An exercise in extending absentee suffrage for Myanmar’s citizens abroad.

The 2015 election in Myanmar marked a major milestone in the country’s political transition and return to democracy. But some people were left out of the historic vote.

The reasons to not allow an individual to vote are as much a part of the history of all our great liberal democracies as they are a continual reminder to remain vigilant for those of us who may have lost that right somehow. In the past, some of us did not own property, were not the right kind of ‘white’ (Northern European), were not men, a tad too tanned or rather much too noir, or simply too young to vote — yet not too young to make the ultimate sacrifice in “foreign war.”

If the above reflects too much of the Western experience, then one could also include reasons like class, religion or lack of, language or dialect, caste, cult, ideology, marriage status, education level, sexual preference, and on and on.

Think of some ridiculous social cleavage, some cultural hang-up of yesteryear, and the astute comparative political scientist will ultimately be able to pluck another tawdry example from an even more exotic, backward republic. Give the polity an election and it will collectively vomit out some new excuse for democratic exclusion come election day.

But how does one analyse the individual who once had a political right and has now lost it? How about the individual who lost the right to vote for no reason other than not being at the right place at the right time on election day? A loss on grounds of a technicality—of logistics?

In Myanmar’s 2015 election, they had a constitutional mechanism ready to thwart such a possibility. In the 2010 House of Representatives Election Law, a provision exists in Chapter IX, section 45 to 47, which allows for an “advance ballot.” This is meant to assist those citizens who are bedridden, who may be out of the township on business, or who may be even so far away as to be beyond the territorial sovereignty of the state. Though what is legislated through Parliament and what is effected via on-the-ground operations, alas, proved to be very different.

Of those who were registered to vote on 8 November 2015 turnout was reported at 69 per cent. Yet, those were domestic voters. How about absentee voters? Those who used “advance ballots” to vote from abroad?

In total, the Burmese diaspora is often estimated at around 10 per cent of the total 51 million currently residing in Myanmar— about 5.1 million. Exact numbers are not reported by the Union Election Commission of Myanmar (nor were they willing to give me those exact numbers after repeated requests), but we do know that something like less than 20,000 Burmese abroad actually voted externally leading up to election day.

Even if we generously discount half of that 5.1 million as being ineligible because of age or some other mitigating factor, this would still mean that turnout for the absentee vote did not reach more than around 0.7 per cent. Thus, we are left comparing 69 per cent turnout domestically with 0.7 per cent turnout from abroad.

Two questions immediately present themselves. The first is for whom or for which party exactly would these absentee voters have voted if given a real opportunity to do so? The second is, after analysing these potential what-if votes, was there a lost opportunity for the challenger political party National League for Democracy (NLD), or for the “old regime” party United Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), or for both?

The number of migrants, expats, refugees, and “other” from Myanmar currently in Thailand is often estimated at between 2 to 4 million people. Let’s use 2.6 million Burmese in Thailand as a conservative estimate. Reviewing whom the Burmese economic and political émigrés might have voted for if provided a logistical and legal option to do so makes for a fascinating counterfactual study. And beyond the purely scholarly, it should also be a wakeup call for potential party canvassers for the 2020 election—whether they be NLD, USDP, or one of the many “ethnic”-based parties.

So on to the question of who would you have voted if given the chance. The only data that exists for this potential what-if set of external voters can be found online. Early analysis yields interesting results.

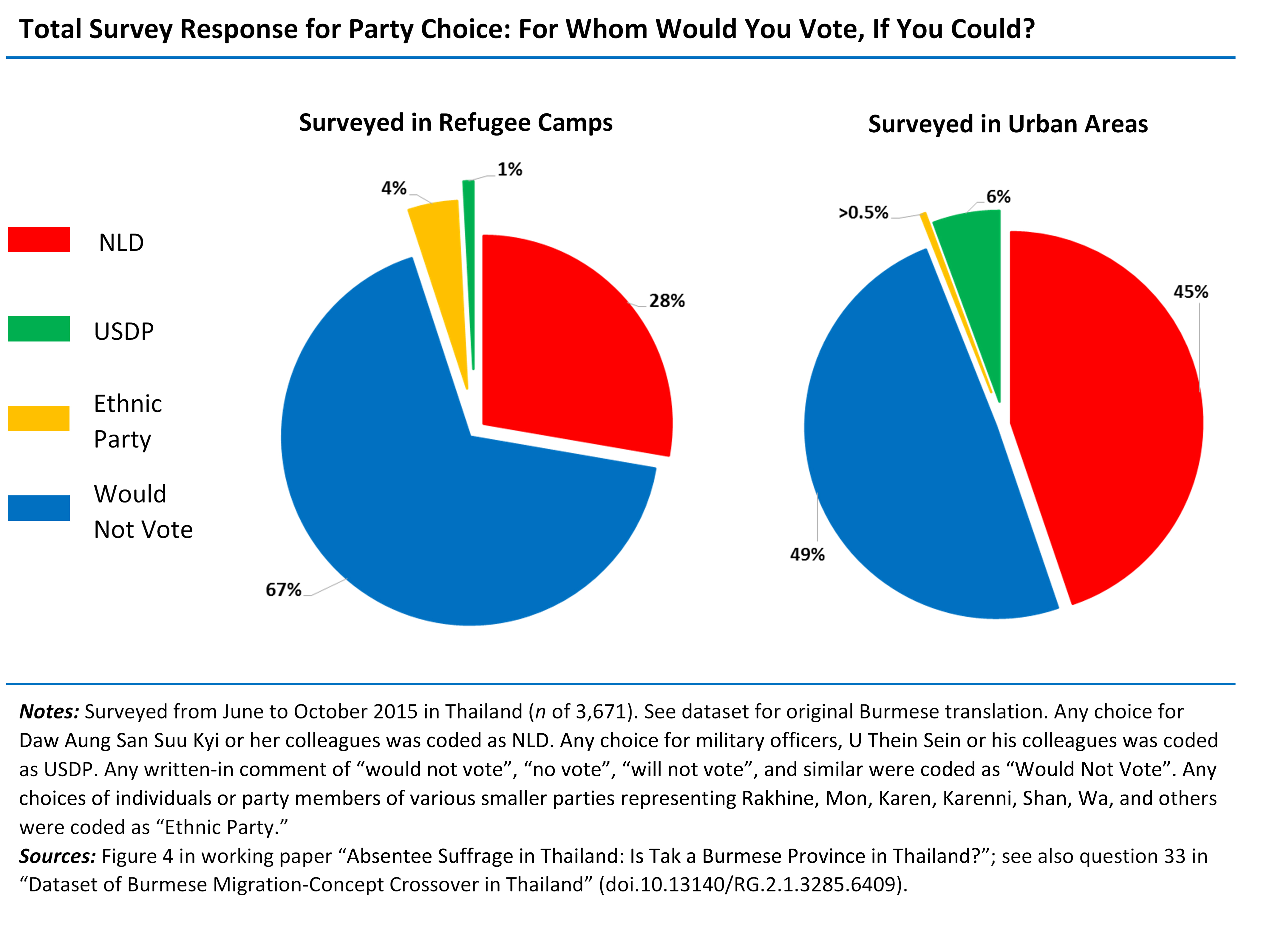

Some early surprises among this what-if absentee voter population is how little demographics (age, sex, ethnicity, religion) and partisan politics in general seem to affect how one would vote. Instead, the more salient predictor variables depend on mobile location (living in a refugee camp or urban area), mobile self-identity (refugee, migrant labourer, other), past persecution under former Burmese regimes (corruption, forced labour, threats, actual violence, fear of return), and the level of “democratic support” (livelihood vs voting rights). These cannot all be presented here, but the figure below provides at least one of the descriptive findings of the study.

What we can immediately see, and in fact would probably expect, is that the population of migrants who live inside one of the nine “refugee” camps in Thailand do not have the same voter preference for the population of migrants living either in an urban area or near one of the countless factories lining the Myanmar-Thailand border.

Another quick finding is how many of these émigrés, despite being given the hypothetical question, simply choose the “Would Not Vote” option. An honest assessment of this trend may simply reflect would-be voter disillusionment of the fact that in the 2015 election 25 per cent of both the upper and lower seats in Parliament were automatically reserved for active military men.

Regardless, this no-vote makes for an intriguing base-line category from which to do a more robust study in terms of odds ratio. It also makes for an interesting way of clarifying probabilities of not only what-if voters, but also likely would-be voters if absentee suffrage were to be extended to them. In other words, we can calculate what the likelihood is of either a refugee migrant or labour migrant opting for NLD over no-vote, or USDP over no-vote, or any ethnic party over not voting at all.

The results of such an analysis argue that, for those self-identify themselves as “labour migrants”, they are 57 per cent more likely to vote for NLD over not voting at all. As for those who self-identify themselves as “refugees”, they are 10 per cent less likely to vote for NLD over not voting, and 77 per cent less likely to vote for the “old regime” USDP over not voting at all .

What may be more interesting here is to report that a working draft of these findings was recently shown and explained to Burmese migrant labour activists, former political prisoners, and refugees in camps on the Thai side of the border. This opportunity for re-interview and participant review generated a consistent response from all those migrants from Myanmar in Thailand, regardless of their mobile self-identity, their political affiliation, or whether they even value the right to vote abroad or not.

All could identity something of a “lost opportunity” for the 2015 election in Myanmar. As one participant who actively canvased for the NLD in her hometown put it, despite being an “illegal” Burmese émigré living in Bangkok at the time and thus not being able to vote herself:

“We need to make sure that all the migrant labourers have an easier way to participate in the next general election. This will mean that the Burmese embassy staff will need to understand how to set up a polling station for all of us here. And we will have to have special polling stations across major Burmese migrant towns, in Bangkok, in southern Thailand, and along the border. This will have to be tied to some mechanism for timely voter registration in home townships.”

Indeed, an open letter from the migrant associations operating in Bangkok to Daw Aung San Suu Kyi during her official June 2016 visit to Thailand included not only recommendations about labour rights for migrants but also recommendations about the political rights of Burmese in Thailand for future national elections. Though Daw Aung San Suu Kyi did not end up publically addressing the absentee suffrage issue during her visit, the fact that politically active Burmese in Thailand included this in their letter already demonstrates their concern with “not losing this opportunity again” for potential external votes to be counted in the next general election.

Though most of the heart-felt media attention fell on those usually-reported minority groups of ethnicity or religion who may have been unable to vote in the 2015 election, we would do well to remember that these minority groups do not even began to reach the number of millions of Burmese abroad who were left out of the vote.

Regardless of the reason for moving beyond the territorial boundaries of Myanmar, these migrants, labourers, expatriates, refugees, former political prisoners, students, émigrés and other in total could have a profound effect on the next general election if absentee suffrage were extended to them equally.

TF Rhoden is a PhD candidate at Northern Illinois University. The working paper “Absentee Suffrage in Thailand: Is Tak a Burmese Province in Thailand?” will be presented for the first time publically at Le Meridien Bangkok Hotel, Surawongse, Bangkok on 28 July 2016. Those in Bangkok are urged to come and participate!

This research project is funded in part by Chulalongkorn University’s 2016 Empowering Network for International Thai Studies (ENITS) fellowship.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss