Part 3: “Milestones” (Concluded)

An Evening at IKIM

But, despite the collapse of Rashad Khalifa’s position and the ignominious murder of its author, it was not quite the end of the matter.

Several years later, some time in the early 1990s, Kassim Ahmad received some high-level encouragement to open up once more the debate about hadith and, by implication, the role, including the special position and claims to special authority, of the ulama as a group or “clerical estate” in Islam generally and specifically in modernising Muslim societies such as Malaysia.

The congruence or “fit” between these ideas, if they were sustainable, and those of Prime Minister Dr. Mahathir is obvious.

Dr. Mahathir’s core initiative was to emphasise Islam, modernisation, and, as part of the same overall cultural complex or “package”, modern understandings of Islam. If the resistance to him and his, and the UMNO’s, religious “project” came from the religious traditionalists and their allies, deeply entrenched not only within PAS but also the UMNO itself, then an argument that might decisively defeat and delegitimise that clericalist opposition was, it seems, worth considering.

Anything that would put his traditionalist and traditionalising Islamist adversaries on the defensive, and possibly seize the political initiative from them, was worth a try. So the hadith controversy had, was allowed, a brief second life.

At a political moment when these issues were very much in the air, and prominent in the minds of some leading Malaysians, it was decided that the hadith question with its related, and to some very troubling, implications about “the special position of the ulama in Islam” might have a another hearing: not the trench and guerrilla warfare of the original UKM confrontation but something more dignified and also controlled –– from above, rather than by unruly dissenting academics.

Accordingly it was arranged that a public forum would be held under impeccable auspices, and that it would be taped for later broadcasting, in edited form, via national television on RTM1’s long-running and very popular Thursday evening religious programme Forum Perdana Hal Ehwal Islam.

The event itself was staged in the elegant public auditorium of the then quite newly established and salubriously housed government entity IKIM: Institut Kefahaman Islam or Institute of Islamic Understanding.

A so-called “think-tank”, it was yet another of those handsomely funded institutions that Prime Minister Dr. Mahathir created to develop an alternative Islamic agenda and project a rival Islamic worldview to those of PAS and the clericalist traditionalists –– but which in the end, because they were placed under the leadership of people who simply did not understand with sufficient cultural and historical depth what the task and challenge facing them were, never had any possibility of addressing them successfully.

The people placed in charge of these wondrous new creations were simply intellectually inadequate to the challenge they faced, they lacked the deeply grounded knowledge even to grasp what was involved, let alone take on that challenge and see the task through to successful completion.

They never knew and understood what they had to know and understand if they were to accomplish, or even plausibly begin, the historic task that was expected of them, So, in the end, these institutions, including the Islamic University [UIA/IIU] and others too, fell by default into other hands. They ended up being “gifted” by Dr. Mahathir’s government as resources to the very forces that their creation had been intended to oppose and contest.

Yet these were early days for IKIM and for Dr. Mahathir’s hopes of it. The forum was organised. Kassim Ahmad had the chance to state his case, as did two notable and knowledgeable opponents. After their presentations and some direct exchanges, amounting to a tough and quite hostile cross-examination of Kassim Ahmad by his critics, the forum was opened up, in accordance with the Forum Perdana Islam format, to questions and comments from the floor.

Eventually I took the opportunity to make a point. I decided to refer to and then quote some lines from the work of the great Pakistani/Canadian Islamic scholar, the late Professor Fazlur Rahman who, perhaps more than any other individual in the twentieth century, had sought, with some considerable success, to bridge, as a pious Muslim, the worlds of classical Islamic scholarship and the modern academic study of the Islamic tradition.

By doing so I sought, after the torrid cross-examination of Kassim Ahmad, to restate the same position in different words, now with the backing, prestige and authority, grounded within the Islamic tradition, of a truly great scholar and moral leader.

I referred to Prof. Fazlur Rahman’s Islamic Methodology in History (1965) and then to his Islam and Modernity: Transformation of an Intellectual Tradition (1982).

These are two landmark studies –– milestones, one might even say, or perhaps better, benchmarks –– of Islamic modernism and modernist Islam at their highest point. In the latter work, Fazlur Rahman remarks that the

“proliferation of hadiths resulted in the cessation of an orderly growth in legal thought in particular and in religious thought in general” [26]; as a result, “it came to pass that a vibrant and revolutionary religious document like the Qur’an was buried under the debris of grammar and rhetoric. Ironically, the Qur’an was never taught by itself, most probably through the fear that a meaningful study of the Qur’an by itself might upset the status quo, not only educational and theological, but social as well” [36].

To help, or rather begin, addressing the problems created by this proliferation of often dubious hadith and the effect that a long traditions of sophistic hadith scholarship had had for the study of the Qur’an itself, Prof. Fazlur averred that

“the first essential step … is for the Muslim to distinguish clearly between normative Islam and historical Islam [141]. To do so, “we must make a thorough study, a historically systematic study, of the development of Islamic disciplines. This has to be primarily a critical study that will show us … the career of Islam at the hands of Muslims … the need for a critical study of our intellectual Islamic past is ever more urgent because, owing to a peculiar psychological complex we have developed vis-├а-vis the West, we have come to defend that past as though it were our God. Our sensitivities to the various parts or aspects of this past, of course, differ, although almost all of it has become generally sacred to us. The greatest sensitivity surrounds the Hadith, although it is generally accepted that, except the Qur’an, all else is liable to the corrupting hand of history. Indeed, a critique of Hadith should not only remove a big mental block but should promote fresh thinking about Islam” [147].

“A historical critique of theological developments in Islam,” Prof. Fazlur added, “is the first step towards a reconstruction of Islamic theology [151]. This critique … should reveal the extent of the dislocation between the world view of the Qur’an and various schools of theological speculation in Islam and point the way to a new theology” [151-152].

Having alluded generally to Prof. Fazlur Rahman’s career and ideas, I cited explicitly his words that “the greatest sensitivity surrounds the Hadith, although it is generally accepted that, except the Qur’an, all else is liable to the corrupting hand of history. Indeed, a critique of Hadith should not only remove a big mental block but should promote fresh thinking about Islam.” I then posed the question to the more outspoken of Kassim Ahmad’s two critical interlocutors on the Forum Perdana panel how he responded, in this present context, to Prof. Fazlur’s principled and informed position.

When challenged to address himself to these words from Fazlur Rahman (which in essence, if far more diplomatically, stated a position similar to that of Kassim Ahmad), Dr. Othman al-Muhammady responded very precisely that, in his view, “Fazlur Rahman had been a great man in the history of Islam, but his aqidah [the integrity of his faith] was questionable and his influence had been damaging and remained dangerous”.

Aftermath

It remains only to note three things.

First, that Dr. Othman al-Muhammady was one of the featured speakers, perhaps the central speaker, at the Muslim Professional Forum’s symposium in September 2005 that targeted “Liberal Islam: A Clear and Present Danger”.

Second, that, with those legally resonant words in that subtitle, the symposium was branding modernist Muslims and the proponents of Islamic modernism as promoters of sedition and treason.

And third, that at the same time when Dr. Othman al-Muhammady was acting as the guiding spirit and prime mover of the onslaught upon liberal Islam as “a clear and present danger”, he was appointed to serve as a Commissioner of Suhakam, the official, statutory Malaysian Human Rights Commission of the government of Malaysia.

What are people, including those of the Fazlur Rahman intellectual “lineage” and scholarly tradition in Islam, to make of this bizarre appointment and the thinking behind it? Who knows? Many may simply remark, in a formula of conventional piety, “WaAllahu’alam …”, that only God truly knows, knows the truth. The Truth is ever with Allah.

Here on earth, meanwhile, one may suggest that the brutal verdict which Dr. Othman al-Muhammady was happy to place upon Fazlur Rahman –– against the integrity and grounding of his faith, and scorning his influence upon and place in modern Islamic intellectual history –– offers a very telling insight into the meanness, the vindictive nature, of the emblematic leaders of the “new Islamism” when they find themselves cornered and effectively challenged.

Meanwhile, though the Truth may be with God alone, as mere humans those of that modernist tradition may and should endeavour –– since it is a truly wondrous and wonderful part of their fitrah or divinely created human ontology –– to use in good faith their human power of reason, always, of course, in well-guided ways.

What does well-guided mean?

The question is whether people may, in good faith and reason, seek out and seek to combine wisdom from a variety of sources. Or whether, when matters are contested –– which is when they truly matter –– there is one sole and unique source of guidance to which believers must turn and whose admonitions, almost always of a restrictive nature and intention, all must accept as authoritative: the guidance ever so insistently proffered by the exclusivist and exclusionary clericalist monopoly.

Which choice people should make is not for me to say. I simply note that the choice is theirs and that it is there. Of those who would deny that fact, and seek to deny others that choice, one may simply, and legitimately, ask that they clarify their motives and intended agenda.

Postscript

For the record, Dr. Othman al-Muhammady died in early 2013. But his ideas and influence are far from dead. Very recently I saw in the Malay press a column praising him and his work that was written by Senator Dato Dr. Mashitah Ibrahim, an Islamic International University doctoral graduate in Islamic Studies who is a Deputy Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department. In the context of delivering her praise, she noted that a book honouring Dr. Othman al-Muhammady and his work has recently been launched by the Deputy Prime Minister (“Inteligensia Muslim kontemporari,” Sinar Harian, 1 August 2014).[1]

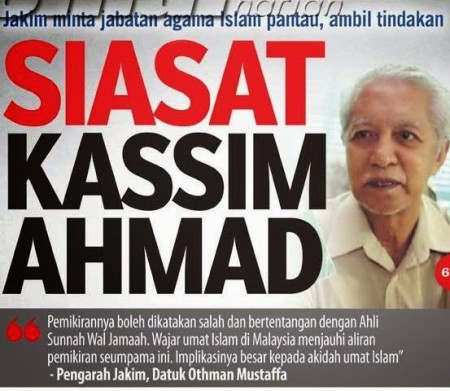

And meanwhile, as Kassim Ahmad is dragged out of his house and into police stations in the dark morning hours and dragged through the courts, it is clear that even in the year 2014 his story is not yet over.

So long as he lives, as his will lives, I dare say, he will not let it end.

Beyond his own story of lonely determination, the issues that he and the official treatment of him raise will not go away.

They are of the highest importance.

As with al-Hallaj –– but now in very different and supposedly far more advanced times –– they involve the nature of religious faith, thinking and reason and the rights of citizens to live their own lives in their own heads, free from being bothered by government officialdom, and to talk to their fellow citizens about their ideas.

Ultimately, at stake here is the question of a triple freedom: freedom of religion, freedom from religion, and also freedom in religion.

Parts 1 and 2 are available HERE and HERE

[1]http://www.sinarharian.com.my/kolumnis/inteligensia-muslim-kontemporari-1.303862 Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss