The Cambodian National Rescue Party (CNRP) leader Sam Rainsy left Cambodia in 2015 escaping political charges. Two years later, party president Kem Sokha was jailed on treason charges. Rainsy has since made it his mission to create a sense of urgency among the world’s leaders to intervene in Cambodia lest democracy come to an end.

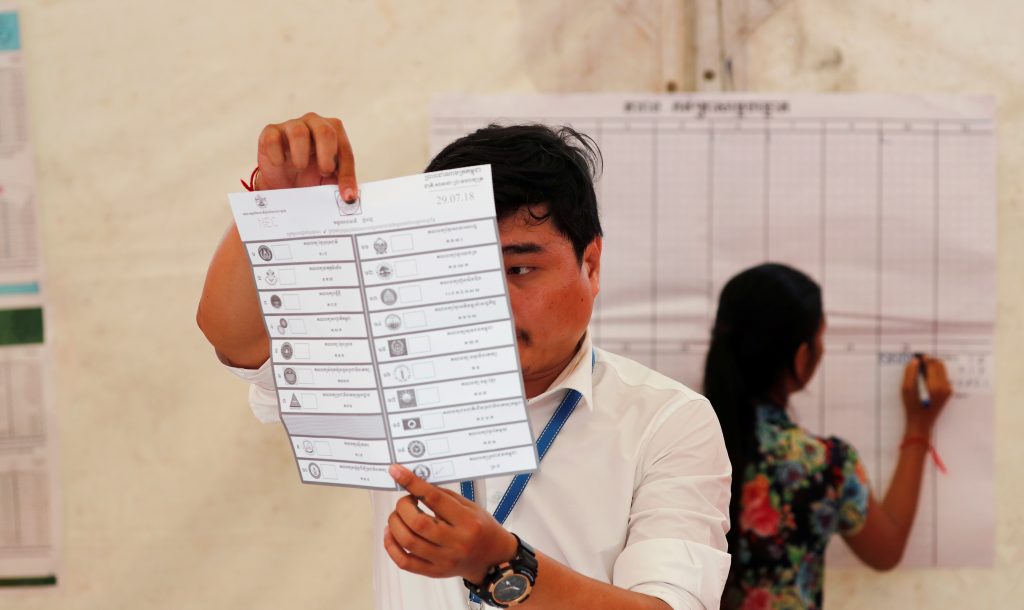

Yet hundreds of fundraisers, editorials, speeches, rallies, and handshakes with foreign dignitaries and supporters in Europe, the United States, New Zealand, and Australia did not prevent the inevitable. Cambodia’s parliamentary elections in July 2018 went through as planned: without Rainsy, without Sokha, without the CNRP, and thus without any substantial opposition to perpetual Prime Minister Hun Sen. His Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) swept all available seats. With the CNRP dissolved by Cambodia’s Supreme Court in late 2017, 19 hitherto-marginal parties were the only remaining alternatives; these parties won no seats.

Even casual observers of Cambodian politics are aware of the pivotal role the 1991 Paris Peace Accords play in the opposition’s attempts to call foreign actors to action. Over the past two decades, the PPA consistently provided Rainsy and his fellow opposition members with a script to claim a special relationship—a common destiny, even—that binds Cambodia to the rest of the “developed, democratic” world.

In this narrative, the designers and signatories of the PPA are morally, possibly even legally, obliged to protect their legacy and the political system it created. The United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC) implemented the agreements and organised the first nationwide democratic elections in 1993.

To a certain degree, Rainsy’s key audience—the international community—seems amenable to these demands. Hun Sen’s 2017–18 crackdown on the CNRP, the independent media and civil society all drew swift condemnation from international leaders and their organisations. Financial and technical support for the election was withdrawn by the US and the EU as well as Japan, followed by threats to take further action should his government not reverse course.

Rainsy’s forced absence from Cambodia has thus only strengthened the symbiotic relationship between the opposition leader and the so-called international community: whenever it becomes obvious how little substantial influence they have on the design and direction of Cambodia’s political system they turn to each other for reassurance that they are relevant, powerful, and on the right side of history.

To many international observers, the vision conveyed in the exchanges is certainly appealing: it is that of a shared agenda and a strong, progressive political partnership on behalf of the Cambodian people. This is all the more so at a moment of democratic decline in the region, coinciding with an identity crisis of the West.

However, it is also problematic to turn to these public expressions of mutual affection in an attempt to get a sense for the ideas and motivations of those Cambodian political actors that remain committed to the country’s formal political institutions.

Stickers of Hun Sen and Cambodian National Assembly President Heng Samrin on a supporter’s face during campaign in Phnom Penh, 27 July 2018. REUTERS/Samrang Pring

A narrative of suspicion

In a series of interviews I conducted in the two weeks prior to the election in July 2018, the leaders of five of the participating non-CPP parties expressed their thoughts on the barrage of international statements, threats, and promises directed at Cambodia and its leaders in an attempt to convince Hun Sen to let the CNRP participate.

Those parties’ interests and motivations are under considerable scrutiny: Pich Sros had supported the dismantling of the CNRP, and his Cambodian Youth Party(CYP) briefly benefited from the subsequent distribution of the CNRP’s parliamentary seats. The Khmer National Unity Party’s (KNUP) Bun Chhay had been released from prison just in time for the elections. As for those parties considered to be more authentically interested in advancing democracy in Cambodia? “Sam Rainsy is defaming us abroad,” Sam Inn from the Grassroots Democratic Party (GDP) said matter-of-factly, “says that we are puppets of Hun Sen”. And Kong Monika, son of a former CNRP member and leader of the Khmer Will Party, likewise conceded that many see him as a “traitor”.

Many critics of the remaining non-CPP parties saw their suspicions confirmed when leaders of almost all competing parties decided to join Hun Sen’s Supreme Consultative Council after the CPP’s victory, in exchange for the honorific title of Ek Udom (Excellency) and a government salary (of those interviewed, only the Grassroots Democracy Party and League for Democracy Party declined).

It goes without saying that the timing of the interviews and their role as party leaders effectively obliged all speakers to defend the value of the electoral process against critical domestic and international commentators.

In this regard it is easy to see why many will dismiss these voices as the irrelevant thoughts of an irrelevant elite. After all, they decided to participate in the sham elections, providing legitimacy to a process that only served to further facilitate Cambodia’s “descent into outright dictatorship”.

Yet with every day that passes since the election, the tensions this conflict created become less and less important.

More importantly, there is the fact that the interviewed actors, regardless of their proximity or distance to the government of Hun Sen, consistently drew on similar narratives and themes when presenting their views of Cambodia’s relation to the international actors that are perceived to have an interest in their country.

These consistencies (in substance, not style) are further corroborated by the debates as they play out on social media and by a series of interviews that Julie Bernath and I conducted with Cambodian political activists, advisors, and civil society leaders in 2017 and 2018.

Taken together, they draw attention to the factors that determine the space and the scales that Cambodia’s politicians (including Hun Sen) use to situate their policies vis-à-vis foreign countries. In the amicable exchanges, that purport to draw solely on the spirit of the PPA when constructing transnational political alliances on behalf of the Cambodian people, these determinants are often hidden, downplayed, or ignored.

Chief among those recurring motives in the pre-election interviews was a tendency to view the international community as partisan, biased and acting on behalf of the CNRP.

Domestically, the repeated discursive interventions by foreign actors and their demands to reinstate the CNRP have thus contributed to revive the use of the politically loaded distinctions between Khmer “inside” and “outside” of the country. When conflicts ravaged the country in the 1960s and 1970s, knowledge about the whereabouts of a person became deeply entangled with perceived political affiliations as different factions used different provinces and border camps to recruit and train their followers, while others fled the country. Former refugees who returned to Cambodia in the early 1990s to support Cambodia’s liberal reforms were not always received with open arms. Instead, many envied and resented them for the opportunities they had abroad, while those “inside of the country” suffered. Now, Kong Monika deemed Rainsy’s call for an election boycott a bad strategy because “it will cause hardship for the people inside the country, [he] is outside … he won’t have security problems, he is safe.”

The party representatives reacted equally dismissively to the EU’s threat to withdraw trade preferences, which have been the bedrock of Cambodia’s garment-export economy. The EU recently announced that Cambodia may indeed be cut off from the Everything But Arms (EBA) scheme.

Such measures, this was the general assessment “won’t affect the people in power, it won’t affect the opposition leaders either. [It] will have an impact, it will affect Cambodia, but who will affect the most? The innocent people,” said Kong Monika.

Or, in a slightly more dramatic fashion, Pich Sros declared that “the people who will die first aren’t Hun Sen or Sam Rainsy”.

Aware of the potential ramifications this strategy may have for him, Rainsy told “all factory workers” that “when sanctions are mounted against Hun Sen and his regime by the international community, it will not be the CNRP that is to blame. [It is] Hun Sen, because he undermines democracy and abuses human rights.”

The question here is if their economically precarious situation leaves the affected people any chance to appreciate whatever long-term game it is that political leaders are playing when these measures begin to negatively affect their livelihoods.

Garment workers travel to work on the outskirts of Phnom Penh, October 2018. REUTERS/Samrang Pring

Moral superiority and hierarchies

On the ground, the constant criticism of Cambodia as “undemocratic” can also feed into a sense of resentment against the paternalism of distant observers. Unlike Japan, which was held up by the political figures as a model because it simply “helps Cambodia as a poor country” Western actors are often viewed to possess a false sense of moral superiority. Those speaking out in the name of the international community did of course expressly condemn the country’s ruling elite, yet, many do not take kindly to the hierarchies between Cambodia and other countries that such criticism establishes. In Prich Sros’ words:

“So international observers criticise Cambodia for being undemocratic. Undemocratic according to what standard? [What about] the Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam? The US is close to all of them! Why are they not threatening to end business with Thailand? Why is the US not applying any pressure to Thailand? […] Which standard are they using? Frankly, I haven’t seen it anywhere in this world, this ‘democracy’.”

And then there are the lessons learned from the country’s recent history of wars and conflicts. Foreign actors fanned the flames in all of them:

“Because we have learned from experiences that whenever we Khmer, when our country became dependent on one great power we were not at peace; before, during the Lon Nol period, we became solely dependent on the US and fought against communism, then later on, we became dependent on China and fought against the US. Every time we become dependent on a great power we are not at peace.” (Sam Inn)

These more recent experiences feed into a collective memory already profoundly shaped by images of shifting borders and territorial losses. As a result, it is an ambivalent mix of anxiety and pragmatism that feeds into politicians’ assessments of foreign actors’ motivations to cooperate and engage with a country like Cambodia.

Its neighbours? They are still overwhelmingly viewed with deep-seated suspicion by my interviewees. The border dispute with Thailand over Preah Vihear is still fresh on people’s minds and reports over documented “encroachment” from Vietnam—considered to be driven predominantly by its intention to “swallow” its neighbours—routinely serve to stir up the public.

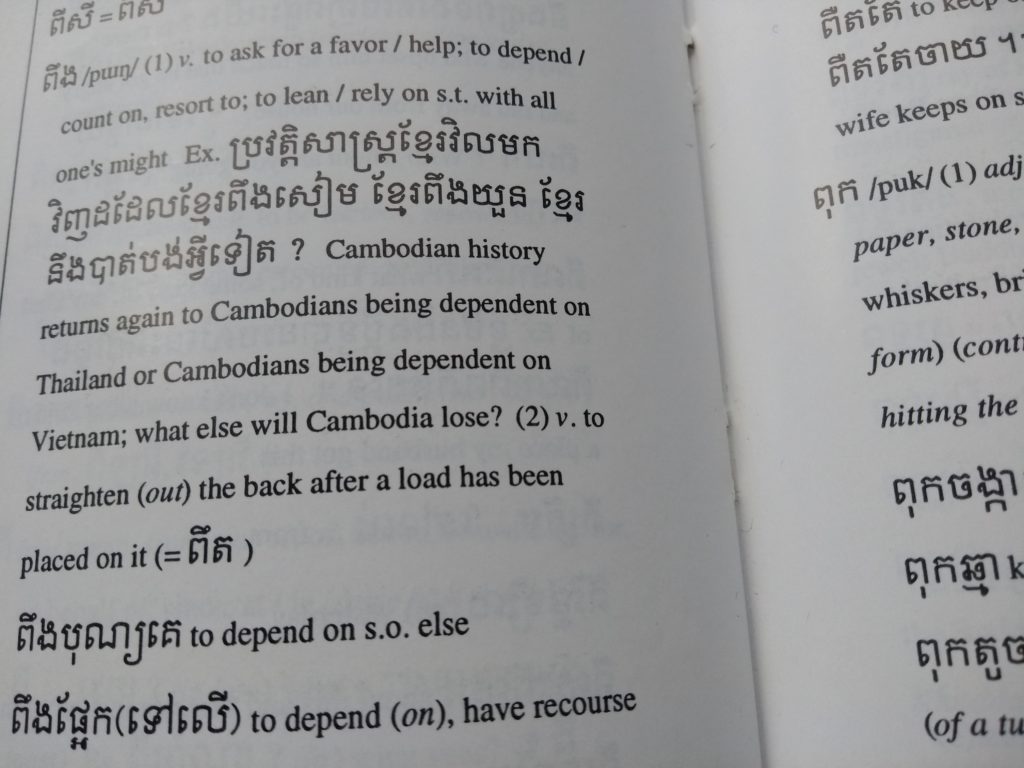

Entry in the Modern Cambodian-English Dictionary by Hedly, Chim, and Soeum (Photo: author)

China? It is mostly driven by self-interest in the party leaders’ eyes. It is seen to benefit from Cambodia through strategic investments and exploitative business practices:

“There are many Vietnamese and Chinese factories and the government is giving out land concessions and a lot of business to these factories. And all those factories do not have to do anything. They cut the trees, cut the trees and sell them. They mine, mine and destroy the Cambodian resources but they aren’t creating any work for Cambodians in this context.” (Kong Moncia)

Chinese support for the elections in July was thus not framed as an attempt to create a new one-party state in its image, but as a calculated move to stabilise its strategic position.

And the “international community”?

The predominant identity accorded to Cambodia as a country and nation in their interactions with representatives of the Western countries is that of an “aid” recipient. In an attempt to capture the general sentiment that was expressed during these interviews and those jointly conducted with Bernath, the American sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild’s observation about “gratitude” comes to mind: it contains not only a sense of appreciation, but likewise a sense of indebtedness. As such, the long and often heavy-handed involvement of donor countries has also given rise to notions of unease or even resentment. In the words of the LDP’s Kem Veasna:

“There are three groups of people that pretend to be generous: one, politicians; two, religious people; and three … the civil society […] They do this for a salary. […] I talk about this a lot in public forums. I am against the international community.”

In this regard, Monika’s statement reads like a final stroke under the views expressed by all interviewed politicians:

“I think that there is a political deadlock in Cambodia today that can only be overcome by a dialogue between Khmer and Khmer. We cannot always rely on foreigners for help … we have seen historically that, asking this side for help or that side for help … those who are the victims [of this strategy] are the Cambodian people.”

A new rhetoric

The Cambodian people harbour no illusions when it comes to the intentions of anyone “elected” to power to act in their interest. A few days prior to casting her ballot, a teacher summarised her expectations with a Khmer proverb that loosely translates to: “before the election they court you, after the election is won, they club you”.

And while such criticism is mostly aimed at the government, it also becomes increasingly difficult to speak of Cambodia’s opposition parties without putting the very term in ironic quotation marks. Yet, those actors and institutions that should have a vital interest in facilitating a constructive dialogue between Cambodians—among them ASEAN and the politically active diasporas in the US and Australia—should still take note of all areas of contention and dissent that were mapped out here.

The anxieties, concerns, and resentments expressed here are sparked by others’ perceived interest in their territory, their resources, but also the tensions caused by what Berit Blieseman and Florian Kühn referred to as the paradox of the international community (likewise, a concept that deserves its quotation marks): it is possible to morally exclude Hun Sen and his government from the international community, yet, structurally Cambodia—the country and its people—will remain part of it.

Kem Sokha studying the Paris Peace Accords. Cover of book by about the opposition leader, authored by Chhay Sophal, 2016 (Photo: author)

Many remain committed to the vision of the 1991 Paris Peace Accords. Yet, the exiled opposition needs to find ways to evoke its principles without waving the paper. This decade-long practice has closely associated the PPA with partisan, not universal, claims. As a result, international alliances forged in its name cannot rely on their good intentions. Instead, the ”international community” needs to evaluate to what extent they need a domestic political constituency able and willing to support the rationale for their interventions.

In the absence of such voices, and the government’s near monopoly on the media, can blunt measures like the proposed EU sanctions—with their simultaneously vague and extensive goals—really succeed, or are they more likely to lead to the type of “perverse effects” observed elsewhere?

Considering the prime minister’s firm control over Cambodia’s political and economic institutions and his proven ability to exploit the tension caused by conflicts and disputes in all those three areas, a thorough review of democracy promoters’ rhetoric and strategy might well be overdue.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss