There is a history of Singapore that is taken as a straightforward truth by millions of people in the world. According to this narrative, up until 2004 the city-state was an unliveable hellscape where violent crime, drug trafficking, terrorism, murder, and corruption ran rampant. Women were practically raped on sight, the streets were strewn with garbage, and traffic was insolubly chaotic.

All of this changed that year, when the new prime minister, Lee Hsien Loong, instituted the death penalty for all violent criminals, drug traffickers, and corrupt officials. As a result, the prison population was reduced from 500,000 to 50 within six months (presumably through mass executions). Moreover, in what appears to have been a matter of weeks, crime vanished, Singapore became an economic powerhouse, its universities shot up in the world rankings, and its citizens became trilingual. The draconian use of capital punishment, according to this narrative, is the secret to having a peaceful, developed country.

This narrative was popularised on the Spanish-speaking internet through a post authored by a Cuban pastor based in Honduras named Mario Fumero. Fumero’s blog, United Against Apostasy, published a series of articles extolling Singapore’s purported crime-reducing policies. Fumero suggests that all Latin American countries should emulate Singapore’s example and exterminate all offenders (either through judicial or extrajudicial means), so that Latin Americans will promptly reach the desired development that Singapore now enjoys.

To get a sense of how widespread this narrative is, Fumero himself comments that these articles on Singapore are by far the most popular posts on his blog, a blog which has attracted over 20 million views. The actual reach of this particular article, however, goes much further. Its text has been copied or paraphrased in various YouTube videos that, taken together, add up to hundreds of thousands of views. It has been reproduced on several posts on Taringa! (an extremely popular Spanish-language “community knowledge” website), and reposted on countless blogs and forums. Its contents have even been copied in printed newspapers (with evidently poor fact-checking standards), and they have been cited as the basis of numerous editorials published throughout Latin America.

The number of Spanish speakers who have been exposed to this narrative through social media can probably be estimated in the millions; for many of them, this portrait of Singapore is axiomatic by virtue of its ubiquity. Few people have sufficient familiarity with Singaporean history to challenge this narrative.

Fumero has a concrete political agenda: the reinstatement and dissemination of the death penalty in Latin America. Although he has stated that he is against capital punishment, he immediately qualifies such statements by arguing that “…there are situations in which it [the death penalty] can be justified even biblically, becoming the only option for instilling fear in a system where impunity prevails, and where there is a lack of respect for life.” In fact, a quick glance at the many columns written on the basis of his article—as well as the comment sections of any of the websites where his article has been reproduced—reveals that the “successful” Singaporean case has become a key touchstone for the pro-death penalty agenda in Spanish-speaking virtual forums. Along with them, Fumero insists on the exemplary success of the alleged Singaporean policy of indiscriminate judicial executions.

For Fumero and his supporters, it is precisely Singapore’s prosperity and rigidity that they find useful in their attempt to promote a particular political agenda. Latin Americans may not know much about Singapore, but they have heard that it is a rich and seemingly excessively disciplinarian country—the ban on chewing gum is well-known. Along with almost complete ignorance of the country’s history, due to hitherto relatively limited cultural and academic exchange, the conditions are perfect for historical visions like that one conjured by Fumero to flourish. With a contemporary Orientalist twist, he fabricates history to create a simulacrum of an “exotic” country to advance his disciplinarian agenda. The fable he creates serves to answer questions such as “why are they prosperous and we are not?”, or “why is there so much crime here and not there?”. These questions correspond to Orientalising impulses which presume that, unlike North America or Europe, Singaporean prosperity is not natural, and there must therefore be some kind of secret to success that Latin Americans could appropriate as a shortcut to “development.”

But why should we care about this? After all, a generation of young Spanish-speakers with a completely distorted view of a remote country like Singapore could be dismissed as a mere anecdote, as a sort of contemporary version of the Prester John myth. However, Fumero’s article is not just a harmless fable; it is the historical narrative that frames a call to action, action which would ultimately promote the judicial or extrajudicial execution of thousands of people. The sobering reality of Rodrigo Duterte’s popularly-endorsed campaign of extrajudicial execution of alleged drug pushers is too blatant, too painful, for us to ignore historical narratives which might justify such policies. Law and order narratives have been successfully deployed time and time again to win elections in Latin America, claiming to end crime and drug trafficking in blood and fire, but without producing significant results.

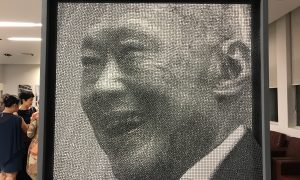

Like Fumero, the Singaporean state and many Singaporeans have their preferred historical narrative as well, albeit one that is demonstrably less fanciful. It runs something like this: the People’s Action Party (PAP), headed by Lee Kuan Yew, steered Singapore through the chaos of separation from the Federation of Malaya in 1965. Since then, it has, through technocratic competence and indomitable strength of will, propelled Singapore towards a multi-ethnic meritocracy, good governance and a dynamic capitalist economy. If authoritarian-leaning practices were developed along the way, they are dismissed as the price of success in the face of adversity. This narrative is integrated into the national curriculum, espoused by politicians, and provides the thematic framework for performances staged by students and volunteers at the annual national day parade. It pervades journalistic discourse in both Singaporean and international media organisations. Naturally, this treasured mythos of nation-building elides many unsavoury things, but there is more than a kernel of truth to it.

Singapore’s national mythos is primarily meant for domestic consumption, but it is also part of how Singapore projects itself to the rest of the world. Its preferred origin story of chaos to order, of insecurity to wealth, is an integral part of Singapore’s carefully-cultivated image as a good place to do business, park one’s money, and educate one’s children, or even to hold international summits. This narrative is deployed for specifically political purposes: the trope of dependable PAP stewardship leading to economic success is routinely deployed at campaign rallies before each general election.

By contrast, Fumero’s reformulated narrative of Singaporean history deliberately misrepresents the underlying reasons for Singapore’s perceived success to an audience familiar only with a fleeting image of Singaporean “success”. This (ab)use of Singaporean history is instructive, because it sheds light on how powerful a tool history can be in the “post-truth” era—even when it is deployed far from its point of origin and targeted at a very different audience.

Fumero’s article represents an unusual permutation of the weaponisation of history: we are used to the idea that history is weaponised, usually by states (authoritarian or otherwise), for domestic political purposes. We are less used to the notion of history being mined far from its point of origin to generate political gain in seemingly irrelevant contexts, especially by non-state actors like Fumero.

That, however, is exactly the opportunity that the post-truth era of social media-driven news affords, and various actors have not been slow to seize it. The destabilisation of informational legitimacy—which until recently for most people was embodied in whichever newspapers and televised news channels were most readily at hand—is not the heart of the problem. The number of gatekeepers, and the location of the gates themselves, have changed. With the low barriers to entry afforded by internet access, both state actors with modest budgets and non-state actors with virtually no budget at all can now shape historical narratives, with serious consequences for the societies in question.

Fumero’s article may be an outlandish example, but it forces us to confront the reality of how history can be successfully weaponised; the consequences of his historical fabrications are hard to measure and may have yet to flower. How much easier would it be for an organisation with more resources to weaponise history, and what havoc could it wreak? The state’s existing tendency to weaponise history already gives citizens sufficient cause to equip themselves mentally to resist these historical narratives, and the cultivation of citizenries capable of evaluating or filtering information (though inconvenient to the state) has become more important than ever for democracies.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss