Versi Bahasa Indonesia bisa dibaca disini.

Conflict, disappointment and fear have followed the opening of the major quinquennial art exhibition Documenta 15 in Kassel, Germany on 18 June, as accusations of anti-Semitism were levelled at participating artists’ collective Taring Padi and, not for the first time, at artistic directors, Indonesian collective ruangrupa. Both groups reject the accusations of anti-Semitism and have apologised for failing to recognise the offensive nature of the image/s within the enormous and densely populated banner The People’s Justice. After initially being shrouded in black cloth, it has now been dismantled.

The fallout has been severe and the reactions strident and emotive, both in Germany and in Israel. On Twitter the Israeli embassy derided the artwork as “old-style Goebbels-like propaganda” while German Minister for Culture stated that she had been “betrayed” by Documenta’s management and the curators, who had undertaken to ensure anti-Semitism had no place in the exhibition. In Indonesia and elsewhere the incident, and more particularly the response from authorities, has reignited paranoia about Zionist conspiracies and fuelled a growing sense that organisers are beholden to conservative xenophobic forces that are disinterested in, and actively repressive of, constructive dialogue.

When their selection as artistic directors of Documenta 15 was announced in 2019, ruangrupa called attention to the festival’s origins: “If documenta was launched in 1955 to heal war wounds, why shouldn’t we focus documenta 15 on today’s injuries, especially ones rooted in colonialism, capitalism, or patriarchal structures, and contrast them with partnership-based models that enable people to have a different view of the world.” Including collectives from around the world, and especially those societies impacted by colonialism, ruangrupa proposed a curatorial framework they called “lumbung,” a term borrowed from the Indonesian word for a communal grain store.

Their approach aimed to be horizontal, cooperative, community-oriented, inclusive and experimental. But from early 2022, the inclusion of Palestinian artists’ collective “The Question of Funding” and the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center attracted the attention of a blog accusing the artistic directors of anti-Semitism, based on the inclusion of “anti-Israeli activists”. These accusations were discredited but were nonetheless repeated in mainstream media. Ruangrupa rejected what they described as “racist defamations” and affirmed a commitment to “the principles of freedom of expression but also a resolute rejection of antisemitism, racism, extremism, Islamophobia, and any form of violent fundamentalism are the underpinnings of our work.”

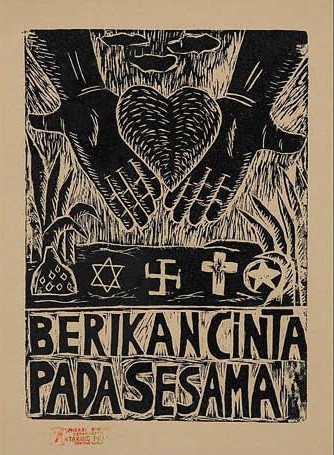

“Give love to all” from the Humanity poster series by Taring Padi, woodblock print on paper, 40cm x 53cm each, 1999. With permission of the artists.

There is no doubt that parts of The People’s Justice draw on anti-Semitic imagery. In amongst the images of skeletons, weaponry, soldiers and spies from the Cold War’s major geopolitical players and their victims—intended to critique the globalised military machine that did indeed conspiratorially support the massacre of hundreds of thousands of Indonesians in the “anti-communist” purges of 1965—is a suited figure with sidelocks and a hat typical of orthodox Jews—alongside these stereotypical attributes the figure also sports red eyes and pointy teeth and worse (and perhaps tellingly anachronistically), the SS insignia on his hat.

How an image like the one described above escaped the attention of organisers, who had publicly committed to ensuring there were no elements of anti-Semitism, is worth interrogating. Further, the mistake raises important questions about the artists’ creative process, the curatorial framework adopted by the artistic directors, and the organising institution’s reactions to external pressure exerted through the media, government and diplomatic representatives. The latter are questions for those responsible to consider seriously. Here, as art historians, we will foreground the context from which the artwork, and the curatorial framework, emerged and what opportunities and challenges are presented in its transposition to Germany.

Lumbung as curatorial practice

“As a concrete practice,” write ruangrupa on the Documenta 15 website, “lumbung is the starting point of documenta fifteen: principles of collectivity, resource building and equitable distribution are pivotal to the curatorial work and impact the entire process — the structure, self-image and appearance of documenta fifteen.”

Artists were grouped into collaborative “mini-majelis” (councils) of half a dozen or so artists and collectives, who met regularly (virtually) in the months before the exhibition proper to discuss their respective work and how to distribute the funding “pot” allocated to them. Larger “majelis akbar” or plenary meetings were held every few months and acted as a forum to which each mini-majelis reported back. According to Christina Schott, within the mini-majelis that Taring Padi belonged to, artists were challenged by the sudden expectation to make decisions about matters with which they have no experience. Schott quotes Setu Legi from Taring Padi as saying: “… the needs are very different. But what I like about the system is that no one is left behind, while others become the highlight, simply because they have the better resources.”

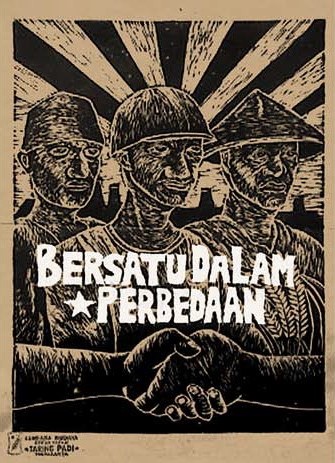

“United in diversity” from the Humanity poster series by Taring Padi, woodblock print on paper, 40cm x 53cm each, 1999. With permission of the artists.

This communitarian approach is typical of agrarian and indeed urban communities in Indonesia, where the collective is a common form of social organisation and often, social surveillance. It forms a protective bubble which at times can lead to insular perspectives and naivete of the broader context—whether that be the experiences of those outside the bubble, or the social milieu in which it is situated. In our conversation with Taring Padi a few days after their banner was removed, they had no recollection of discussions on the sensitivities of the politics of representation in Germany or the specific historical context that led to it, either in their mini-majelis or the larger meetings. This seems discordant with the artistic directors’ earlier commitments to ensuring no such sentiments would emerge; basic intercultural sensitivities should have been a point of discussion, especially considering the visceral threats of racist violence that were evident when The Question of Funding’s space was vandalised in May.

The experimental lumbung framework promulgates admirably horizontal egalitarian values and breaks down the institutional hierarchies that have allowed art events around the globe to be hijacked by banality, elite vested interests and empty spectacle. It allows artists to connect their work more directly to audiences and to connect to each other. Artwork is no longer filtered through the lens of curatorial thematics and silos of selectivity, and relational forms are not dictated by public program professionals.

But these great rewards come with great risk. Cultural institutions are notoriously risk-averse, with the primary motivation being to avoid reputational damage. A side-effect of this reputational risk aversion is that contextual and cultural sensitivities are usually managed, and creating a safe environment for audiences, artists and artworks is prioritised. All of this is achieved through a hierarchy of responsibility which ultimately means the institution has a duty of care to all its stakeholders. Artists, at the bottom of the institutional hierarchy but simultaneously the most visible part of it, are somewhat off the hook. It’s a paradox that also deserves scrutiny, and experimental methods like lumbung take this on.

Although it is not an unusual approach to creative and curatorial practice in Indonesia, the lumbung framework does not appear to have found an adequate mechanism to distribute risk and responsibility within the heightened tensions of Germany’s own struggles with present day Islamophobia, and the historical burdens of the Holocaust. While this context produces a particular sensitivity, any context unfamiliar to artists and curators will do the same; the politics of representation and its attendant taboos exist everywhere in different forms. Whose responsibility is it to ensure these are understood and incorporated into alternative models of knowledge-sharing when they are imported into a new context?

There are also important questions to be asked about how the visual is accounted for in this framework. While the focus on process, concept and dialogue is paramount to opening art events up to more diverse and pluralistic voices and revealing the experiences of those not accounted for in hegemonic social discourse, it is nonetheless true that the vast majority of visual art involves representation and sensate experiences that viewers will receive subjectively. Critical discussions of image, representation and power should always be a part of preparations to exhibit, both to manage risk and to ensure the works are tested against a variety of potential interpretations. Artists deserve no less than the opportunity to ensure their artwork does not unintentionally misrepresent their position.

Taring Padi: collective practice and its socio-political context

In our interview with Taring Padi, they were at pains to stress that they did not hold ruangrupa or the lumbung framework responsible for the chain of events that allowed the banner to be displayed despite its triggering imagery. They remain apologetic for the offense caused but insistent that it was unintended, both in the original rendering of the image for the also-controversial 2002 Adelaide Art Festival and in the failure to identify its potentially inflammatory reception in Germany 20 years later.

Whatever the weaknesses of the lumbung approach, its open platform has allowed Taring Padi to receive a groundswell of support from visitors to Documenta 15 and residents of Kassel, who have brought gifts, food, love and solidarity. Members of the group told us that one visitor undertook to go through many of the works on display with them, looking for other images that might cause offence and openly listening to their explanations whenever a query was raised. In this way, lumbung may also allow dialogue to continue outside the institutional and media frameworks that seem intent on stifling a nuanced discussion of what has taken place. This conviviality, at least, is familiar territory for Taring Padi, whether in Germany, Indonesia or elsewhere.

Taring Padi’s own convivial, collective approach to art is crucial to understanding why there are no simple answers to the question of how the offending image appeared in the banner in the first place. Not only does Taring Padi have many members who are involved in the creative process, but they also often invite non-members such as workshop participants to contribute to works in progress. While large-scale works are planned through discussion, notes and sketches and the division of labour is coordinated (though not strictly enforced). It is a process that deliberately eschews authorship—works are not signed by individuals but instead stamped with the collective’s distinctive logo. As Bambang Agung wrote in Taring Padi: Seni Membongkar Tirani (Art Dismantles Tyranny), “Collective artworks, in other words, are a critique of the reification of art and the commodification of its artists.”

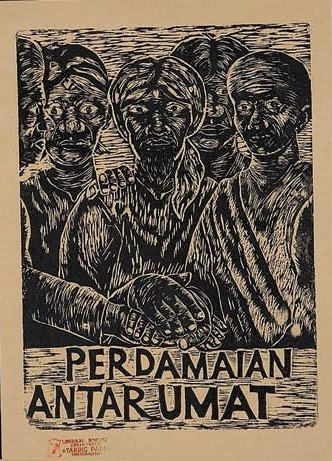

“Peace between the faithful” from the Humanity poster series by Taring Padi, woodblock print on paper, 40cm x 53cm each, 1999. With permission of the artists.

The imagery delivered through this process is inevitably derived from a diverse range of sources and linked to the leftist ideologies embraced by the collective, which is by nature amorphous. They deploy caricature and humour and shared this visual strategy with many Indonesian artists, including Apotik Komik, Heri Dono and Eddie Hara. Their overall approach is direct and focused on delivering a political message. Their woodblock prints, made on cheap brown paper and often pasted up on walls or distributed through social networks, often feature imagery that echoes the social realism of Kathe Kollwitz. Their murals share the compositional strategies of Mexican Muralists like Diego Riviera; in short, their visual influences are also political. The collective also deploys a reductive strategy in which figures are represented as (stereo) “types” (farmer, woman, politician, preacher). Meanwhile, the anthropomorphising of pigs and dogs into figures of derision echoes cultural and linguistic attitudes to these animals in Java and in global parlance (capitalist pigs, watchdogs etc.). It is in this social context that the depiction of Jewish figures with fang-like teeth and blood-red eyes is likely to have originated. In Muslim-majority Indonesia, where pro-Palestine attitudes are normative, such imagery would barely raise an eyebrow. But as Documenta 15 demonstrated, it is a different story when the work is displayed in the country responsible for the Holocaust.

Nevertheless, the question of social context is vexed. Of the dismantled work, Taring Padi says: “’People’s Justice’ was painted almost twenty years ago now, and expresses our disappointment, frustration and anger as politicised art students who had also lost many of our friends in the street fighting of the 1998 popular uprising that finally led to the disposal of the dictator.” Moreover, the content of the work drew on then-emerging scholarship that revealed the complicity of Western democracies in the systematic exacerbation of political and social instability in Indonesia in the 1960s–designed to bring down the Indonesian Communist party and the incumbent president who sympathised with their agenda. These tensions, of course, led to the 1965-66 massacre of at least half a million citizens, the detention of many more without trial, and the installation of the authoritarian New Order military regime. Taring Padi’s controversial banner explicitly implicates Mossad as a supporter of the New Order, a fact confirmed by Israeli Foreign Affairs documents unsealed in the state archives.

Yet, while a reference to modern Israel’s intelligence agency may be seen as legitimate criticism of Israel’s role in Cold War politics, the other image that has drawn the ire of German and Israeli commentators is more slippery. The depiction of a side-locked, suited figure clearly draws on the kind of anti-Semitic propaganda that has long circulated widely in Europe. For those whose education and social context have taught them to critically evaluate such imagery for this specific expression of hate, the reference is explicit and obvious. For artists embedded in a different social context, it may be less obvious. Given that Taring Padi has long been known to espouse values of religious tolerance and humanity, however, it is important to ask how such an image could appear in their work?

Religious minorities in Indonesia face discriminiation

"Spineless politicians, feckless government bureaucrats, and narrow-minded ulama officials" stand in the way of religious freedom in Indonesia.

Anti-Semitism in Indonesia

As one of the largest Muslim populations in the world, Indonesia does not have diplomatic relations with Israel. Anti-Semitic sentiment can be traced back to colonial officials and European travellers in the 19th century who systematically applied European stereotypes of Jews to local Chinese populations across Southeast Asia. Compounded by such legacies of colonial rule that deny many Indonesians education in critical thinking, unfortunately, anti-Semitic sentiments are quite widespread. In 2002, when the world was awash with post- 9/11 Islamophobia, the response in Indonesia to the events in the US was different. Compassion for victims soon gave way to anger and fear that Islam as a whole had been made a scapegoat. It was a turning point that emboldened already active terrorist groups and inspired the Bali bombing in October 2002.

A frightening dichotomy between Western imperialists and the rest of the world gained traction, and stereotypical images of capitalists, imperialists, and Zionists were—and continue to be—disseminated uncritically through certain circles. It is not beyond comprehension that in this environment a poorly understood—or indeed completely unrecognised—image of a nefarious man in a suit seemed an appropriate image to represent the state of Israel, alongside a giant pig wearing an Uncle Sam hat, and another pig wearing a peci (also known as a songkok or kopiah). The jarring and confusing application of the S.S runes deepens the image’s shock value but also begs more questions: what is the intention of the image and how informed was its author? Was there any real comprehension of the symbology or was it uncritically borrowed from the mass of imagery circulating in a public discourse that conflated anti-Semitism with anti-imperialism and anti-capitalism?

There’s a lot to unpack there and it’s a wonder that imagery in this work hasn’t triggered negative reactions from other audience segments in the past. Taring Padi acknowledges that their approach may have been “sloppy and careless”. This experience, they told us, will lead to a more careful approach to the impact of images. Unfortunately though, Documenta is now unlikely to provide a platform for the artists to explain what such a more careful approach may look like. Hyperbolic accusations that the artwork reflects Goebbels-style Nazi sentiment have fuelled extremist, reactionary responses and created a dangerous atmosphere in which artists’ safety is threatened. Institutional and governmental reactions have prevented constructive discussions that contextualise the politics of representation from diverse perspectives.

It’s important to acknowledge that vast systems of knowledge and praxis have been violently oppressed and distorted by colonialism, and the work to repair that damage has barely begun. Documenta 15, with its horizontal strategies and open platforms, however perilous they may be, offers us the opportunity to be involved in real conversations about our received wisdoms, our cognitive biases, our vested interests and our positions of privilege. Those conversations will at times be uncomfortable, hurtful, and offensive. That is what deliberative democracy requires of us: an inevitably flawed struggle for an elusive, even impossible, consensus. Experimenting with the role of art within that struggle and the distribution of power within the art world is an admirable and aspirational enteprise that is being executed now, imperfectly, around the world. Documenta 15 brings some of those experiments to its audiences. It is an opportunity for dialogue about some of our time’s most important social, political and human rights challenges.

This article was amended on 29 June after publication due to a missing paragraph. New Mandala apologises for the oversight. The authors would like to thank Taring Padi for agreeing to be interviewed for this article and Dirk Tomsa for his comments on an earlier draft.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss