Findings from a nationwide survey commissioned by Yangon-based NGOs Colors Rainbow and &PROUD indicate that Myanmar’s general public are in favour of greater equality for the country’s LGBT* population, and that a strong majority of people do not support the current criminalization of LGBT people.

With an election around the corner (featuring the country’s first openly gay candidate), activists in Myanmar will soon be presented with a renewed set of policymakers with whom reform can be pursued. The strategic use of this new public opinion data can play a critical role in convincing the Myanmar government to dismantle laws that justify discrimination and marginalization of the country’s rainbow folk – but there are hurdles ahead.

The push for LGBT equality in Myanmar takes place within a broader context of increased attention on sexual and gender minorities across the Asia Pacific region. Positive examples include India’s dismantling of anti-sodomy laws in 2018 and Taiwan’s recognition of same-sex marriage in 2019. Elsewhere, however, there are some more worrying cases, such as Brunei’s near-instalment of the death penalty for homosexuality, public officials spouting anti-LGBT vitriol in Indonesia and Singapore’s high court quashing an attempt to decriminalise male same-sex relations.

The criminalisation of LGBT people in Indonesia

How sensationalism is driving the campaign against LGBT rights.

In Myanmar, ‘LGBT’ is the term used to describe sexual and gender minorities, rather than the longer and more inclusive form of the acronym – LGBTIQ – that is more common in Western rhetoric and advocacy. Accordingly, to align with the Myanmar context, this study and subsequent analysis uses the term ‘LGBT’. In any case, both acronyms are rooted in Western conceptualisations of sex, sexuality and gender that do not always perfectly translate into Myanmar’s cultural or linguistic realities.

In Myanmar, people of diverse sexualities and gender identities face human rights abuses and violence on multiple fronts for not conforming to culturally-entrenched understandings of gender norms and behaviours. LGBT individuals frequently suffer physical, sexual and emotional abuse at the hands of family and household members, and others in their communities such as law enforcement officers, neighbours, teachers and classmates.

Such cases are rarely taken seriously by Myanmar’s authorities. This reality was made clear following the highly publicised suicide of 26-year-old gay librarian, Kyaw Zin Win, who took his life in June 2019 after being forcibly outed and bullied by his colleagues. The Myanmar National Human Rights Council dismissed any wrongdoing and instead attributed the youth’s death to his own ‘mental weakness’. Inevitably, such views are bolstered by the ongoing existence of the colonially-introduced Section 377 and associated police acts which serve to criminalise same-sex relations and enshrine binary, heteronormative gender ideals into Myanmar’s legal system.

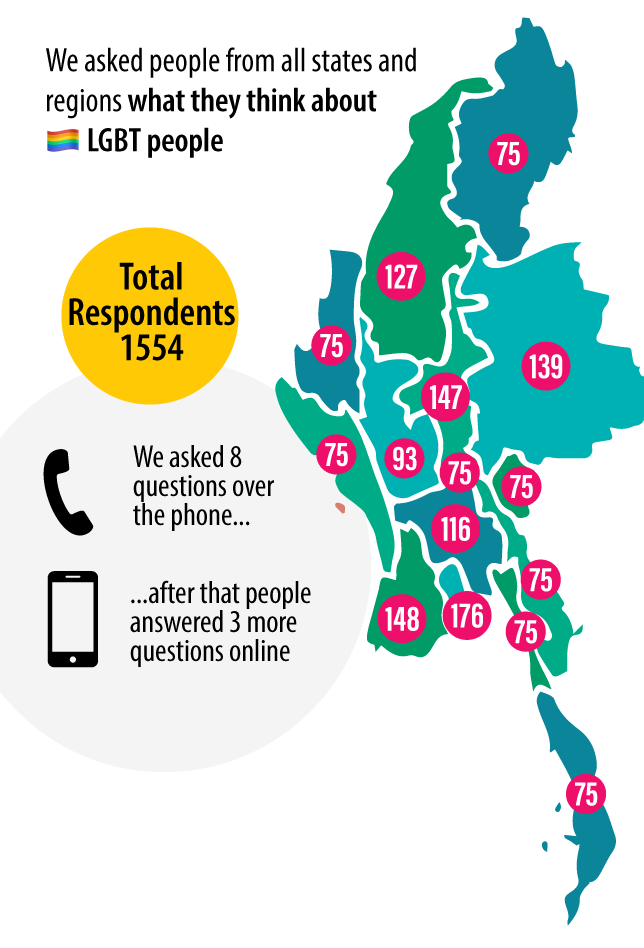

The objectives of Colors Rainbow and &PROUD’s research were two-fold: i.) to produce Myanmar’s most comprehensive stand-alone study on public attitudes towards LGBT people; and ii.) to inform community-led campaign strategies to promote greater acceptance and support of the LGBT community. The study was conducted by mobile phone using the proprietary research panel of a locally contracted research agency, and respondents were representative of the population across demographics such as gender, age, location and education.

By far the most salient findings for LGBT activists will be the fact that 74% of respondents did not agree with the criminalization of LGBT identities—indicating that if handled sensitively, dismantling Section 377 and the relevant Police Acts will not be a publicly unpopular action for the government. Even more reassuring is the finding that 81% of people agree with the statement: “I believe LGBT people deserve equality and equal treatment just like anyone else in Myanmar”. This finding is particularly interesting to note alongside the fact that 31% of people did not agree with the more personal statement “I accept and support LGBT people”. We can conclude that despite personal prejudices, a belief in equality and equal treatment for all people seems to take precedence.

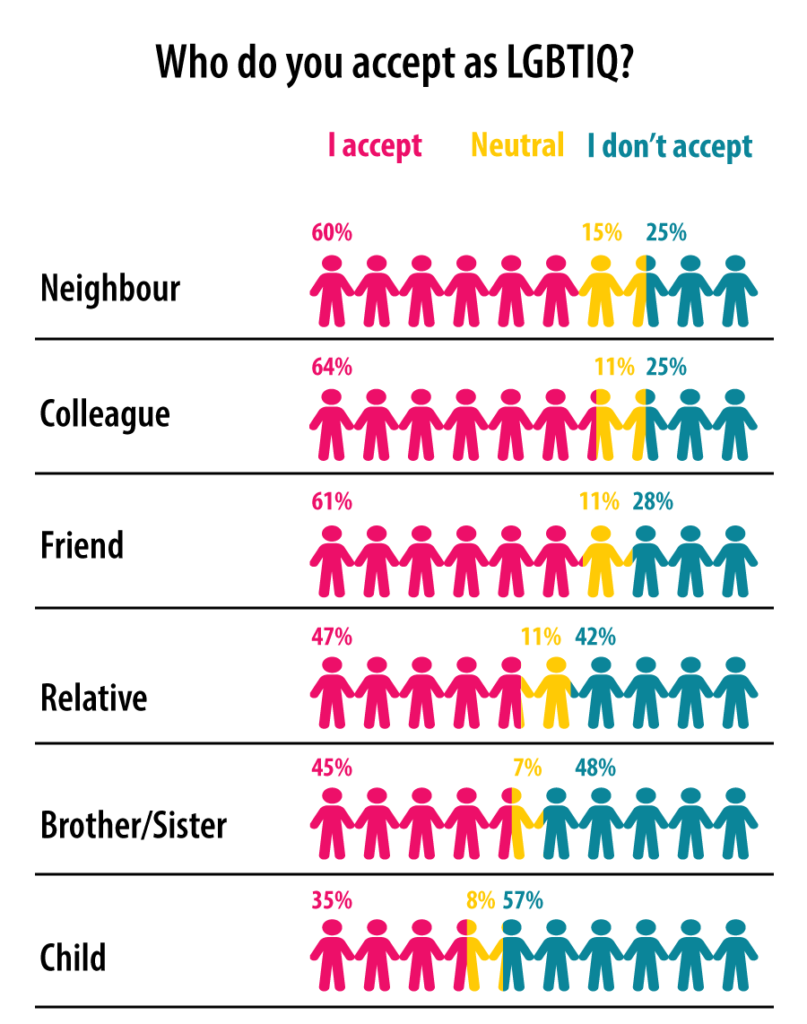

Indeed, it must be noted that people were more willing to accept LGBT people in an abstract sense, but less so when the person in question was closer to home. One in two respondents expressed it would be completely unacceptable if their own child was LGBT, while a similarly high number indicated an unwillingness to accept an LGBT sibling.

While the results are reassuring for LGBT activists insofar as that they demonstrate solid public support for legal reform, they also unearth some unignorable tensions. Most glaringly, the lack of support and acceptance for LGBT children or family members reveals that for many, LGBT people are only acceptable at arm’s length. This demonstrates a need for advocacy and campaign strategies that can emotionally compel people to unconditionally support and welcome LGBT people in both their public and private lives.

Furthermore, while it’s a powerful tool, demonstrable public support alone will not be sufficient to achieve legal reform. Separate lobbying will need to take place behind the scenes with Bill Committees and parliamentarians before substantive actions can be taken. Led by Colors Rainbow and the LGBT Rights Network, this work is indeed already underway, but the process is not as easy as convincing lawmakers to strike a line in the rule books. For example, a major issue in the Myanmar Penal Code is that the current definition for rape (Section 375) only holds in heterosexual circumstances, with same-sex intercourse being illegal whether consensual or not. Thus, if consensual same-sex relations are decriminalized, lawmakers will need to redefine rape to include non-consensual intercourse between people of the same sex, which means that three intertwined sections in the Penal Code will require examination and amendment.

What is clear in the road ahead is that securing human rights for Myanmar’s queer folk will require attention being paid to both social and legal realms. In battlefronts for queer equality across the globe, negative voices and violence can and do drown out quiet support and acceptance. Nevertheless, this data indicates that there is in fact widespread belief in the inherent right for LGBT people to be treated with dignity and respect. Myanmar’s LGBT community needs to find ways to activate positive voices within the general public and amplify human faces and stories within the debate.

A full analytical report detailing all the findings of the survey will be released later this year in both Burmese and English language.

* In Burmese, the word for intersex is not widely understood by the general public, and intersex issues have not been mainstreamed into the existing LGBT movement. As such, this study was regrettably not able to cover intersex experiences and realities in a cohesive or comprehensive manner. Nevertheless, both Colors Rainbow and &PROUD are working towards awareness-raising, advocacy and programming that addresses the needs of intersex people and encourages their participation in the movement.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss