On 4 April, a senior citizen was reported roaming the streets of Guagua, Pampanga amid the enhanced community quarantine. During the lockdown, it was mandatory to wear masks and secure a quarantine pass when going outside. Dressed in a pink housecoat, Lola (Grandmother) Rosa wasn’t wearing any of the required protective gear while she pushed a cart filled with recyclable trash. She was going to sell the trash at a junk shop to earn enough money to buy rice for her family.

Like Lola Rosa, many Filipino grandmothers bear the brunt of providing and caring for their families. Even in old age, they engage in care work or do odd jobs, ensuring family welfare at all costs. During a global pandemic that targets everyone, but most especially the elderly, who will care for lola?

Family dynamics in the Philippines

The Philippines is home to more than 24 million families, almost half of which reside in urban areas. Authority in the family is mostly vested in the parents, with the father traditionally seen as the haligi ng tahanan (the pillar of the family) and the mother as the ilaw ng tahanan (the guiding light of the family). But the popular depiction of the traditional Filipino family as a nuclear unit has not always rung true. Nuclear family units typically stretch to and are closely linked with a larger extended family. Other relatives can exercise influence, especially when able to contribute to such expenses as school fees.

Grandparents play a key role in the Filipino family. This importance is reflected, at least on paper, in the Civil Code of the Philippines which states that, “Grandparents shall be consulted by all members of the family on all important family questions.” Grandparents often play a large role in raising grandchildren, particularly in middle to lower class families. This is widely depicted in teleseryes (Filipino TV dramas), where lolas and lolos from poor families tend to be the kakampi (ally) of grandchildren being disciplined by their parents or bullied by their peers. Lolas are depicted as either the kontrabida (antagonist) if she comes from a rich family, or as someone very gentle but overprotective if she comes from a poor background. Either way, the lola is portrayed as always having the best intentions at heart for her family.

A typical household in highly urbanised Manila often includes three generations living together. The majority of these families are third or fourth generation descendants of rural migrants whose poverty and landlessness pushed them to urban centres in search of work. As the cost of living is more expensive in cities, families are forced to reside in cramped spaces to reduce expenses. The middle generations in each family often earn a living through employment that keeps them away from their children. It is common for urban poor households, for example, to include fathers who work in other cities or regions on a seasonal or prolonged basis, or mothers who work as house helpers for families in gated subdivisions. Children from rural areas who go to study in urban centres usually stay with their city-based relatives as well.

Because of these arrangements, care work and parental duties are often relegated to other family members. It is usually the lola who handles the management of the household. The lola cleans the house, cooks most meals and actively participates in child-rearing. She is an active agent of socialisation, imparting cultural values and religious ideals to her grandchildren.

This, too, is frequently the case for families of overseas Filipino workers. Filipinos have been a big part of the transnational exodus of labor to many parts of the globe. This makes it common to see “skip generation” households in urban and peri-urban areas, where old or aging people live with their grandchildren while the children’s parents toil overseas, sending remittances as often as they can.

Yet the contribution of these lower and middle class lolas to the family—however immense—remains for the most part unrecognised and underappreciated. Conditions of poverty and joblessness oftentimes render them invisible in family decision-making, and the dominant non-recognition of care work as actual and important labour adds to this invisibility. It is precisely because of this lack of recognition that calls for more comprehensive state support for the Philippine’s aging population has failed to significantly enter public discourse.

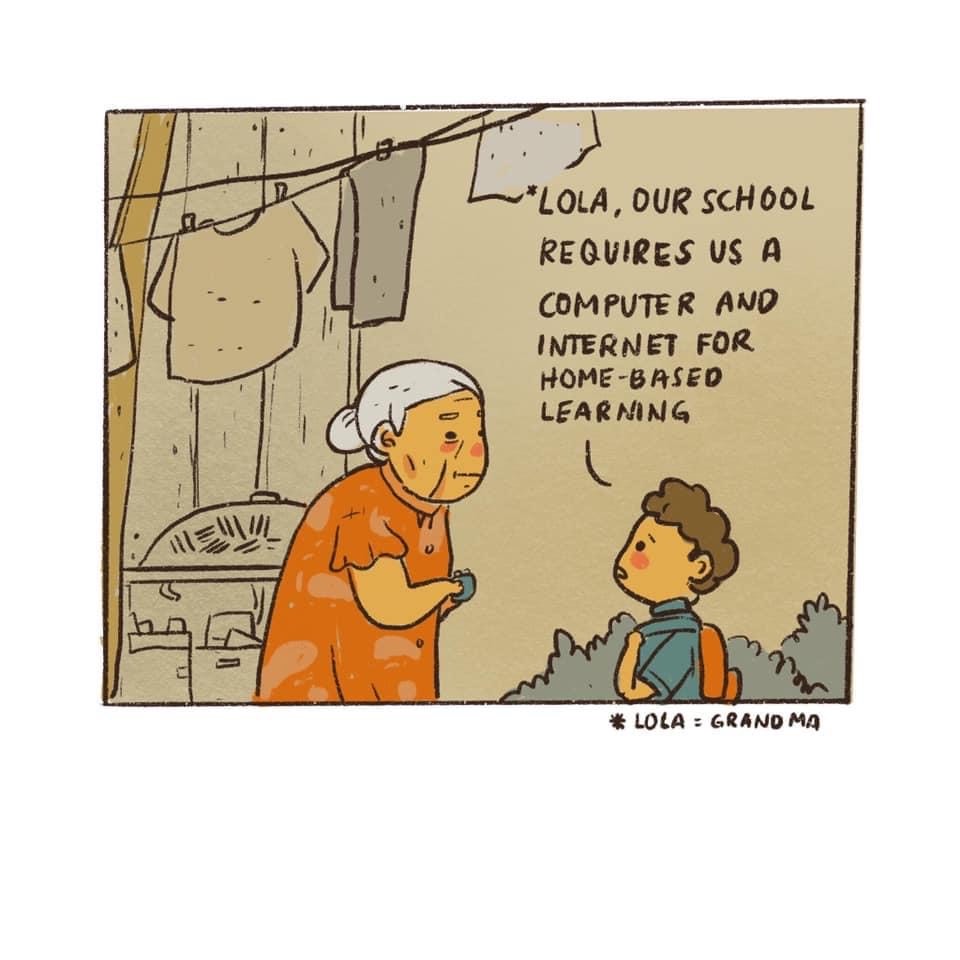

Lolas, especially from poor or middle class families, often assume the role of custodian parent. Forced to retire by age 65, they usually take on odd jobs such as cleaning homes and doing the laundry to augment family expenses. A cartoon from the artist Xiaoness.

Social security excludes the most vulnerable

Even before the coronavirus pandemic, the rights and welfare of older adults were not well cared for by the Philippine state. Lolas continue to do care work for their families but often without any social support. The national retirement program, for example, fails to include the most vulnerable segments of society. Older individuals employed in the informal sector are excluded from receiving retirement benefits, making it doubly hard for aging people from the lower and middle classes to get by upon leaving the workforce.

The Help Age Global Network has found that even if one does qualify for the social security program, the pension—which equates to about US$12 dollars per month for Filipinos 77 years or older—is not able to sufficiently cover an aging person’s living expenses and health needs.

The current pension scheme also fails to account for the reality that a considerable number of old people are still the primary breadwinners of their families. Due to the large percentage of children and young people in the country, there is a high dependency ratio—more and more children depend on their older family members. Many aging Filipinos are not able to save up for retirement because they need to provide for the needs of their dependents.

Meanwhile, the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps), patterned after the conditional cash transfer systems of Brazil and Mexico, aims to provide conditional grants to address the short-term financial needs of poor Filipino families. But it has yet to be expanded to cover the needs and allay the poverty of older adults. At present, the 4Ps prioritises the health and education of children from poor households, covering expenses such as health check-ups and school enrolment. It does not provide access to healthcare services or have direct benefits for older people.

Finally while there is some merit in the Expanded Senior Citizens Act of 2010, which provides discount privileges for select goods and services to the elderly, it mistakenly assumes that they have purchasing power in the first place.

Protecting lolas from the virus

Older people are extremely vulnerable to the coronavirus, but an adequate response to their urgent needs has sorely been lacking. In the Philippines, government relief packs have reached only a minority of the population and contain less than the bare minimum needed for survival—a pack of instant noodles, a few kilos of rice, and a sparse number of canned goods. These can only do little to cover the basic nutrition needs of children and the elderly. Relief programs also fail to account for the various medical needs and conditions that are disproportionately found in older and more vulnerable populations.

Actions under the Social Amelioration Program (SAP), created by the government’s social welfare department to reach vulnerable sectors affected by the pandemic, have been slow and small. The SAP is part of measures under the Republic Act 11469, or the Bayanihan to Heal as One Act, the government’s intensified effort to provide financial assistance to Filipinos to curtail the effects of the pandemic. A family qualified for the SAP pay-out is given around Php 5,000 to 8,000 (or US$100 to US$160.) Application requirements are so stringent as to make it almost impossible for poor families to get aid. Documentary requirements, for example, demand applicants have government IDs to become beneficiaries. But those who work in the informal sector usually do not have IDs, or even copies of their birth certificates. Senior citizens who receive a monthly pension are also disqualified from receiving cash aid.

Lolas have not even been spared from the Duterte government’s string of mass arrests during the pandemic. Lola Dorothy Espejo, a 69-year old grandmother living on the streets of Manila, was arrested by barangay officials for not complying with the curfew during the lockdown. That she was homeless and jobless did not seem to matter to the barangay.

Rodrigo Duterte’s war on COVID-19 is a war on the Filipino people

Reports emerging of anti-communist attacks in cities and rural areas, arrests of activists and union members, and military action in spite of a declared ceasefire.

We can help our lolas by urging the state to recognise the social safety nets and economic benefits that our grandmothers’ custodial parenting provides. In the United States, for example, it has been estimated that grandparents’ caregiving saves the government around US$23.5 to $39.3 billion annually. Other interventions that the state can look into include increased access to free and quality health care services and medication, the provision of relevant community wellness programs for senior citizens, and the provision of housing for poor and grandparent-led families.

The pandemic has set the stage for the rethinking and overhaul of socioeconomic systems. It has also drawn attention to the gaping holes left by profit-oriented healthcare and governance. In our on-going conversations about what a new and better normal might look like, we must create a warm and caring space for our lolas. We cannot leave her behind.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss