“Malaysia needs to be free of our dependence on fossil fuels,” said Prof Joy Pereira. It was a week after a meeting in Incheon, South Korea, where she was among climate change scientists who had huddled with government representatives from all over the world to finalise a seminal scientific report on climate change.

The report, Global Warming of 1.5°C by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), soberly lays out wide-ranging negative impacts on natural and human systems of a 1.5°C temperature rise. To stay within that limit requires carbon emissions to be cut by 45% by 2030 and zero by 2050.

The writing on the wall for Malaysia is very clear, said Prof Pereira, who was also a review editor of one of the report’s chapters.

“As a tropical country, we will experience the worst impacts in terms of extremes in temperature and precipitation, rising sea levels, food security, health and so on. Climate change is an economic issue, not an environmental one. And this decade is the only decade we have to transform.

“If we miss preventing the 1.5°C temperature increase, we are in big trouble. I know (government) negotiators have a position to hold (about cutting emissions) but the reality is that scientists are giving you a warning, and even then, it’s a conservative warning.”

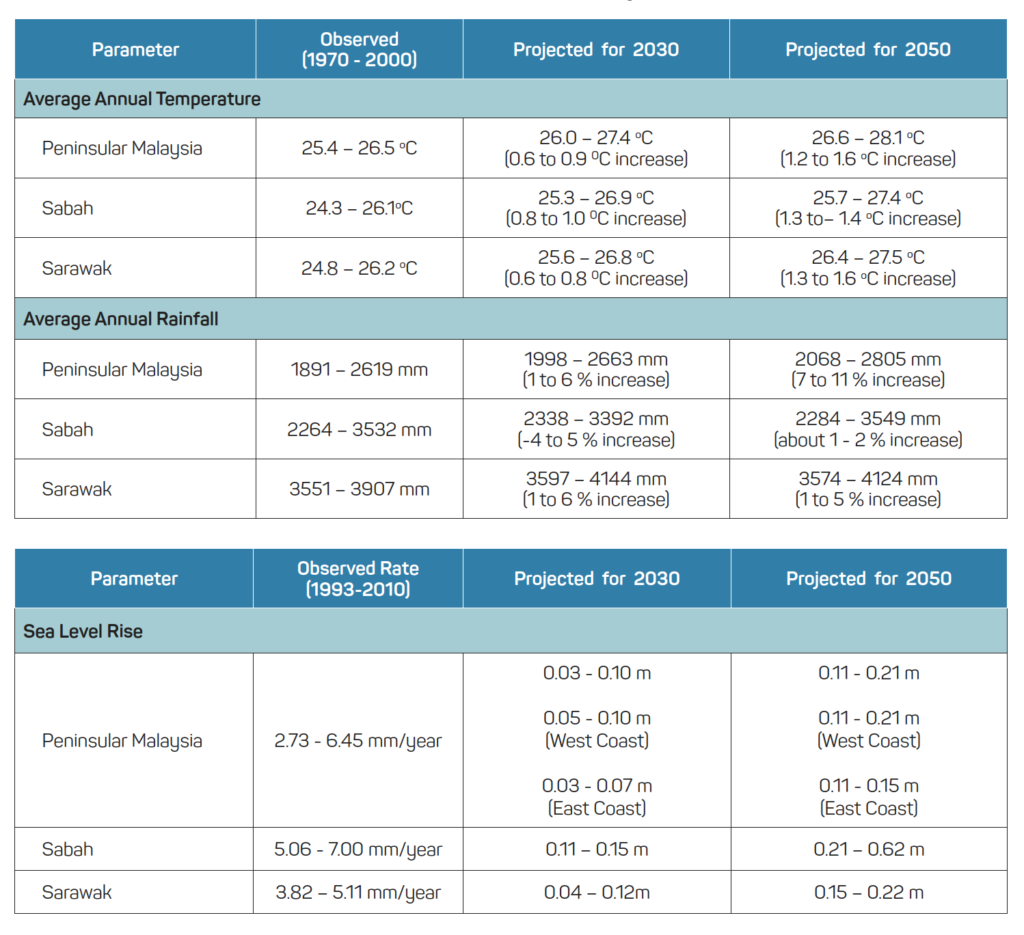

A vice-chair of the IPCC working group on impacts, adaptation and vulnerability, Prof Pereira also led the team that developed Malaysia’s National Policy on Climate Change. Malaysia’s temperature, rainfall and sea levels have all been rising in the last 40 years, and are projected to continue to do so into 2030 and beyond.

Observed and Projected Climate Change and Sea Level Rise (Malaysia – Third National Communication and Second Biennial Update Report to the UNFCCC)

The risks are already detailed in Malaysia’s latest national climate change report to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Higher temperatures risk affecting dam levels, food and commercial crop yields and livestock, including a 25% decrease in dairy production. Each El Nino period, over 40% of coral reefs, the bedrock of biodiversity and fisheries, die from bleaching due to a rise in seawater temperatures.

Floods triggered by increased frequency of heavy rain, a characteristic of climate change, could impact dam safety, rice, oil palm and aquaculture yields, infrastructure, energy supply and public health.

Meanwhile, rising sea levels intensify coastal erosion, projected in 2030 to affect 10% of the areas classified as at critical and significant erosion risks. This would impact agricultural land, infrastructure and public and private properties.

However, risk management is only a first step towards adaptation measures – responses to actual and expected climate change – and adaptation alone would be counter-productive without mitigation measures, measures that reduce the sources or enhance the sinks of greenhouse gases (GHGs).

Which brings us back to Prof Joy’s opening statement and an intriguing question. With the new Pakatan Harapan (PH) government in place, is there an opportunity to make the big change necessary to make the transition to a zero carbon future?

That climate change is being taken seriously by the PH government is borne out by the fact that it appears for the first time ever in the name of a ministry, the Ministry of Energy, Science, Technology, Environment and Climate Change (MESTECC). Its minister, Yeo Bee Yin, is a Cambridge-trained chemical engineer who is dynamic, energetic and young, among the youngest ministers in the Cabinet.

PH continues the previous Barisan Nasional (BN) government’s commitment to reduce Malaysia’s GHG emissions by 45% by 2050 relative to 2005, 10% of which is conditional upon receipt of climate finance, technology transfer and capacity building from developed countries.

In the latest national climate change report, which Yeo signed off on, it found that in 2014, a 33% reduction (or 26.8% as declared in the mid-term review of the 11th Malaysia Plan) had already been achieved, which points to the potential of hiking the target.

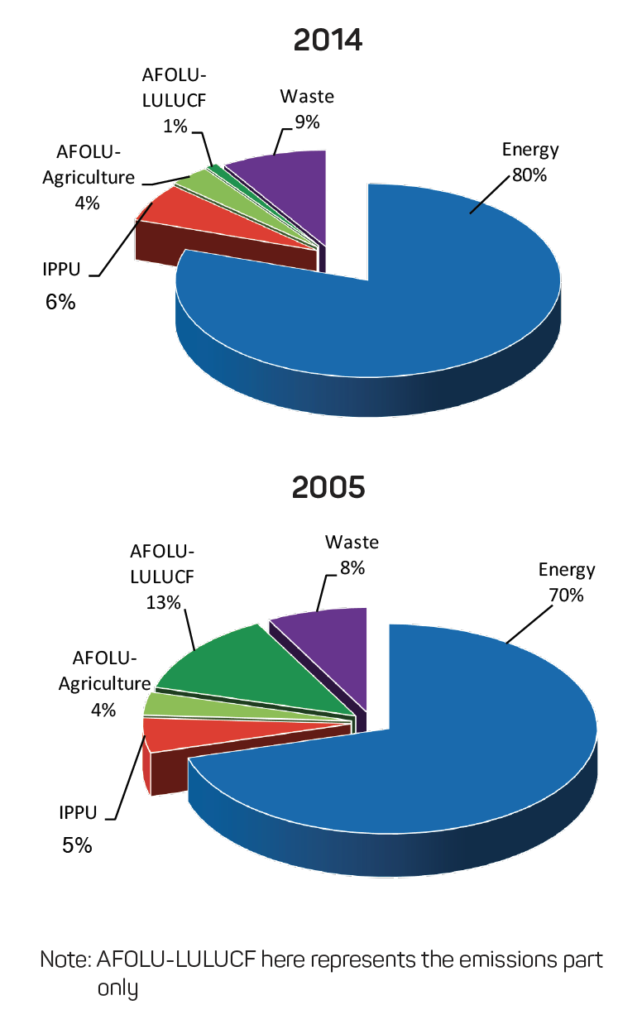

Percentages of GHG Emissions by Sector in 2005 and 2014 (Malaysia – Third National Communication and Second Biennial Update Report to the UNFCCC)

Existing strategies are robust. Climate change mitigation is focussed on reducing the five main GHG sources: the energy sector which contributed in 2014 to 80% of emissions; the waste sector 9%; industrial processes and product use sector 6%; agriculture 4%; and land use, land-use change, and forestry 1%. The approach to carbon sinks is focused on maintaining and managing a minimum of 50% of the country as forested

Meanwhile, adaptation measures prioritise the vulnerable sectors of water and coastal resources, including flood risk management; food security and agriculture; forestry and biodiversity; infrastructure; energy; and public health. The National Disaster Management Agency coordinates disaster response, guided by a multi-year strategic plan covering mitigation, preparation, response and recovery.

These points appear in varying forms and detail, even down to timelines, in a host of climate change policies, strategies and action plans. They also provide clear direction as to how to proceed, said Dr Gary Theseira, special functions officer to the new minister.

The same goes for the comprehensive reporting documents to the UNFCCC such as the National Communication and Biennial Updates. These are obligatory for Parties to the convention and are drawn up to international requirements in addition to being peer-reviewed.

“The production of these international reports requires inputs from a wide section of ministries and agencies”, said Dr Theseira. “This has brought engagement among all parties, helping us achieve greater coherence and alignment of activities.”

The PH government also continues to mainstream climate change in the 11th Malaysia Plan, the national development plan for 2016–2020. In the new government’s recent mid-term review of the Plan, environmental sustainability through green growth is maintained as one of the six policy pillars but is given a sharper focus by the streamlining of priority areas.

The strategies are laid out according to the three core climate change areas of mitigation, adaptation and risk reduction. Strategies aim to tackle the key sources of carbon dioxide emissions, which have remained unchanged from 2011: energy, transport and manufacturing. Energy in particular receives priority as it contributes to four-fifths of GHG emissions. As Malaysia’s population and economy grow, energy is also projected to continue being the main contributor to GHGs as projected up to 2050.

11th Malaysia Plan: Pillar V–Enhancing Environmental Sustainability through Green Growth (Mid-term Review of the Eleventh Malaysia Plan)

Of note in the PH government’s energy strategy is the attention to increasing the proportion of renewable energy in the energy mix, which minister Yeo in a separate announcement, said was being fast-tracked from 2% (as of 2016) to 20% by 2025. Malaysia’s primary power sources are currently heavily fossil fuel-based: natural gas, crude oil, petroleum products, coal and coke.

This means for example, that the introduction of public electric buses by the PH state governments (during BN federal rule) has actually added to GHG emissions because they are plugged into the fossil fuel-powered power grid. This needs to be kept in mind when it comes to the much talked-about ‘third national car’, transport policy revisions and indeed any ‘green’ initiative needing power from the grid.

MESTECC’s three-year programme to reform the Malaysian energy supply industry “to be green, efficient, market-based, competitive and eventually sustainable,” covers a broad range of options including increasing energy efficiency and modifying consumer demand for energy; it promises opportunities in business growth, research and development and employment.

Another priority of the 11th Malaysia Plan’s mid-term review is the foregrounding of the improvement of governance. While already in the Plan, it now holds more weight under the PH government’s overall reforming agenda.

Specifically for the green agenda, “environmental governance is fragmented and lacks coordination”. PH’s goal is to “enhance environment-related policies and legislations as well as strengthen institutional framework to ensure policy coherence and better coordination”.

For instance, under review is the high-level decision-making National Green Technology and Climate Change Council that observers say hardly met under the previous BN government. Meanwhile, MESTECC is meant to be the lead coordinating body for all things related to climate change at federal and state levels. However, natural resources (including forests which have been identified in other documents as the primary carbon sink solution) and water are under the purview of the separate Ministry of Water, Land and Natural Resources.

An environmental policy observer who requested anonymity is sceptical of MESTECC being able to play an effective coordinating role for such a large area of cross-cutting interests. “It’s still politics at the end of the day,” he said. “If the minister has a low rank as both a minister and within his or her political party, then it’s not going to work.”

He admitted it was still early days for the new PH government. But he still favoured going outside the political framework to set up an independent commission, centre or institute. This has been shown to be effective in other countries. For example, such a body could report to Parliament and advise the government on targets and policies as well as hold the federal government to account.

Still, there are encouraging signs of how MESTECC is going to proceed. Tackling plastic pollution might be ‘low-hanging fruit’ reform compared to energy reform, but minister Yeo has moved swiftly on this, something the previous government had done nothing about.

Within five months of taking office, she launched a nationwide three-phase joint-ministerial plastics roadmap till 2030 supported by the opposition states. The roadmap goes beyond reducing the use of single-use plastic bags, straws and bottles, to creating a circular plastic economy advocated by the likes of the Ellen McArthur Foundation, that will close the loop on plastics from production to consumption.

In the face of the vocal and powerful plastic manufacturers’ lobby, the road map aims to create new industries that eschew oil-based resins currently used to produce non-biodegradable plastics and move producers to cost-effective 100% biodegradable alternatives. It also aims to wean a reluctant public from not just plastics but a disposable culture, which has wider implications for waste management.

Waste is incidentally the second highest contributor to GHGs at 9%. Crucially, addressing plastic pollution is also addressing what the United Nations has declared a “planetary crisis”, that rivals climate change as a major and urgent environmental threat.

A more crucial indication of how much MESTECC might be able to achieve in climate change is how the work culture at the ministry has changed.

“We are moving from a culture of ‘I-have-to-ask-the-Minister’ to getting the right people to do the right job, and from micro-managing to letting them do the job,” said Dr Theseira, an agronomist who has been working for the government on the issue of climate change since 2005.

He added that this cultural shift was already happening to different degrees, calling it “one of the major advances in the change in government”.

“We are acknowledging that no one knows about everything. We expect technicians and experts to do their jobs, get technocrats in, good bureaucrats, people who need to understand what is going on, who push for things when they are justifiable, who know how to effect changes.”

Scientists have often been frustrated by the way government handled things, he said.

Among them is Prof Pereira, whose research has a focus on linking science to policy. She said bluntly that the role of government gatekeepers between the two needed reviewing – communication needed to be enhanced.

“This is so that we can be robust in addressing gaps. What are we asking for? Why are we asking for that? And can we do it ourselves?

“We need to move away from the rhetoric of needing to get technology transfer and lacking capacity. The previous government only wanted technology transfer. Instead, we need to provide more incentives. We have high income and local capacity, good local researchers whom we should focus on developing, a green climate fund that people should apply to.”

Capacity would need to be drawn from all groups, especially the youth.

It is telling that in the same month Yeo was appointed minister, she met with climate change civil society group the Malaysian Youth Delegation (MYD) at their request. Comprising 40 members aged 18 to 30, the group translates technical policies into relatable information for the public and holds leaders to promises made at international climate summits. They have also been representing local youth at these conferences since 2015.

MYD is asking for youth representation in the national decision-making committees. “The voices of youth are currently not strong enough,” said MYD manager Jasmin Irisha Jim Ilham. “Yet youths will be the ones facing the consequences of policies that determine the management of natural resources as well as the irreversible effects of climate change.”

At the meeting with the Minister, MYD presented their recommendations which they had also earlier forwarded to PM Mahathir’s vaunted Institutional Reforms Committee (IRC). These recommendations include greater collaboration between agencies, transparent information dissemination, and redefined agency objectives.

Jasmin is hopeful the Ministry is making the right moves. “We believe the Ministry is putting more priority on climate change, although we would like to see them walking the talk. We are also impressed that the minister is open to criticisms. For example, our stand against fossil fuel subsidies caught her attention and she addressed it directly to us as well as in a separate interview with the South China Morning Post.”

The IPCC report states that the world has already breached a 1°C temperature increase. Overshooting the 1.5°C by another half a degree to 2°C would see disproportionately more severe impacts and require even more drastic action. For example, at 2°C, extreme heat would be 2.6 times worse, coral reef degradation 29% worse and flood risk 170% higher.

Rapid and far-reaching transitions in systems are needed, it said, transitions that are “unprecedented in terms of scale, but not necessarily in terms of speed, and imply deep emissions reductions in all sectors, a wide portfolio of mitigation options and a significant upscaling of investments in those options”.

Prof Pereira suggested that such unprecedented action for Malaysia might include transitioning the national energy giant Petronas from extracting oil to capturing carbon. But for the time being, “green growth is already mainstreamed. It now needs to be operationalised.

“Our government can put in policies to get the private sector to mobilise, technical agencies to rise to the challenge, people to change their lifestyles. For at the end of the day, we all want the same thing: prosperity, a good life, a planet for our children.”

References:

Joshi, D. 2018. “Electric Vehicles in Malaysia? Hold Your Horsepower!”, Kuala Lumpur: Penang Institute.

Ministry of Economic Affairs (2018). Mid-term Review of the Eleventh Malaysia Plan 2016-2020—New Priorities and Emphases.

Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment Malaysia (2010). Dasar Perubahan Iklim Negara | National Policy On Climate Change. Malaysia: Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment Malaysia.

Ministry of Energy, Science, Technology, Environment and Climate Change Malaysia (2018). Malaysia – Third National Communication and Second Biennial Update Report to the UNFCCC. Malaysia: Ministry of Energy, Science, Technology, Environment and Climate Change Malaysia.

National Disaster Management Agency (2017). Disaster Management in Malaysia. Malaysia: National Disaster Management Agency.

Pakatan Harapan (2018). Buku Harapan – Rebuilding Our Nation Fulfilling Our Hopes. Malaysia: Pakatan Harapan.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss