Tensions in troubled waters see more and more attacks and the undermining of precarious livelihoods.

In early March, 59-year-old Trần Sinh and his crew were retrieving fishing nets when a Chinese coast guard boat steamed rapidly toward his boat.

When very near to his wooden craft, Sinh later told a journalist, men in the much larger steel-hulled vessel shouted something in Chinese, which he didn’t understand. Then, in stilted Vietnamese, a Chinese sailor screamed: “these waters belong to China; you and all Vietnamese boats must leave immediately.”

As Sinh and his crew accelerated their efforts to bring in their nets, Chinese sailors opened fired, riddling his vessel with bullets and injuring one of his men. Sinh then throttled his boat’s engine to leave as speedily as possible. Hours later, he and his crew reached port in his badly damaged boat.

Sinh, like thousands of other Vietnamese fishermen, is fighting for his livelihood against China, which claims waters that he and his village have fished for generations. This tragic fight is not well known beyond Vietnam.

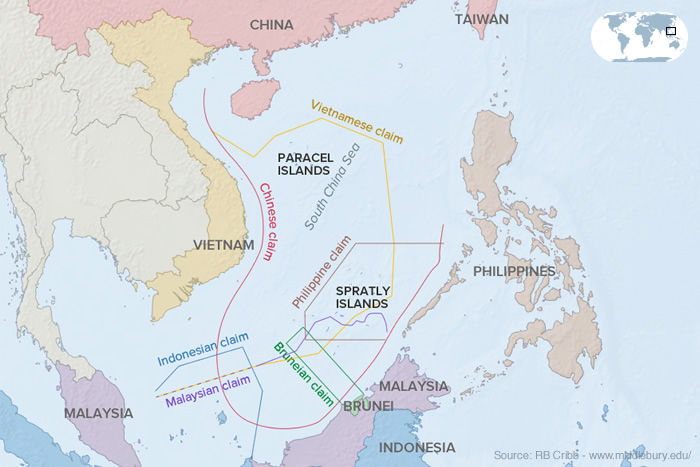

Sinh’s boat was within Vietnam’s 200 nautical mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), the distance allowed by the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. According to over 200 Vietnamese newspaper articles and other reports I have read about the fishermen’s plight, virtually all Vietnamese fishing boats attacked by Chinese since 2001 were within this zone; often they were less than 50 nautical miles from Vietnam’s shoreline. China’s government, however, claims exclusive rights to the whole area, about 80 per cent of the South China Sea. Ignoring the EEZs of Vietnam and other Southeast Asian nations, Beijing officials insist China’s claim is indisputable.

“It is totally absurd,” exclaimed fisherman Tiêu Việt Là, “to say that we Vietnamese are violating Chinese territorial waters. We are fishing in waters belonging to Vietnam, captured and occupied by Chinese!” He said this to a reporter in July 2010, a few months after Chinese had abducted him and his boat for the fourth time since 2007, each instance costing him dearly before being released.

“Even though Chinese boats pounce on us, causing much hardship,” fisherman Phạm Văn Dũng of Phu Yến province told another journalist in May 2011, “I won’t abandon those fishing areas. The waters [near Paracel Islands] belong to my country, and I must make a living.”

Mại Phụng Lưu, a fisherman in Quảng Ngãi province, recounted that Chinese had seized him and his boat and crew “in Vietnam’s waters, waters where my grandfather fished, my father fished, and now I fish. Those waters are our history and our territory.”

As Vietnamese fishermen struggle to protect their livelihoods, their fishing grounds, and their country’s territory, Chinese steal their equipment, damage or sink their boats, abduct them, extort money, and beat them. Chinese have even killed several Vietnamese fishermen. In January 2005, Chinese vessels rained bullets on two fishing boats less than 20 nautical miles from Vietnam’s coastline, killing nine and gravely wounding seven Vietnamese. The attackers then held the survivors and the two boats until the fishermen’s families paid substantial sums of money

According to Vietnamese government figures, 7,045 fishermen on 1,186 boats were attacked by foreigners, mostly Chinese, between 2006 and March 2010. Comparable figures for years since are unavailable but are likely larger. Since 2010, China’s government has intensified efforts to enforce its claims. Between November 2015 and early April 2016, for instance, Chinese assaulted one-third of the fishing boats from just one village in Thừa Thiên Huế province. During 2015, Chinese attacked 20 per cent of the fishing boats in Lý Sơn, a community in Quảng Ngãi province.

Often the attackers are in Chinese coast guard and military vessels. Some attackers are in unmarked boats, which Vietnamese fishermen say are usually Chinese. In late November 2015, for instance, two unmarked boats with eight armed men, came close to a Vietnamese fishing boat near the Spratly Islands and started shooting, killing on the spot 42-year-old fisherman Trương Đình Bảy. The two vessels and the method of attack used, said the surviving fishermen, were like others employed by Chinese against Vietnamese.

Until about 2011, Chinese frequently abducted Vietnamese boats and crew, taking anything of value and beating and starving the fishermen until their relatives paid money far beyond their means, forcing families to sell their homes and resort to other drastic measures. More common recently, armed Chinese board fishermen’s boats; rob crew members; strip or destroy the boat’s navigational instruments and other equipment; take or dump its catch; and confiscate much of its petrol and fresh water, leaving only enough for the crew and boats to limp back to port. Sometimes Chinese vessels ram, even sink, Vietnamese fishing boats leaving the fishermen floundering in the ocean.

Fishermen want the Vietnamese coast guard and navy to protect them against the Chinese, but officials say they lack sufficient ships and other resources. Government offices frequently assist fishermen after Chinese have attacked and released them. And Vietnamese authorities regularly object to their Chinese counterparts and reiterate that the fishermen are using waters belonging to Vietnam, not China.

Chinese authorities, however, continue to disagree and to attack Vietnamese fishing boats and crews.

Benedict J Tria Kerkvliet is Emeritus Professor at the Australian National University and Graduate Faculty Member at the University of Hawai’i.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss