PoP first came across Jeffrey Mellefont, an Honorary Research Associate at the Australian National Maritime Museum (ANMM), when we read one of his lyrical articles in Signals about viewing a total solar eclipse while sailing in the Moluccas (“All I can say is, how extraordinary to live in a solar system where our one and only moon fits perfectly over the sun”). We are now delighted to feature Jeffrey as a guest blogger, in a special post about UNESCO’s recent heritage-listing of Indonesia’s wooden boat building traditions.

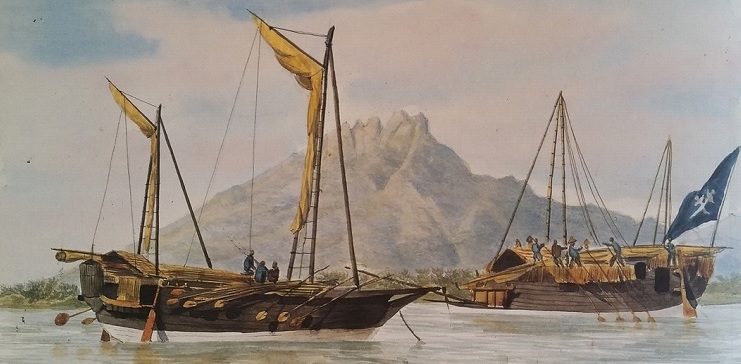

LEFT: Pinisi trading ship on the Barito River, S.E.Kalimantan, 1983.

RIGHT: Patorani fishing boat, Makassar Harbour 1985. Photographs: Jeffrey Mellefont

Across the 17,000 equatorial islands comprising the Republic of Indonesia, the ingenious arts of timber boat building have been a crucial enabler of human ventures from prehistoric times until today. As ports, kingdoms and states developed, distinctive traditions of boat building and seafaring underpinned trade, politics and warfare, transport and communications as well as day-to-day livelihoods and subsistence … more so in this sprawling tropical archipelago than in just about any other region in the world.

These accomplished seafarers, key participants in the world’s spice trade since ancient times, have also had long-standing economic and cultural connections with nearby northern Australia and its Indigenous coastal populations. Best-known was a centuries-old fishery that brought annual fleets from the central Indonesian island of Sulawesi, harvesting a costly, luxury marine product for trade with imperial China. This teripang or bêche-de-mer industry was long-established when British settlers first arrived, but was prohibited in 1906 by customs officials of the new Commonwealth of Australia.

In December 2017, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) formally recognised the cultural significance of the boat-building that had enabled such long-distance voyaging (to Australia and many other places as well).

The 12th Session of the UNESCO Unique Cultural Heritage Committee voted to include the ‘art of boatbuilding in South Sulawesi’, part of a ‘millennia-long tradition of … boat building and navigation’, among the world’s Intangible Cultural Heritage. This was added to existing UNESCO listings of unique Indonesian cultural expressions such as wayang kulit shadow-puppet theatre, the wavy-bladed kris dagger that’s hand-forged of meteoritic nickel-iron, and batik, a spectacular wax-resist dyed textile.

This ‘art of boat building’ nomination recognises a specific type of South Sulawesi vessel, the pinisi, as the embodiment of this tradition.

Last of the engineless pinisi setting sail for Java with a cargo of sawn timber, Banjarmasin, South-East Kalimantan 1983. Photograph: Jeffrey Mellefont

Pinisi were the engineless trading ships built and sailed in the 20th century by the seafaring cultures of South Sulawesi, most notably the Bugis and the Makassan people. They featured a tall, powerful, topsail-ketch rig with unusual, permanently standing gaff booms. (A ketch is a fore-and-aft rigged vessel with two masts, where the larger or main mast is always forward of the smaller or mizzen mast.)

Today the term pinisi is often applied to the very large, motorised timber ships that replaced them, hand-built in the South Sulawesi style by Bugis or Makassan shipwrights and trading all over Indonesia. Some still carry small auxiliary sails. In ports where these contemporary ‘pinisi’ traders gather in large numbers, such as Jakarta’s Sunda Kelapa, they’re a tourist attraction.

Motorised traders that developed from the 20th century sail-powered pinisi haul mixed cargos, servicing remoter island ports. Location: Bima harbour, Sumbawa 2011. Photograph: Jeffrey Mellefont.

The same shipwrights also produce timber ‘pinisi’ to order for tourist companies, who install comfortable fitouts and accommodations for diving or cruising holidays. They’re often fitted with auxiliary sails based on the historical 20th-century pinisi topsail-ketch rig.

The sailing pinisi has become a proud national icon for modern Indonesia representing its immemorial maritime traditions, appropriated by governments, organisations and businesses for branding and imagery.

Pinisi as a national icon: 100 Rupiah bank note; football club trademark; 1:5 scale model at Makassar international airport; sea salt packaging. Photographs: Jeffrey Mellefont.

Formerly, in Bugis and Makassan boat-building traditions, the term pinisi referred to this particular seven-sail, gaff-ketch rig in the same way that English terms like ‘ketch’, ‘schooner’ or ‘brig’ refer to specific configurations of masts and sails. The pinisi is often misnamed in tourist brochures or popular literature as a ‘schooner’ – a romantic Western term that most people recognise without realising that it refers to a type of rig that differs from a ketch or a pinisi.

In ship’s registration papers and elsewhere, the term pinisi has been variously spelled phinisi, phinis, pinis and penis. It’s been suggested that the term derives from the European word ‘pinnace’, a small sailing craft. What’s certain, however, is that the pinisi’s standing-gaff ketch rig is a design adapted by its builders from colonial-era Dutch or other Western vessels observed in these waters.

How can we reconcile this with the pinisi’s acceptance by UNESCO as Indonesian cultural heritage?

In this respect it’s important to recognise that Indonesian boat building, like many other aspects of its cultures, is both dynamic and adaptive. Its traditions have been anything but static, adopting external influences and transforming them into unique new forms that retain older features as essential elements. This propensity, sometimes called ‘syncretism’, has been widely recognised in Indonesian religions and arts.

Thus we can consider the vessels called pinisi to be a recent, syncretic expression: a development of boat-building processes and technologies that were a distinctive part of this island world, where ancient trade routes and many overseas influences have converged.

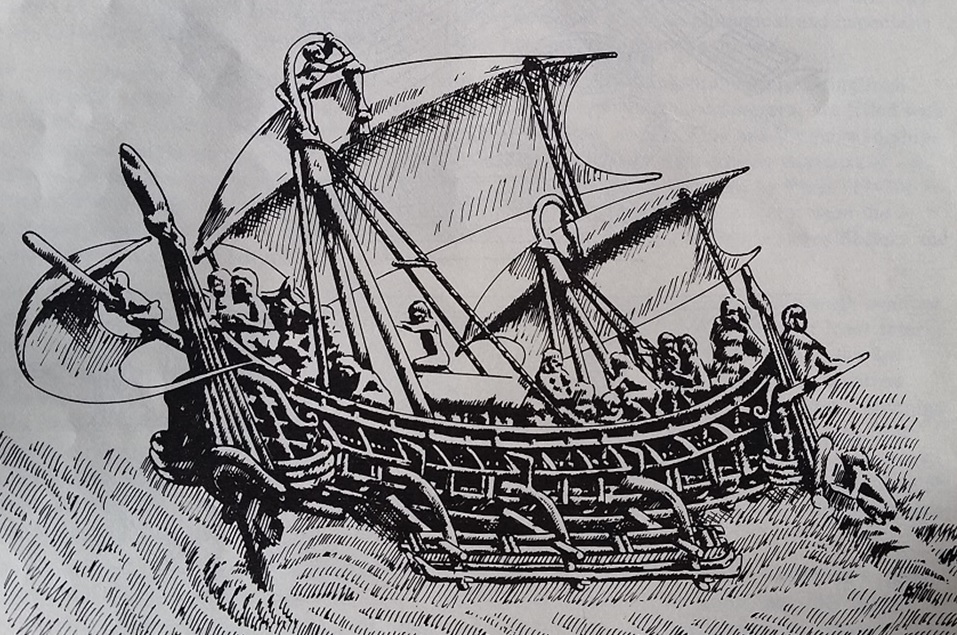

Medieval Javanese ship with tripod masts, canted rectangular sails, quarter-hung rudders, depicted in 8th-century temple frieze at Candi Borobudur, Central Java. Drawing by Chris Snoek, from The Prahu by Adrian Horridge, OUP, 1981

Certainly, hull construction and designs of sails, rigging and steering gear in these islands were very different from those of the equally diverse Chinese, Arab and European ships that traded into the region over millennia – the late-coming Europeans arriving from the early 16th century. These distinctive design features are clearly recorded as far back as the 8th century AD, on detailed Javanese stone friezes. Some can still be found in use today.

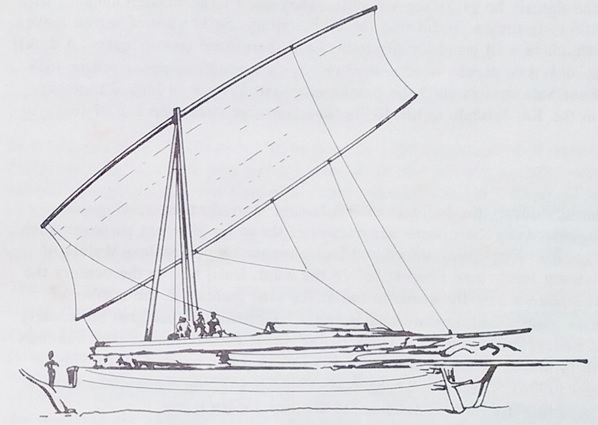

Some of these unique features were noted by European mariners who encountered the annual fishing fleets from Sulawesi while exploring the northern coasts of Australia in the 19th century. A drawing by explorer Matthew Flinders’ expedition artist William Westall, made in 1803 while circumnavigating Australia in HMS Investigator, shows some distinctive elements of earlier Bugis or Makassan ships from which the pinisi developed.

Double-ended Bugis-Makassan pajala-style ship with tripod masts and canted rectangular sails (some of them lowered and stowed on deck), as well as quarter-hung rudders. William Westall, Arnhem Land (Northern Australia) 1803

Most notable is the large, canted rectangular sail stretched between two booms of flexible bamboo, well-controlled by sheets, vangs, guys and braces. It hangs from a tripod mast that requires no stays to keep it up. This rig, called tanja, is a distinguishing and demonstrably ancient feature of these seafaring cultures. The sail, of woven palm-leaf, was furled by rolling it around the lower boom. This is a fore-and-aft rig, capable of sailing into the wind (to some degree). Like a sail board, the vessel can be steered by varying the tilt of the sail.

Steering is further aided by twin rudders that hang outboard over each stern quarter, lashed to beams protruding from the hull. These ocean-going vessels carried palm-thatch deckhouse structures and hold coverings, and usually lacked fixed or sealed deck planking. The same hull form that Westall recorded can still be found in fishing boats hand-built on beaches in South Sulawesi today. This double-ended hull (that is, having a similarly shaped bow and stern) is a signature of Bugis-Makassan marine architecture.

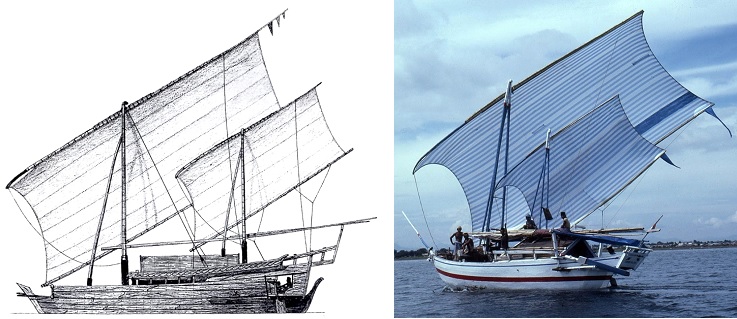

Model of a 19th-century Bugis-Makassan padewakang by Nick Burningham, Northern Territory Museum. Note main and mizzen masts and sails, overhanging stern deck. ANMM Collection

Later 19th-century illustrations and ship models show developments of this design. Large voyaging ships from this culture, called padewakang, were now built with multiple masts and overhanging, squared-off stern structures, influenced possibly by those ships visiting from Europe, China or the Indian Ocean. A replica padewakang was built in Sulawesi and sailed to Darwin in 1988. It is preserved in the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory to illustrate the historical Bugis-Makassan voyages.

Nineteenth-century records also show Indonesian builders experimenting with European-style sails, combining bowsprits, jibs and gaff ‘spankers’ (mizzen sails) with their own traditional rectangular tanja sails. An 1830s watercolour by French explorer François-Edmond Pâris shows an early attempt by Indonesian shipwrights to adapt the European standing-gaff sail to their customary tripod masts.

TOP: Javanese ‘jonque’ with added Western bowsprit, jibs and spanker, watercolour by Thomas Baines 1856. Collection National Library of Australia. ABOVE: Early record of standing-gaff ‘ketch’ rig on a Sulawesi ship, 1831. Cargo vessels of Makassar, at Besuki [Java], watercolour by François-Edmond Pâris. Collection Musée de la Marine, Paris

With three jibs flying from a novel, triangular bowsprit, and separate topsails for lighter winds, the ketch-rigged palari-pinisi offered easier handling of its smaller individual sails and more flexible sail combinations for different wind strengths. This became a vital advantage as engineless pinisi grew from 20 to 300 tonnes to meet a pressing need for shipping in the early decades of independence after World War II. The versatile rig came to dominate long-distance trade routes across the archipelago, until motorisation of this fleet was completed in the 1980s.

Palari-pinisi trader at Makassar, South Sulawesi 1932, photograph by Geoffrey Ingleton RAN. ANMM Collection

These hybrid craft continued to use distinctly Bugis and Makassan construction techniques, and traditional design features such as tripod or bipod masts and twin quarter rudders. And as long as pinisi were built, the same shipwrights continued to produce smaller fishing craft with unmodified hull forms and tanja sails.

Continuity of boat-building traditions. LEFT: Study for replica of a 19th-century padewakang, Nick Burningham 1987 Northern Territory Museum. RIGHT: Patorani , a Makassan offshore fishing vessel 1985. Jeffrey Mellefont photograph

Certain unique construction techniques are central to UNESCO’s endorsement as intangible cultural heritage. Never built to plans, Bugis-Makassan vessels were made with ritual, prayer and ceremony, following a series of proportions memorised by master builders and passed down the generations. In the original traditions, individual timber components including planks were not sawn but hand-sculpted by adze and chisel, each piece uniquely shaped and named, and fastened by tight-fitting wooden pegs or bindings of rattan. No iron fastenings were used at all.

Very few traditions are completely hermetic and these builders have embraced electric drills, chainsaws and sawn planks to speed up production. Massive trading vessels of up to 500 tonnes are still hand-built on beaches by the heirs of these ancient traditions.

Knowledge of the older techniques remains. In a recent project, Makassan master shipwrights built an old-style padewakang at Tana Beru, South Sulawesi, dismantled and air-freighted it to Europe and reassembled it for an exhibition about Indonesian trading empires and their arts.

UNESCO recognition will encourage the survival of this knowledge and skills. What’s important to remember, though, is that while it names and honours the boat building arts of South Sulawesi pinisi builders, this is but one of many, very diverse boat building traditions that have evolved in the Indonesian archipelago among its many and diverse suku bahari or maritime cultures. Among them are the Madurese of the Java Sea, the widely dispersed Sama Bajau (the Sea Gypsies) and the sea hunters of Lamalera in Nusa Tenggara.

Tourist cruise ships operated by Indonesian company SeaTrek, helping to preserve pinisi heritage and sail-handling skills. See the author’s ANMM blogs set on Ombak Putih (left) and Katharina (right). SeaTrek photograph

Jeffrey Mellefont, ANMM Honorary Research Associate

This blog was first published by the Australian National Maritime Museum.

Follow the PoP conversation on Facebook and Twitter!

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss