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries (Indonesia) (reproduced with permission).

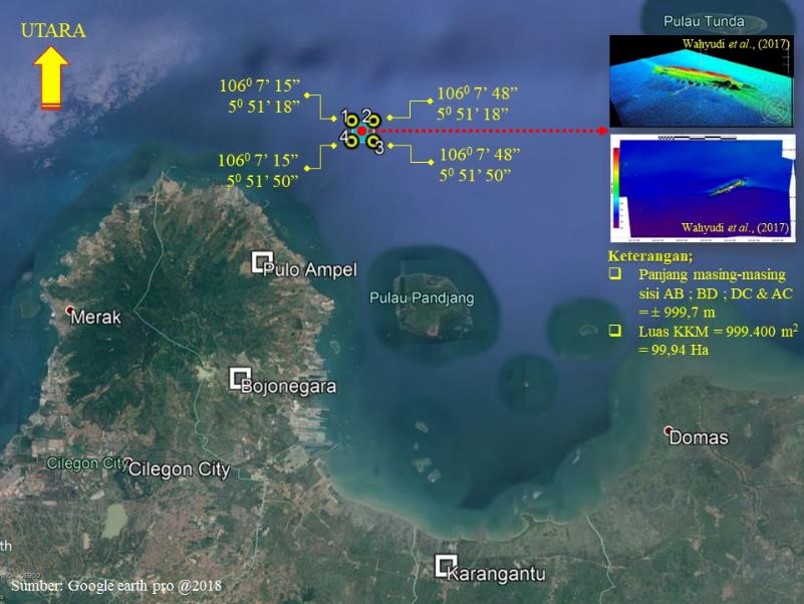

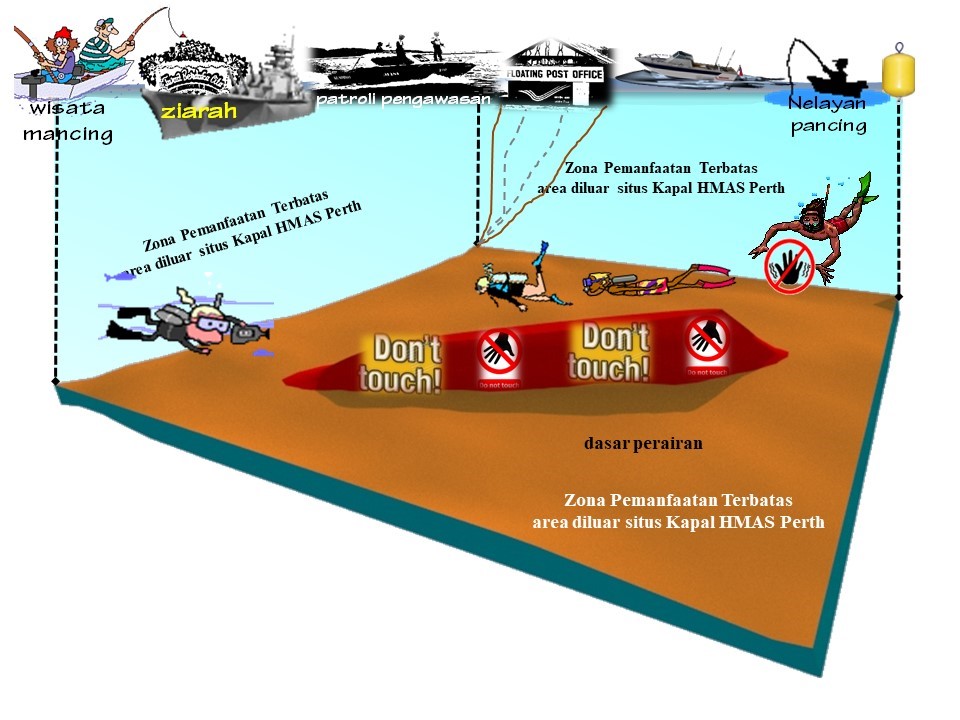

Perth’s Maritime Conservation Zone consists of a core zone and a zone of limited use, with a total area of 99.94 hectares. The core zone is the 9180 m2 area of the wreck itself, which lies approximately 35 metres below sea level. Only limited activities are permitted within the core zone: surveillance patrols, research and non-extractive development, and educational activities. The larger zone of limited use permits a wider range of activities for the benefit of local communities, including pilgrimages or religious ceremonies, water-based tourism, fishing and aquaculture.

The Maritime Conservation Zone declared around Perth in 2018 provides for a core zone, in which activities are strictly limited, and a wider zone of limited utilisation. Credit: Office of Marine Affairs and Fisheries, Banten Province (reproduced with permission).

Notably, Perth was not inscribed as a cultural heritage zone, but as a marine conservation site that brings together both cultural and natural values in the form of the archaeological and historical significance of the wreck, and the marine ecosystem that has developed around it. This designation aims to guarantee the sustainable preservation of the wreck as underwater cultural heritage, to optimise the potential use of the wreck site, and to improve the welfare of the coastal communities in the vicinity of the Zone.

Fish on the wreck of HMAS Perth (I), May 2017. Credit: Australian National Maritime Museum / National Research Centre for Archaeology (reproduced with permission).

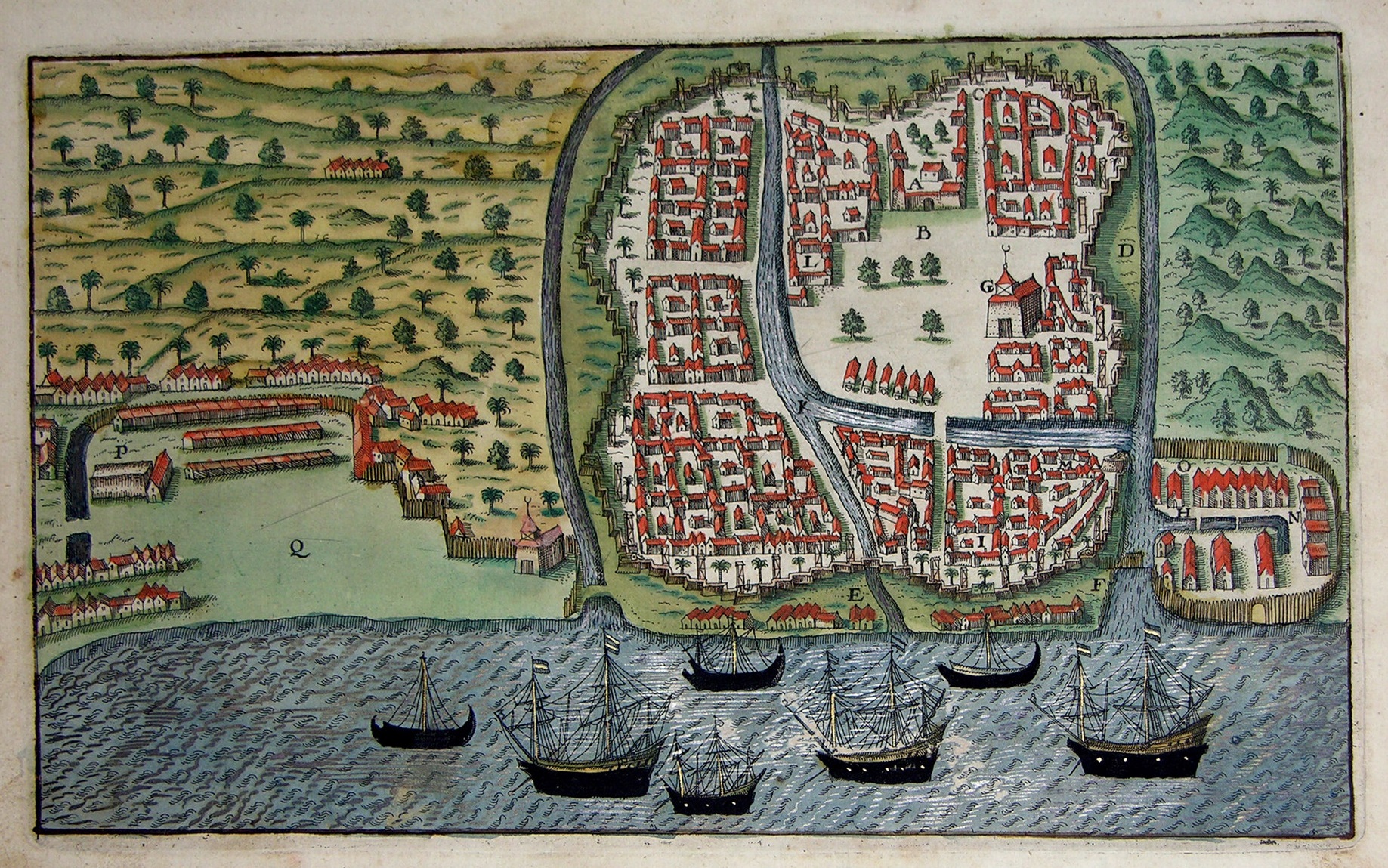

In addition to the legal and administrative changes the Zone’s introduction has prompted, it has also served to broaden Perth’s legacy, expanding it beyond a purely Australian (or even Allied) story and instead also connecting it with Indonesian and Bantenese histories. This is because responsibility for implementing the Maritime Conservation Zone lies not at the national but the provincial level. As such, it is the officials of Banten province who must not only develop a plan to manage Perth for the future but provide the resources – including the funding – to support it. This is a significant responsibility that must be balanced with the needs of the local community in and around Banten Bay. These provisions have served to further expand Perth’s legacy, allowing for clearer links to be drawn with the Japanese occupation, Indonesia’s post-war independence, and the rich maritime history of Banten Bay that dates back centuries. These histories provide valuable context to Perth’s presence in Banten Bay, with implications for how it is managed by provincial authorities for the future.

Bird’s eye view of Banten in 1596 from 1st edition of the De Brys’ Little Voyages (Frankfurt, 1599). Probably based on maps published by Willem Lodewyckszoon. Public Domain on Wikimedia Commons.

In recent weeks, reports have surfaced that Indonesia plans to exploit Perth’s legacy by opening the wreck up to recreational diving. Notably, it was recreational divers who, in 2013, first drew attention to suspicious activity on the wreck. Nevertheless, the reports have met with anger in some circles, with fears that Australia’s war dead will be further disturbed by unregulated recreational diving activities. Dive tourism, were it to go ahead, would be tightly regulated by the provisions of the Maritime Conservation Zone. Perth lies at a depth of 35 metres, and the site is notorious for its turbidity, strong currents and the narrow window of the year in which it is suitable for diving. It is unlikely to attract inexperienced divers. Instead, divers would need to be accompanied by an experienced guide, possibly a local. Their presence would act as a disincentive to recreational divers, as well as larger-scale salvagers, disturbing the wreck. It would also contribute to the creation of vested interest arrangements with locals to protect the site. Without regular divers monitoring and simply being present on the site, the door may be open to further salvaging and destruction.

Pulau Panjang in Indonesia’s Banten Bay. Credit: Research Institute for Coastal Resources and Vulnerability, Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries (Indonesia) (reproduced with permission).

While dive tourism cannot be ruled out, it is more likely that future management plans will emphasise the role of local communities by encouraging them to develop a stronger understanding of how Perth’s presence connects with their own history and future. Promoting fishing and sustainable livelihoods on nearby Pulau Panjang is an obvious example, but there are also tourism opportunities through the development of a site museum or visitor interpretation centre, focusing on Perth and Houston while also contextualising them within Banten Bay’s maritime history. Such a development would attract both domestic and foreign visitors, potentially introducing Perth’s story to an entirely new demographic.

Floating net cages for fishing and aquaculture, including anchovies and lobsters. In addition to being located close to a busy industrial port, the marine space around HMAS Perth (I) and USS Houston is in heavy use by those who make a living from fishing and aquaculture. Credit: Research Institute for Coastal Resources and Vulnerability, Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries (reproduced with permission).

Contrary to suggestions that Indonesia plans to exploit Perth’s legacy, there is in fact a keen interest in Indonesia, and Banten, in learning more about Perth. Last year, tertiary-level students from across Indonesia came together to learn more about Perth within the context of Indonesia’s underwater cultural heritage. This week, Jakarta’s Marine Heritage Gallery will run an awareness raising activity on to commemorate the 80th anniversary and introduce Perth to the next generation of school-aged children.

It is futile to imagine a scenario in which Perth’s destruction was avoided. At the same time, the salvage of Perth offers a salutary lesson in what is needed—proactive engagement, people-to-people connections, a willingness to develop mutual trust and respect—to avoid the destruction of other Australian warships lost outside territorial waters.

Looking forward, engaging local communities is essential if Perth is to be protected for the future. This is not about asking people to police the wrecks on behalf of Australia and the United States of America. Instead, it is about raising awareness of the significance of Perth to Indonesia’s history, and creating opportunities for locals to develop their own relationship with the wreck. Australians care deeply about this wreck and the men who died when it sank; if Indonesians feel the same way, Perth’s chances of future protection and preservation will be doubled.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss