New Mandala’s excellent coverage of the Indonesian elections has highlighted the importance of the discourse of “vote buying” in relation to Southeast Asian politics. As long-time readers of New Mandala will know, I have never been comfortable with the term “vote buying” and the common tendency to conflate the distribution of cash prior to elections with the “purchase” of votes.

Here are some notes on “vote buying” that I prepared some time ago, which question the usefulness of the term. My point of reference is Thailand, but the implications of the argument are broader.

***

In order to understand the role of vote buying in rural political society, I want to turn to an important distinction made by anthropologists between commodities and gifts.

In relation to commodity exchange, James Carrier writes that “At their simplest, commodity transactions consist of a transfer of value and a counter transfer: the transfer of an object or service from A to B and the counter transfer of money from B to A. In other words, A sells something to B.” This is the model of exchange implied by the term “vote buying”: voters provide a valued “service”, their vote, in return for a “counter transfer of money.”

However, as those who analyse vote buying regularly note there is a fundamental problem in this model: how does the purchaser ensure that the “commodity” or “service” is actually provided, especially in the increasingly common context of a secret ballot?

Various solutions are proposed to this “compliance problem”: directly observing voters as they cast their votes; asking voters to produce mobile phone photos of their ballots; encouraging voters to believe that their votes can be checked (even if they cannot); localising the counting of votes to make it easier to check purchases against actual votes cast; and playing upon values of trust, reciprocity or patronage to maximise adherence to the vote-buying contract. Alternatively supporters of opposing candidates may be paid not to vote.

However these commodity exchange enforcement strategies involve substantial costs, especially when there are a number of “buyers” competing in the electoral market place.

International studies of vote-buying suggest that the compliance problem is most commonly addressed by embedding the transaction within dense networks of social exchange. This is generally achieved through using local vote canvassers to make the “purchases.”

These canvassers are responsible for a relatively small number of electors; they usually have strong social, political and economic links with the community of electors; they are in a position to interact on a regular basis with the vote “sellers”; and they can build up enduring feelings of obligation, indebtedness and reciprocity.

In other words, vote buying is socially embedded.

As a result of this social embedding, vote buying starts to look less like the purchase of a commodity and much more like the exchange of gifts. Carrier expresses this important distinction in the following terms:

Gift transactions resemble commodity transactions in that they consist of a transfer and a counter-transfer. And also like commodity transactions, the counter-transfer can take place at the same time as the transfer or it can be delayed. What makes such a transfer a gift transaction is the relationship that links transactors to each other to the the object they transact. In gift transactions objects are not alienated from the transactors. Instead, the object given continues to be identified with the giver and indeed continues to be identified with the transaction itself.

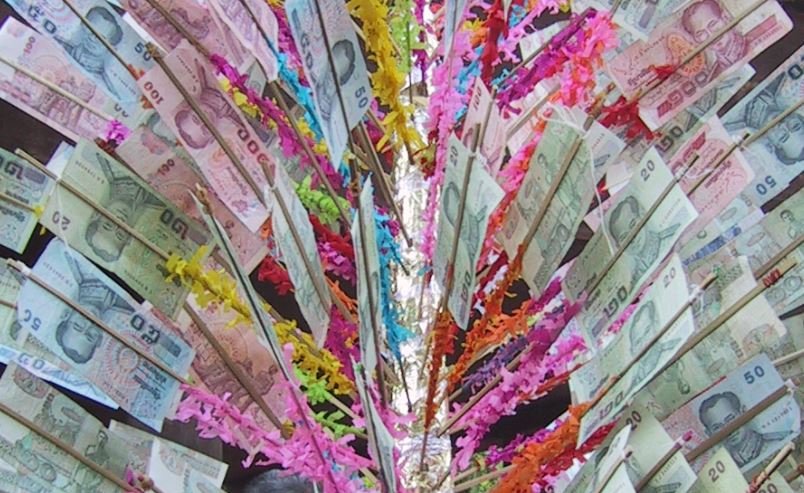

It is a mistake to assume that the presence of money marks a transaction as commodity exchange. Money can play an important role in gift exchange, often taking on social meanings that extend well beyond the commodity value of the notes or coins involved. This is all too evident in Thailand in the elaborate and conspicuous ways in which money is used to signal enduring relationships at temple festivals, weddings and funerals.

Cash transacted in gift exchanges becomes a form of “special money” that, while clearly fungible, remains bound up with the identity and intentions of the giver. By stapling their campaign brochures to 100 baht notes, political candidates in Thailand are attempting to merge their personal identities with the symbolic, rather than purely financial, power of money.

So, what are the implications of viewing “vote buying” as type of gift exchange or, more precisely, as an attempt to establish a gift relationship? What is the role of this particular form of gift exchange in Thailand’s middle-income rural economy? I address these questions by focusing on three related dimensions: meaning, personalisation and evaluation.

The meaning of development

What does the distribution of cash prior to elections mean in Thailand’s modern rural society? In general terms, it symbolises a willingness and ability on the part of political candidates to promote local development. In a rural economy that has become strongly dependant on state support, development has become a dominant political value.

In rural political contexts a standard mode of justifying or challenging a candidate’s credentials is the extent to which he or she has, or will, bring development to the local area. The importance of this value is reflected in the ubiquity of terms such as phattana (development), charoen (prosperity), and kaaw na (moving forward) in local campaign material.

The discursive force of ‘‘development’’ in electoral culture is complex. On the one hand it fits readily with the image of the generous and good-hearted patron who makes personal sacrifice for the benefit of the broader community. Financial donation prior to the election is a demonstration of the candidate’s willingness and capability to direct development resources to constituents. Personal sacrifice and community development are linked symbolically.

But, at the same time, a distinction is emerging in local political discourse between forms of benevolent assistance that are expressed in personalised patron-client terms and forms of development assistance that are linked to more socially inclusive modernist discourses of progress, administration and broad-based access. Whereas personal generosity is valued highly in relation to the former, the latter places primary emphasis on the ability to mobilise government resources effectively and to direct them to ‘‘projects’’ in the local area.

This latter, more modernist, orientation does not regard the distribution of cash as inappropriate, but it does generate an expectation that gifts of cash are part of a broader political program of improvement in infrastructure, services and livelihood projects. As Callahan and McCargo note, “despite the importance of money in the July 1995 Thai election campaign, there was more to being elected than spending money, legally or illegally. Successful candidates, particularly incumbents or former MPs, had to campaign on the basis of their phonngan (achievements).

Personalisation and political society

Treating the distribution of cash prior to elections as an attempt to establish gift relationships also draws attention to the extent to which the political process has become personalised and socially embedded in modern rural Thailand. One of the enduring motifs of an earlier generation of studies of rural politics is the disengagement of the peasantry from the political process. The mass of the peasantry were remotely and passively connected to national politics via a national hierarchy patron-client relationships. This generated what Stephen Young famously described as a “non-participatory democracy” in which peasants expected to have minimal involvement with government and acknowledged that powerful people should be obeyed. In such a system active political engagement in rural society was confined to leaders, such as headmen, monks and businessmen, who acted as brokers between the mass of the population and government agencies.

At one level, vote buying as gift exchange fits well within this established patron-client model: the patron-politician provides a gift of cash in return for the reciprocal support of the politically passive client-voter. However, the modernisation of the rural economy and its incorporation into a convoluted web of administrative networks has made the social dynamics of this gift exchange much more complicated.

The economic diversification of the countryside has reconfigured old patron-client ties. The spatially and economically dispersed livelihood strategies pursued by most peasant households mean that all-encompassing ties with a single patron are much less common. Connections with economically influential figures remain important, but the modern proliferation of economic and administrative power means that such linkages are now components in a much more complex network of livelihood security.

In Thailand’s Political Peasants (Walker 2012), I describe this personalisation as being a central feature of rural Thailand’s new “political society.” Taking inspiration from Partha Chatterjee’s work on subaltern politics in India, I suggest that rural politics in Thailand can be more usefully understood by focussing on the informal networks of political society rather than the formal non-government associations of civil society. Political society in rural Thailand can be understood as being made up of a vast network of relationships through which people attempt to favourably influence the distribution and flow of power and resources.

Connections in political society are predominantly interpersonal rather than associational. They blur the distinction between the public and private sphere, relying on a process of disaggregation and domestication that draws politicians and officials into personal relationships, local ritual cycles and an enormous variety of development projects. Whereas the iconic event of civil society is the public meeting, political society constructs a more intimate sociality built around meals, gift-giving and festivals. Political society’s lessons about democracy are not learnt in associational “schools” but in day-to-day interactions with mundane forms of government. Political society’s connections are also highly diverse, linking rural people to government agencies, private enterprises, local power-brokers and a rich panoply of supernatural entities. This is the politics of diversity and complexity. In the world of political society, benefits flow primarily from connections, manipulation, calculation, and expediency, not from the universal rights of modern citizenship as envisaged by most civil society movements.

Rural Thailand’s new political society resembles what, in China, the anthropologist Mayfair Mei-Hui Yang called a “gift economy” in which “social relationships and obligations … are immediate and revisable, contingent upon personal circumstances and specific power situations.” The distribution of cash is one of the ways in which the personalisation of political relationships in this new political society is marked.

Evaluation and the “rural constitution”

A third important implication of viewing “vote buying” as an attempt to create a gift relationship is that it highlights the importance of systems of evaluation. Studies of vote buying regularly show that it is often unsuccessful. As Shaffer writes about vote buying in the Philippines “most voters who received money still apparently exercised their freedom of choice.” And Wang notes that the system is imperfect in Taiwan, even when vote buying efforts are well resourced and intricately organised: “The system was imperfect – a considerable portion of the electorate failed to vote for the Kuomintang after selling the votes to the party.” This high rate of failure occurs even in contexts where vote buying is accompanied by various forms of electoral intimidation. Consider Bratton’s observations from Nigeria:

Importantly, the available evidence suggests that vote buying and political intimidation are ineffective campaign practices. In reality, people who are paid or threatened during the election campaign are actually less likely to turn out to vote on polling day. Threats of violence lead to an especially sharp reduction in voter turnout. Moreover, while voters may be willing to cast their ballots for parties whose candidates have broken electoral laws, many would have expressed such support anyway, that is, without extra-legal incentives or punishments. Most importantly, many who enter vote-buying agreements say that they will ultimately defect, that is, by taking the money but voting as they please. Defection is especially likely when voters are cross-pressured from both sides of a partisan divide or when exposed to both vote buying and violence.

One of the main reasons that “vote buying” fails is that the attempt to create a gift relationship is subject to voters’ evaluation and, as such, is often rejected. When a commodity is sold a system of evaluation is present, but it is narrowly based, focussing principally on the price.

However in gift exchange a more wide-ranging set of criteria are drawn upon. In the Thai context, I refer to this broad framework of electoral evaluation as a “rural constitution.” The regulatory object of the rural constitution is not the formal political system but the extensive network of relationships that makes up modern rural society’s new political society. The rural constitution is an uncodified set of values that is based on the desirability of embedding political and administrative power into local networks of exchange and evaluation.

The pre-election distribution of cash by politicians falls under the informal jurisdiction of this rural constitution in several ways. First, cash payments that are not embedded in local social networks will not be regarded as credible. They will be accepted, but are unlikely to generate reciprocal action in the form of voter support. Political candidates need to be able to demonstrate that they have meaningful links with their constituency either through family connections, business dealings or, most importantly, a record of contributing to local development. This “localism” is not the self-sufficient localism promoted by some NGOs: locally embedded political representatives are not valued because they embody local resources or capabilities but because they are more likely to direct externally derived resources to locally valued initiatives. They are culturally and socially familiar figures with whom villagers feel relatively confident to negotiate for material benefits. If it is carried out correctly, distribution of cash can contribute to this localist familiarity.

Second, it is important that the distribution of cash reinforces a sense of personal sacrifice on the part of the political candidate. Sacrifice (sia sala) is an important value in the rural constitution. In idealised terms it typically involves the diversion of some resources (labour, time and cash) from the political candidate’s private affairs to the public sphere through activities such as participating in committees, assisting with the implementation of development projects, making representations on behalf of less capable villagers, and active involvement in village festivals. Provision of financial assistance is a highly visible way of demonstrating personal sacrifice, especially in the busy pre-election environment when time constraints limit other forms of participation.

Third, the distribution of cash is subject to local evaluations of corrupt behaviour. Contrary to stereotypes of rural nonchalance about corruption, discussions about the inappropriate use and diversion of money are a ubiquitous feature of local political life. Where the distribution of cash is regarded as being insufficiently socially embedded–that is, where the candidate’s local connections and record of personal sacrifice are weak–it may be regarded as corrupt. Candidates who spend heavily on mobilising votes, but who perform poorly against the various evaluative provisions of the rural constitution are likely to attract some degree of condemnation. Voters are likely to accept their “payment”–rejecting the notion that is a socially embedded gift–and then default on the provision of the commodity, their vote.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss