Facebook started with a promise. It levels the playing field in the market of ideas. It amplifies the voices of those who do not have access to mainstream media. What started as a platform to rate girls in Harvard has evolved to become an indispensable tool for democratic politics, whether it is for Podemos in Spain, Barack Obama in America or the protesters of the Arab Spring.

The year 2016, however, was a reminder that what promises progress can also portend trouble.

The Philippines knows this story well.

Patient Zero

The Philippine is “patient zero” in the era of networked disinformation. Networked disinformation refers to the use of digital media to deliberately manipulate and confuse the people.

This pattern of online behaviour is often associated to Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte’s troll army. Similar to Vladimir Putin’s trolls paid to work for twelve hours to praise the Kremlin and attack Russia’s dissidents on social media, Duterte’s keyboard army are paid to threaten citizens and bully journalists critical of Duterte.

For two years, I was part of a research team that investigated the character of the Philippines’ troll army. I spent months reading these comments, often using a combination of sexist tirades and violent threats. “I hope she dies soon like his husband,” one troll said, referring to Vice President Leni Robredo, a known critic of the president. Many called for the gang rape of female journalists publishing unsavoury reports about the Duterte regime.

The vitriol online has alarmed many—from journalists to academics, the Roman Catholic Church to politicians.

Trolls target journalists first, Maria Ressa observes, “and they attack in very personal ways with death threats and rape threats.” Ressa is the CEO and executive editor of Rappler, an online media company based in the Philippines. She has been too familiar with these online threats that she has lost count of how many she receives in a day.

So troubling are these patterns of behaviour that the Philippine Senate conducted an inquiry on this issue. “The internet should be a positive resource,” one Senator said, as the nation continues to be exposed to fake news. Eighty-eight percent of Filipinos who are online have read fake news, one poll finds, establishing the prevalence of this problem.

We can only expect for this to intensify in the coming months as the campaign for the midterm elections heats up. Already, we monitor posts about candidates being portrayed as the enemy of the state, hence deserve a #ZeroVote. Has democratic Philippines succumbed to illiberal social media?

To meaningfully answer this query, one must take a longer and broader view of social media use in the Philippines.

A longer view

A long view reminds us that the Philippines has always been a trailblazer in social media use. A country whose main export is its own people relies on digital technologies to keep families together.

For many, online interactions are as important as face-to-face communication to maintain family ties. Filipino millennials grew up with ”parenting at a distance” where talking to relatives over mobile phone or Skype is the norm rather than the exception. What emerges from this phenomenon is a generation at home in the digital public sphere.

Consider the following statistics. In the Philippines, mobile phones outnumber people. The country has the highest social media use in the world for the past three years, with Brazil at second place. SMS companies bundle free Facebook as part of their promotions, making social media the main entry point for the internet among young Filipinos. The country spends average of 3 hours and 57 minutes a day on social media despite an internet speed rated as one of the lowest in Asia.

A long view of digital media usage in the Philippines suggests that there is a population readily receptive to information propagated in digital platforms. Networks of disinformation are formed because there is an established online network.

A broad view

Meanwhile, a broad view leads us to realise that the problem of disinformation extends beyond the political realm. In fact, what gives it life are associated industries that are not political in nature.

In our research on political trolling, we find that networks of disinformation are buoyed by the Philippines’ position in the global economy. With a service industry composed of tech-savvy youth, the Philippines is among the first to offer a suitable workforce for digital labour. The Philippines now has the third highest-earning online freelancers in the world. This labour force is a stockpile of digital weapons that can be utilised for different political ends.

Political disinformation projects have its professional roots in advertising and public relations industries. Disinformation techniques for politicians were first tested in advertising and public relations campaigns for commercial products such as soft drinks and shampoos. Our study finds that architects of disinformation—those that broker supply and demand for fake news—play a central role in perpetuating this industry. The online trolls who have been at the receiving end of moral panics are at the bottom of the pecking order.

Illiberal politics for sale

Understanding the networks of disinformation using a long and broad view provides insight as to why social media, when used for political purposes, can have toxic implications for democratic life. When treated as a business, illiberal cultures can be manufactured, peddled and used to influence the conversation.

But how exactly does this work? The Philippines can offer three crucial lessons for the world.

Lesson 1: The prime role of influencers

There used to be a time when celebrities can make or break a candidate’s political career. The teleserye-obsessed nation needs singers and actors to draw crowds in sorties, make an appearance in glossy advertisements and raise the hand of politicians.

This is no longer the case. Today, it is anonymous online influencers that can hold the success of political campaigns.

Anonymous influencers occupy the middle ground in the networks of disinformation. The accounts they operate are anonymous, which means the owner of the account is unknown, and their identities cannot be traced. They have a massive online real estate with organic followers ranging from 50,000 to 2 million.

What is the content of these accounts? Nothing spectacular. The aim is to entertain and therefore sustain followers. These accounts post inspirational quotes, say something about commercial brands or films and promote an advocacy every now and then. They have mastered strategies of making something trend. From the language used to the time a meme gets posted, these anonymous influencers are skilled at slipping in paid promotional content to make it appear organic.

Unlike accounts Facebook deleted for violating its “spam and authenticity policies”, anonymous influencers operate under the radar. They walk the fine line of avoiding divisive forms of disinformation that call attention, while also amplifying a storyline that benefits a particular political agenda.

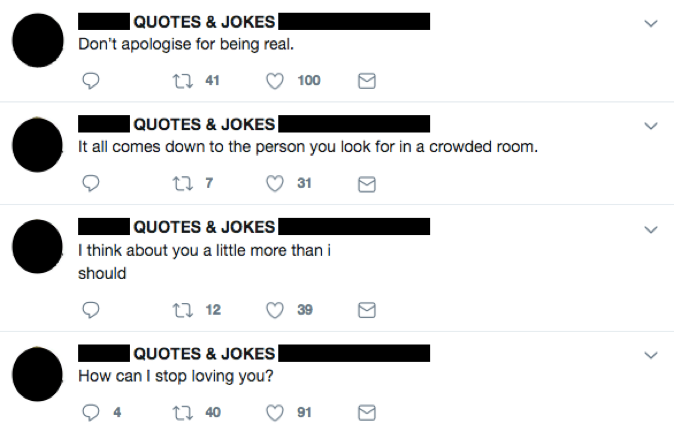

Take the case of the Twitter account below.

Anonymous influencer “Quotes and Jokes” retweeted the post by a Twitter account that supports Bong Go. Go is Duterte’s right hand man. He is running for Senator in 2019.

The tweet reposted by the anonymous influencer features Bong Go with Duterte during the wake of policemen and military officers killed in clash in the island of Samar. The post is a classic propaganda material where photos of candidates with ordinary people are presented, curated to evoke a sense of compassion and engagement.

This anonymous influencer account has over 250,000 followers. Only a handful of posts are actually about Bong Go because ordinarily it only posts about life quotes, jokes, and memes. Examples of this are below:

This tactic of promoting a political candidate may seem harmless. How bad can one political endorsement be? And how different is it from amplifying the advertisement of a commercial brand?

Aside from this practice falling off the radar of campaign finance laws, this sinister approach to political campaigning can reshape the character of political conversations online.

Anonymous influencers hold power for they produce information that seem natural—from love quotes to film endorsements, to politicians portrayed as compassionate people. That these actions seem harmless is precisely the point. It insulates political posts from intelligent critique and accountability—two virtues necessary to deepen electoral democracy.

Lesson 2: The importance of keeping machine politics

Networks of disinformation perpetuate and further entrench personality-driven politics.

There is a growing interest among politicians to utilise social media in their campaigns. In our research, we found that politicians, down to the local and village level, are offered crash courses on effective online campaigning. The course covers a range of tactics, from the basic use of Facebook advertising to the most sophisticated ways of online branding. These courses cost between PhP 3,500 to 5,000 (AUD$ 90 to 130) for a one-day seminar.

One might hope that politician’s desire to use social media is to better reach and engage with their electorate. This is naïve, to say the least.

Drawing from recent election campaigns, politicians in the Philippines have used social media like their counterparts in developed countries. It is used mainly to deliver messages and promote themselves rather than to deliberate with their constituents.

Social media is used for positive campaigning to improve and manage the image of politicians, and negative campaigning to condemn the image and smear the reputation of rival candidates. Black propaganda takes many forms but often use the formula of accusing opposition politicians to have affairs with journalists, or journalists being paid by opposition politicians.

Senator Antonio Trillanes, for example, is one of the many who has been on the receiving end of online attacks for his staunch criticism of Duterte and his allies. Our database has numerous entries of Trillanes memes. There was one when he was called “Trollanes” with his face edited to fit the photo of a cartoon troll. There was one where he was lying in a deathbed. And many are memes with him portrayed as an effeminate man.

In September 2017, at the height Duterte’s accusations against Trillanes of maintaining secret bank accounts in Singapore, there was another “scandal” circulating online—his alleged relationship with ABS-CBN news anchor Karen Davila. In the post below, Davila was accused of having an affair with Trillanes as she appeared to be defending him against Duterte’s allegations. However, the post links to a non-existent website.

Black propaganda, of course, is not new. This makes social media less of a disruptor but an amplifier of existing political cultures. It makes a case for further building a political machine, not just among local brokers that can secure support from villages but among architects of disinformation.

Lesson 3: Silence is more important than voice

Mainstream media experiences dwindling trust and credibility as source of political news. This, however, does not mean that social media is taking its place. Rather, we are witnessing a reciprocal relationship between the two.

Disinformation campaigns tell multiple and competing truths to confuse and diffuse the quality of information. When mainstream media decides to cover competing truths, they oxidise disinformation.

An example of this is when news agencies choose which issues to amplify or which hashtags they think deserves attention. Most of the time, it is the viral or trending contents that make it to the mainstream.

We have seen this play out when there is an attempt to create a noise on a specific issue. In September 2016, #IlibingNa (#BuryHimNow) drew an online clamour to persuade the decision of the Supreme Court regarding the burial of Ferdinand Marcos at the Heroes Cemetery. A hashtag is crucial for an online community to come together and where users can participate in ongoing discussions. This is true for this hashtag too as Marcos loyalists used it to show their support. There was an online petition circulating to appeal to the Supreme Court’s decision on the case and a barrage of memes and photos embossed with #IlibingNa to support the cause.

But the hashtag was taken forward to a broader agenda. It successfully drew the attention of media and brought the cause of these loyalists to mainstream. Getting mainstream coverage is a big leap in forwarding fringe beliefs to public conversation, which was proven useful for Marcos supporters in fighting the bigger force that was against the burial of the dictator.

The journalistic practice of using social media for story ideas is problematic. Some cautioned news agencies that this practice allows politicians to further set the political agenda, thereby tilting the balance in favour of politicians over journalists. It also leaves news organisations open to the manipulation of digital influencers. Even if the media is reporting a story to debunk it, they nevertheless fall to the bait of the architects of disinformation whose main goal is to get coverage in the first place. This leads some to argue that media agencies should agree on strategic silence so as not to amplify disinformation.

How media organisations in the Philippines will put this in practice, however, is another story.

Social media and elections in the Philippines

As I was writing this piece, I received a survey question from Facebook asking if I consider it “good for the world”. Facebook says they would like to do better. Better for whom, I wondered.

Did Duterte change the rules of Philippine elections?

Dutertismo still hasn’t fundamentally changed how political power is sought and won.

As to what one step ahead means is an open question.

In this piece, I shared the story of the Philippines—a young tech-savvy nation suffering from the consequences of disinformation.

Fake news and online trolls have perpetuated a culture of illiberalism in the digital public sphere, which corrodes the quality of democratic life.

There are reasons to be pessimistic about the future of political campaigns in the age of social media, but, as Philippine political history also teaches us, we must also be ready to be pleasantly surprised.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss