The data shows that violence in Thailand’s intractable insurgency is on the decline. But is that set to change?

While many in the junta continue to point fingers at the Red Shirts for, what are now being called the Mother’s Day Bombings, the forensic evidence is pointing to southern Malay insurgents, led by the Barisan Revolusi Nasional (BRN).

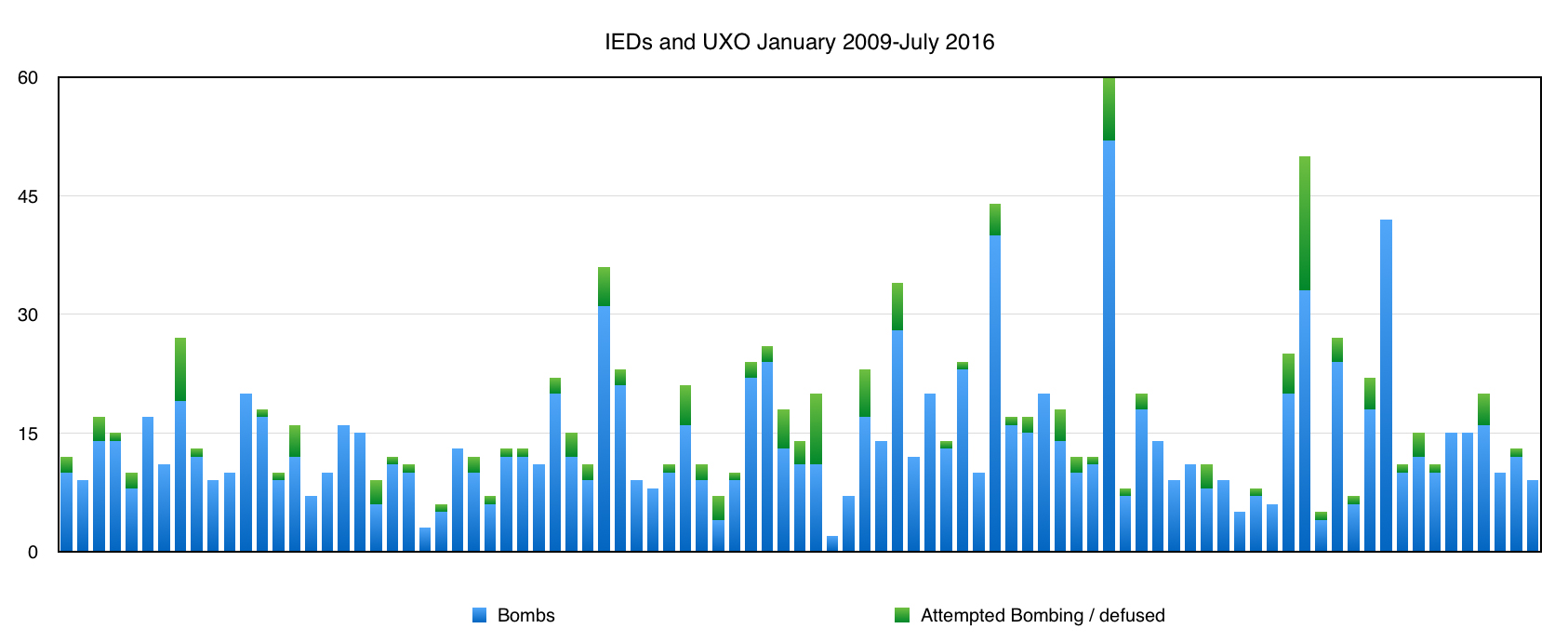

In all, there were at least 20 IEDs between 10 and 14 August that struck Thailand’s upper south. At least five failed to go off or were defused. Many of them were incendiary devices made from alcohol fuel gel and matches, packed into cell phones and external chargers. The devices killed four people and wounded 30, including 10 foreigners.

While many pointed to the fact that so many of the attacks had two devices, these were not what are commonly referred to as a “double tap.” A real double tap, occurred in Narathiwat, on 15 August, when a 20kg IED targeted a group of marines on patrol wounding two; the second IED went off 10 minutes later to target the first responders. Those bombings in Narathiwat, followed three other small attacks in Yala over the weekend, with two additional devices that failed to go off.

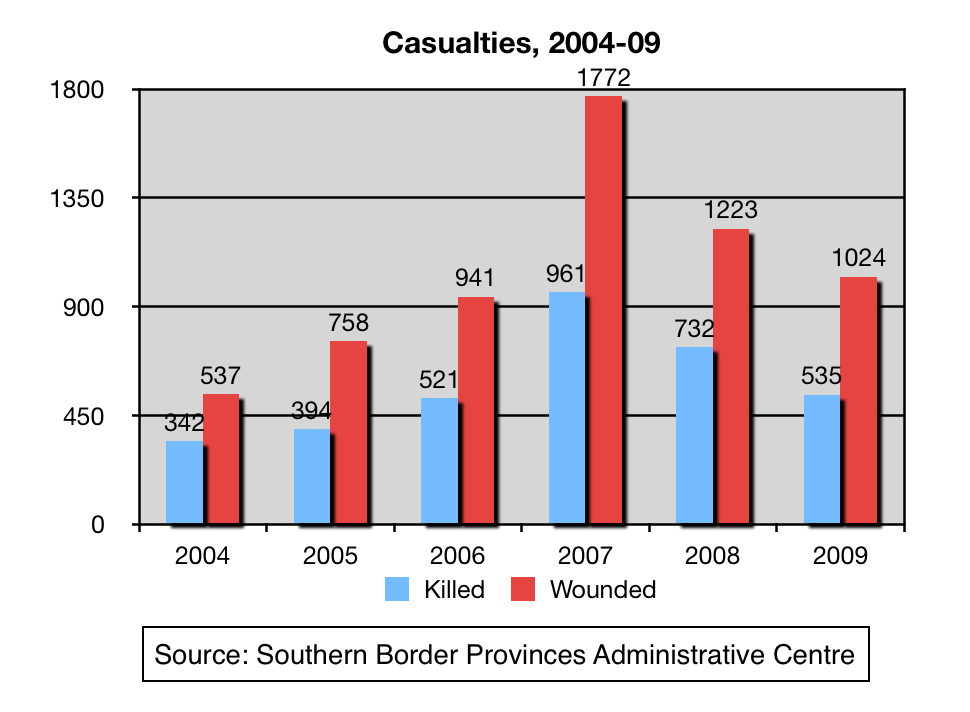

Bombings and targeted assassinations are a way of life in Narathiwat, Yala, Pattani and parts of Songkhla — the areas that comprise Thailand’s Deep South. Nearly 7,000 people have been killed and 12,000 wounded since January 2004.

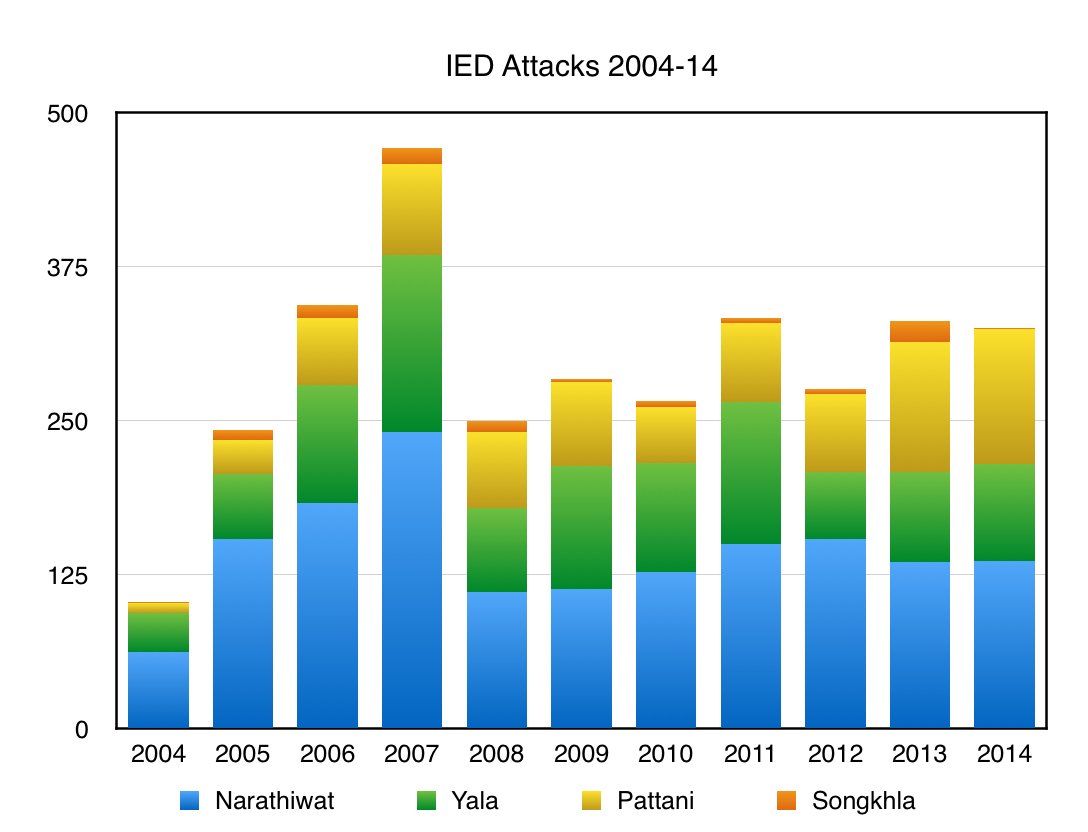

The violence started slowly, and with little widespread support, but some egregious missteps by Thai authorities, including the Krue Se massacre, the Tak Bai incidents, and other botched raids, served as a catalyst for the violence. The level of violence peaked in mid-2007 when well over three people a day were killed. At the time, it felt as if things were spiraling out of control. Insurgents could attack at will.

The Thai military “surged” in mid-2007. And at the same time, it appeared if the insurgents had over played their hand, both logistically and in terms of losing popular support. Violence fell sharply in the latter half of 2007 through 2008. The number of violent incidents picked up again in 2009. And since then, it has plateaued.

The Thai military “surged” in mid-2007. And at the same time, it appeared if the insurgents had over played their hand, both logistically and in terms of losing popular support. Violence fell sharply in the latter half of 2007 through 2008. The number of violent incidents picked up again in 2009. And since then, it has plateaued.

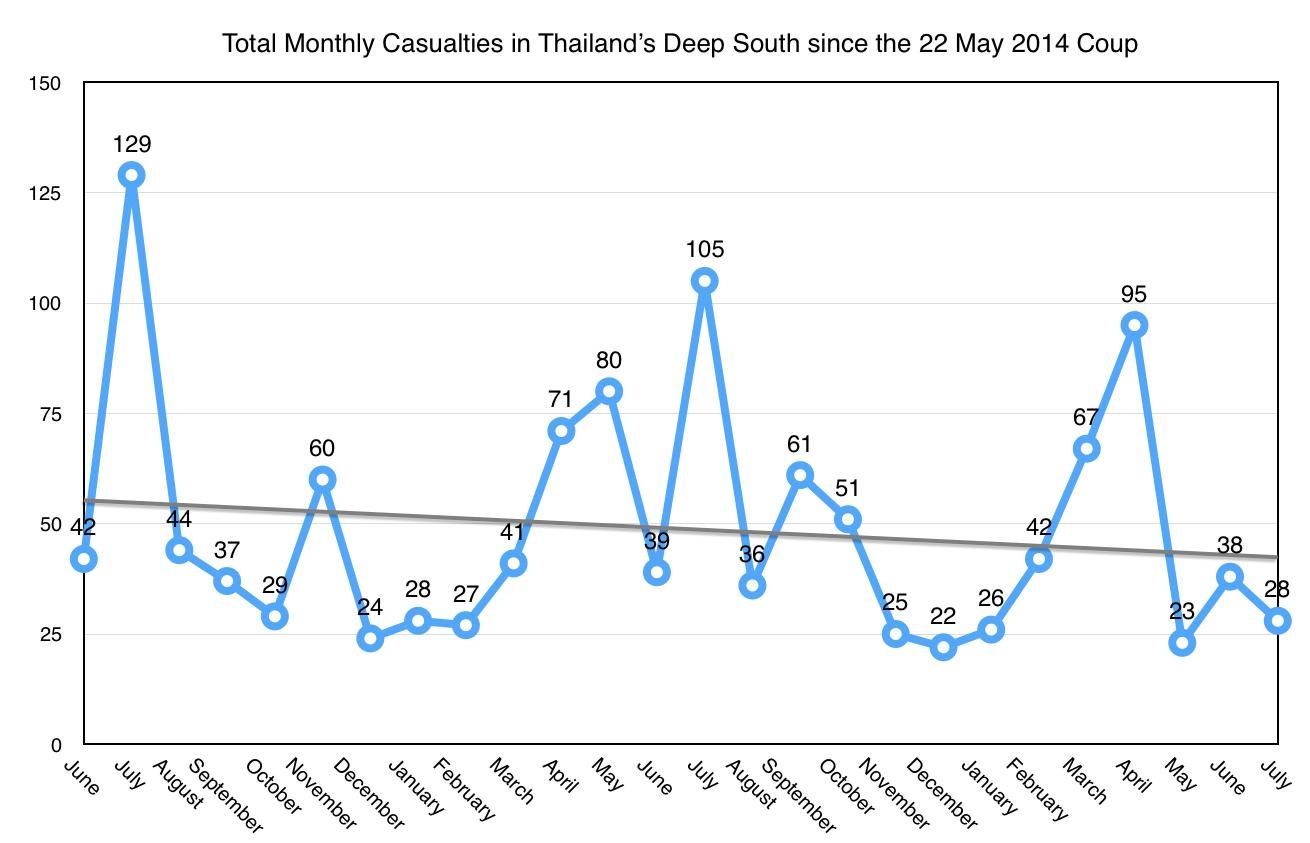

In last week’s piece laying out the case that the Mother’s Day bombings were perpetrated by insurgents, I mentioned that violence had been declining, and for a cadre that was unacceptable. So I would like to lay out some of my data on the insurgency to put what happened last week into greater context. This data is all compiled from open sources.

Many attacks go unreported; many people who are listed as wounded die in the hospital. So this data set is conservative and under-reports the violence. But it does show trends for a conflict that, while generally noted, is little discussed in the media or amongst diplomats because it has been largely confined to the Deep South. With renewed attention on the south, it is worth putting some of this out there.

How many die

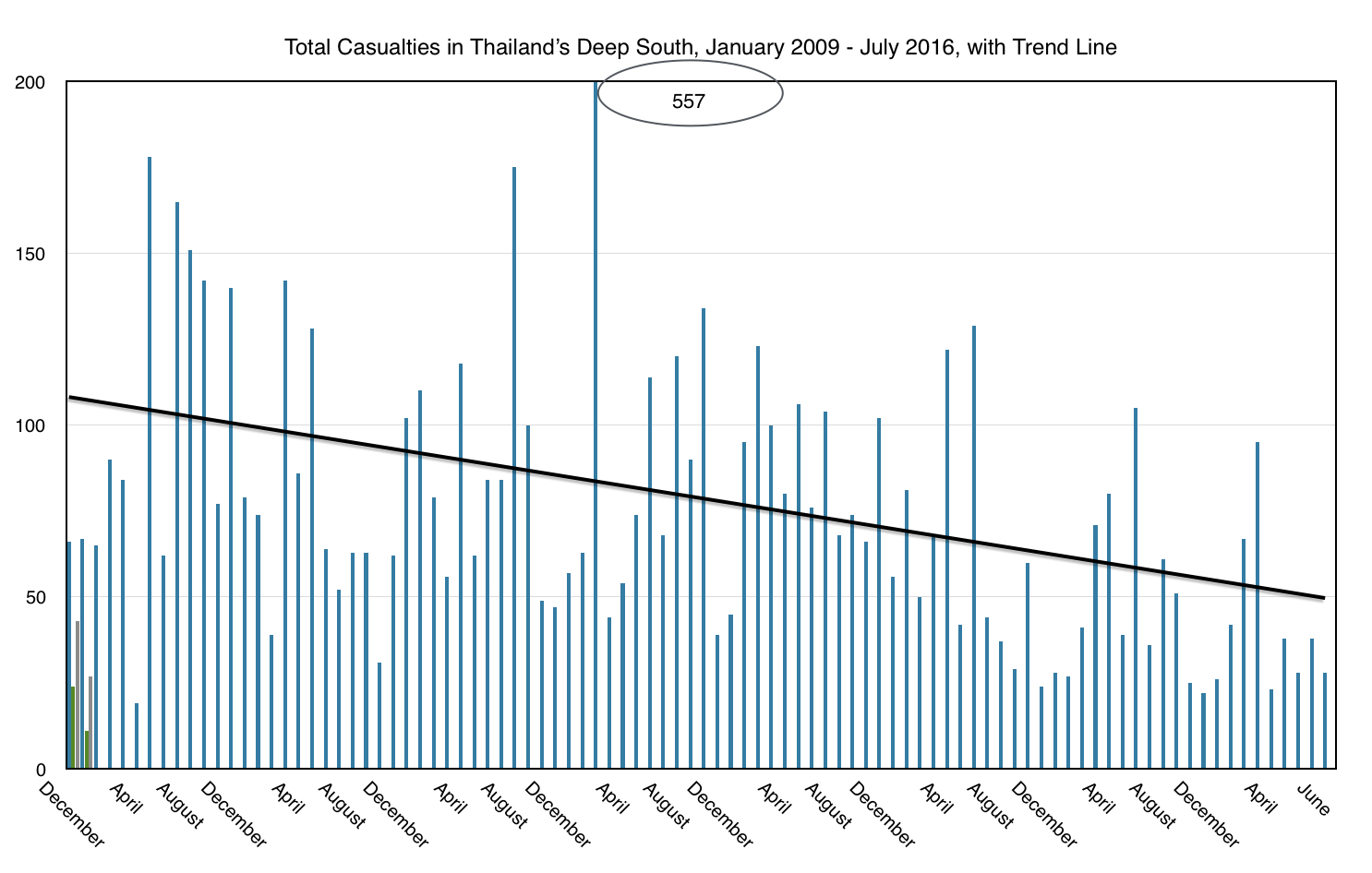

The Thai junta believes that the trend line for violence is in its favour. Since January 2009, the rate of casualties has steadily declined.

Between January 2009 and July 2016, the average monthly death toll was 25. In 2009, the average was 36, in the first seven months of 2016, it is roughly one-third of that. On average 54 people a month have been wounded since January 2009. That number has fallen to 32 in 2016. The average number of casualties since January 2009 is just over 80 a month. After the 22 May 2014 coup d’etat, that number dropped to just over 49 per month; a 38.7 per cent decrease.

The junta likes to take credit for that, but the trend was already clear before their seizure of power. Moreover, that decline has far more to do with decisions on the insurgents, rather than solely government counter-measures. In interviews conducted in October-November 2014 and February 2015, members of the BRN told me that they had calibrated the correct amount of violence to continue to pressure the government without alienating their base of support.

To give the government credit, the network of checkpoints across the south, including cameras to capture drivers, passengers, vehicle and license plates, has made operations in the south more logistically complicated and less safe. But we see that insurgents will ramp it up over a few months, then make a strategic retreat until the government relaxes its posture. There are seasonal fluctuations as well. Insurgencies are living organisms with their own natural cycles and rhythms.

Who dies

Who dies

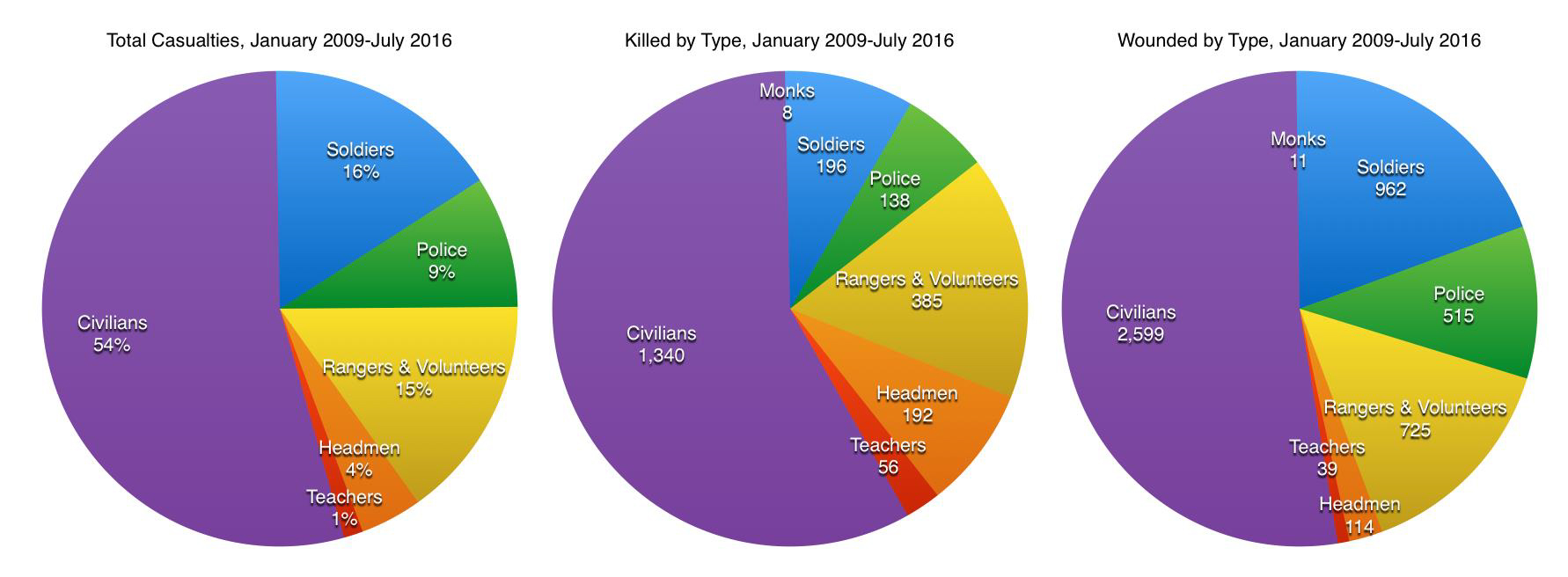

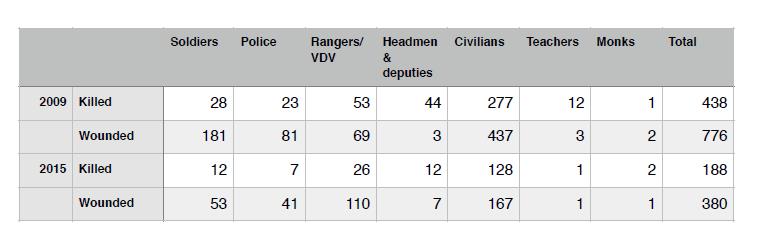

In terms of types of casualties, civilians make up the majority, 54 per cent. Security forces represent 40 percent of the total losses, which is pretty high in comparison with other insurgencies. And those numbers have remained fairly consistent.

Although casualty rates dropped sharply between 2009 and 2016, the casualty ratios remained almost unchanged. In 2009 security forces comprised 24 per cent of the total killed and 43 per cent of all those wounded. In 2016, although the total casualty rate fell by 53 per cent, security forces continued to represent 24 percent of the dead and 53 per cent of the wounded.

The military publicly blames the breakdown in the talks on the 2013 political crisis in Bangkok as the reason that the talks collapsed. But they were dead long before that, due to the violence against security forces and the BRN’s “Five Demands” that were unacceptable to the RTA. But targeting of civilians resumed by Autumn 2013.The insurgents began to lessen their targeting of civilians in mid-2013 with the advent of the peace process with the government. They refused to stop targeting security forces during the peace talks, which is the real reason that the army leadership put pressure on the government to stop holding them.

In terms of security forces, there is a change. Rangers and village defense volunteers now comprise the majority of casualties as the Army continues to draw down its troops and implement the “Thung Yang Dang model.”

The majority of civilians, as well as headmen, are fellow Muslims. Increasingly the rangers are being recruited from the local community, and the majority of village defense volunteers are also Malay.

Insurgents have targeted teachers and monks, but not frequently. Since 2004, 179 teachers were killed, including 56 since January 2009. The 180th teacher to be killed died this month when an IED targeted him and two police officers on teacher protection detail. Though only 19 monks have been killed or wounded since 2009, like teachers, their targeting has a disproportionate impact on the Buddhist community in the south, and thus the government’s response.

How they die

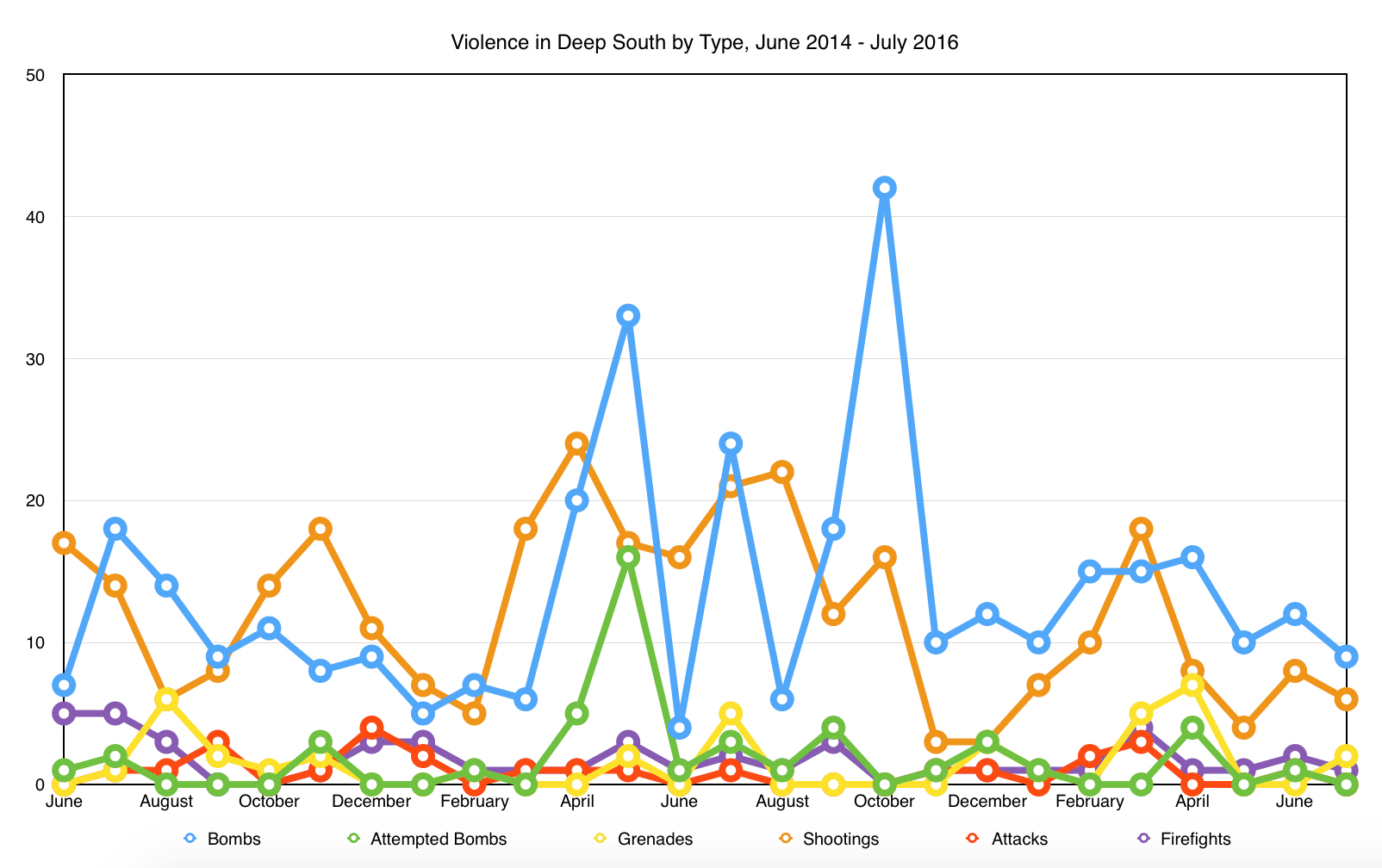

There are very discernible trends in the violence. A month may have high levels of IED attacks, dropping sharply in the following month.

The simple answer for this pattern is that the insurgents use up their materiel, and it just takes them time to restock. The logistics of running an insurgency on the cheap and without sponsorship are real.

The other reason is that insurgents are very responsive to how the government deploys its personnel. For example, after a spate of arson attacks on schools, the government tends to increase the deployment of security forces to protect them, so the insurgents move on to other targets.

The first 10 days of August are pretty indicative. There were some 39 incidents of violence, including 35 IEDs. In the first three days of the month, there were five largish IEDs, that wounded two women, two village defense volunteers guarding a school, two Border Patrol Policemen traveling in an APC, and a village chief and his five-man security detail.

Many of the IEDs were quite small and not intended to kill; 19 were used to knock down power polls, not target individuals. In addition, they set fire to a large wood processing factory in Yala’s Bannang Sata district causing 50 million baht in damages. But remarkably, the largest attack never occurred: police defused a 90kg car bomb in Yala’s Raman district.

What is consistent in the chart above, is that insurgents are very conservative; they engage in attacks on hardened security force outposts and sustained firefights with security forces infrequently.

Since 2009, there has been, on average, one attack on hardened outposts a month. That figure has not changed since 2009. Simply it is too risky for the insurgents. They engage in more firefights with security forces per month, usually in an ambush following an IED attack. In 2009, they fought in roughly four a month; in 2016, the average is three per month.

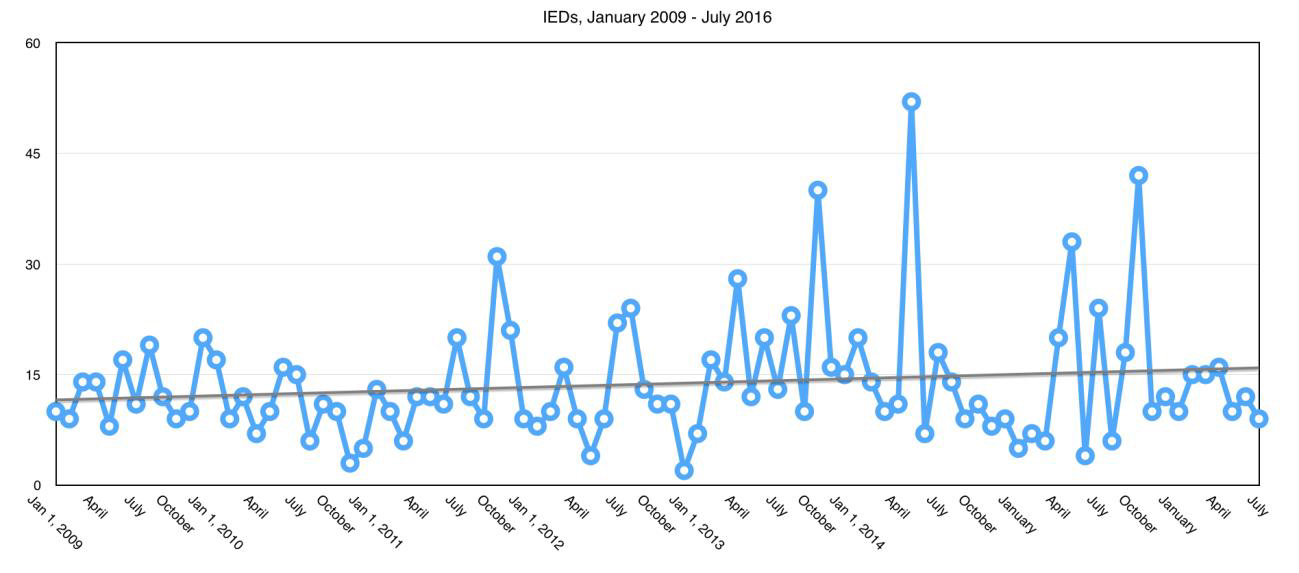

Since January 2009, there have been 1,260 IEDs. In addition, there were at least 169 IEDs that security forces defused or that failed to go off. What’s interesting is that the trend line for IEDs is going up, even if the overall casualty rate is going down. Right now, we are well below the average since 2009.

Today, IEDs are mostly deployed in the countryside, along rural roads targeting security forces. The number of IEDs used in cities against the civilian population has dropped markedly. Civilians are killed and wounded in IED attacks, but mainly as collateral damage.

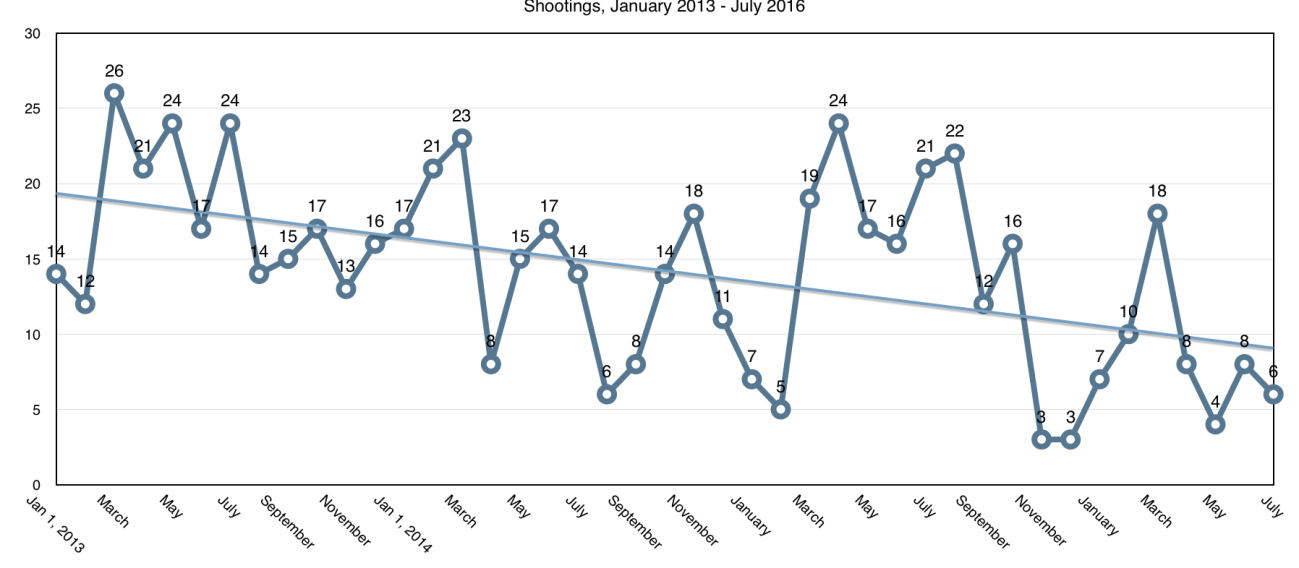

Many of the civilian casualties come from shootings; the most common are by a pillion rider on a motorcycle. Insurgents target people they deem to be collaborators, Buddhists, and government officials, including village headmen and their deputies.

Many of the killings are tit for tat, in retaliation for a government action, such as a raid, arrest or extrajudicial killing. For example on 5 July 2016, a woman was gunned down in Sungai Golok. Insurgents left a note on the body saying that it was in retaliation for grenades lobbed into a mosque days earlier.

The shootings are very easy to perpetrate and in some ways, it is surprising that there are not more of them. Again, the insurgents are not into this for the sake of violence; they try to calibrate the level of violence and make sure people understand that there is a reason for the people that they target.

There have been over 40 beheadings since 2004, though only 12 since 2009. What is more commonplace is desecration — usually burning — of corpses. It is simply gratuitous violence meant to shock and terrorise the local population. When I asked insurgents about beheadings and desecrations, they actually thought that it was a very effective tactic, but had limited its use as the local population found it to be beyond the pale.

There have been over 500 major arson attacks (not including the regular torching of CCTVs) since 2009, including 35 schools. In addition, insurgents routinely detonate bombs on the train tracks, as they did on 3 July 2016, when two bombs shut down train services south of Yala for roughly a week.

Where they die

IED attacks over time have become more spread out across the south. There is a similar geographical distribution for casualty rates.

And yet…

And yet this drum beat of violence has not been enough to compel the government to engage the BRN in a meaningful dialogue as my colleague Rungrawee Chalermsripinyorat noted. The violence has been mostly contained to the Deep South, far from the concerns of the junta or its core supporters. The new constitution precludes any hope of political devolution, let alone autonomy.

The RTA has routinely rejected a general amnesty and has worked hard to degrade the capabilities of the insurgents, or at least make attacks in the south much harder to pull off. (Ironically, it might be easier and safer for insurgents to perpetrate attacks outside of the Deep South). They are trying to get the violence to a low enough level that they can ascribe it to crime.

I think it’s clear that we are seeing some of the BRN’s Young Turks who are very frustrated at where the movement is right now, who clearly believe that they need to ratchet up the violence, in order to get Bangkok’s attention.

They need to raise the costs for the junta’s hostile position and intransigence.

Zachary Abuza is a professor at the National War College where he focuses on Southeast Asian politics and security.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss