From our tiny 6-seater plane, the 122 islands that make up the Houtman Abrolhos are deceptively close to the Western Australian coast. Taking off from Geraldton airport in a small GA8 Airvan, it seems only a matter of minutes before the first patches of coral appear in the opalescent sea-green waters below us.

Our plane’s shadow passes over the southern edge of the Houtman Abrolhos islands. Image: Natali Pearson

These islands lie some 80 kilometres from the Australian mainland, and while such distances are easily navigable in a small plane, they may as well have been a death sentence for anyone wrecked here.

Danger ahead

The name alone suggests marine peril – Houtman was the Dutch captain credited with discovering the islands in 1619, while Abrolhos is believed to refer to a Portuguese phrase for ‘open your eyes’ (abre os olhos). Today, the Houtman Abrolhos make for spectacular vistas from the air, but for seafarers of the past, these shallow seabeds and low-lying islands were very dangerous.

Over crackling headphones, our cheerful pilot Josh points out at least half a dozen known shipwreck sites, including the Zeewijk (1727), Ocean Queen (1842), Ben Ledi (1879) and Windsor (1908).

The Ben Ledi, one of many wrecks in the Houtman Abrolhos. Can you spot it? Image: Natali Pearson

Our chartered ‘shipwreck tour’ of the Houtman Abrolhos had been organised as part of the IKUWA6 international maritime archaeology conference , held at the Western Australian Maritime Museum in Fremantle in December 2016. This was the first time IKUWA had been held in the southern hemisphere, and it is clear that organisers were keen to showcase Australia’s significant maritime histories and amazing natural landscapes to conference delegates.

For those fortunate enough to participate in the ‘shipwreck tour’, myself included, the main drawcard was the opportunity to see Morning Reef and nearby Beacon Island – site of the 1629 Batavia wreck. My interest in this wreck had been stimulated by Mike Dash’s Batavia’s Graveyard: The true story of the mad heretic who led history’s bloodiest mutiny (2002), which I chanced upon in Sydney University’s Fisher Library (there is much to be said for browsing a shelf rather than an electronic catalogue).

History isn’t usually as neat as this. The story of the Batavia not only has well defined heroes and villains, but a distinct beginning, middle and end that makes it ideal for narrative history ~ Mike Dash

The Batavia was a massive Dutch East Indiaman – greater in length than an Olympic swimming pool – that crashed on her maiden voyage from Amsterdam to the Dutch East Indies.

What happened next is the stuff of horror movies: although most of the passengers survived the initial shipwreck, the presence of a man named Jeronimus Cornelisz would have soon made them wish otherwise. Over the next few months, 125 of these survivors would be murdered by Cornelisz and his band of thugs in a gruesome rampage from which there was no escape.

Of the 300-odd people who departed Holland on the Batavia, only 122 would make it to their final destination.

Wine and women, murder and mayhem

Cornelisz was a former apothecarist who had joined the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or VOC) to escape debts and a difficult family life in Holland. Not only was he the most senior VOC representative on the islands (all other senior officers having gone in search of help), but he was extremely charismatic, articulate and persuasive.

Cornelisz subscribed to a set of religious beliefs that valued the pursuit of sensual pleasures above anything else. To this end, he collected as much treasure as he could from the wreck – silver coins, gaudy clothes, gallons of wine – and set up camp on Beacon Island to await rescue. It is clear that he intended to enjoy the wait.

View of Beacon Island, also known as Batavia’s Graveyard, from our plane. Image: Natali Pearson

In a particularly terrifying development, Cornelisz also exerted sexual authority over the surviving female passengers. Lucretia Jansz, a renowned beauty who had been travelling solo to join her husband in the Dutch East Indies, had resisted Cornelisz’s advances since the ship’s departure from Holland. He exercised revenge by restraining Jansz in his tent for his own personal use.

But Cornelisz’s pursuit of pleasure went far beyond wine and women: murder and carnage soon became a common event on these islands. By the time help arrived three months later, 125 people had been killed – drowned, bludgeoned, stabbed – at the hands of Cornelisz and his group of supporters.

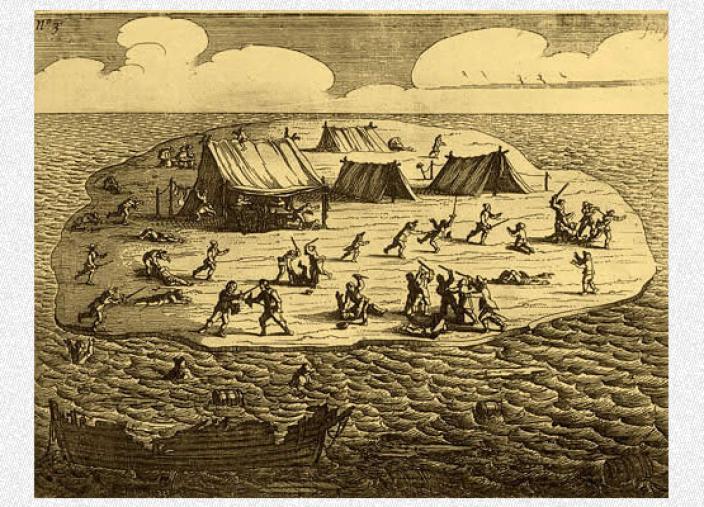

Engraving of the massacre that followed the Batavia shipwreck – from the Jan Janz 1647 edition of Ongeluckige Voyagie. Image: Western Australian Museum

From the air, the Batavia’s impact on the coral reef is still evident, a light turquoise patch amidst the darker blues and greens revealing where the ship made contact almost four hundred years ago.

A turquoise patch (centre) amidst the dark blues and greens reveals the site where the Batavia collided with the reef in June 1629. Image: Natali Pearson

For the several hundred survivors who washed up here, the Australian mainland would not have even been visible. Even before Cornelisz began the killings, their isolation and despair would have been overwhelming.

The Houtman Abrolhos islands may be a beautiful day trip for tourists, but the unrelenting sun, lack of adequate cover and limited fresh water would have made life incredibly difficult for survivors of the Batavia. Image: Natali Pearson

The Batavia was under the command of VOC Senior Merchant Francisco Pelsaert when it left Holland in late 1628. Part of a larger fleet of VOC ships bound for Batavia (now Jakarta) in the Dutch East Indies, the Batavia was carrying cargo for the fledgling colony – including silver coins and a massive sandstone portico which doubled as ballast – and over 300 crew, soldiers and passengers.

A replica of the portico on display at the WA Shipwrecks Museum in Fremantle, adjacent to a portion of the excavated Batavia hull. The original portico is in the Shipwrecks Gallery at the Museum of Geraldton. Archival research indicates the portico was destined for use either at the Land Port or the Waterport for the Castle at Batavia. Image: Natali Pearson

Tensions between Commander Pelsaert and his Captain, Ariaen Jacobsz, began to simmer early in the voyage during a scheduled stop on the Cape of Good Hope.

While there, it became clear that there was not much love lost between Pelsaert and the ship’s captain Adrian Jacobsz, whose drunken behaviour extracted a very public scolding from Pelsaert. This was to sow the seeds of disaster. ~ WA Museum

Jacobsz wasn’t the only crew member to resent Commander Pelsaert; enigmatic Junior Merchant Jeronimus Cornelisz was also resistant to Pelsaert’s authority. Once the Batavia left Africa and began to make its way east across the Indian Ocean, this dissent began to solidify into plans for a mutiny. These plans were thwarted when the Batavia was wrecked in the Houtman Abrolhos late one night in June 1629. More than 250 people survived the wreck and managed to salvage some supplies, albeit limited, of fresh water and rations.

Despite the isolation of the wreck site and the fact that nearly four centuries have elapsed, an abundance of archival and archaeological evidence means that a great deal is known about the horrifying events that ensued after the Batavia was wrecked.

For historians, one of the most important documents is the Pelsaert Journal, which Commander Pelsaert began the day after the Batavia was wrecked.

Reproduction of the Pelsaert Journal at the WA Shipwrecks Museum in Fremantle. Image: Natali Pearson

As the most senior VOC representative and ultimately responsible for cargo and passengers (in likely order of priority), Pelsaert had kept a diary since the Batavia’s departure from Holland in late 1628, but this early version was lost in the ship’s wrecking. The extant journal, much of which is based on confessions extracted under torture, documents Pelsaert’s decision to take the remaining longboat and, together with Captain Jacobsz and most of the senior officers, set off on a desperate search for fresh water.

Finding none, and realising they were now closer to Java, their original destination, than to the ship’s wreck site, Pelsaert and his small crew made the decision to seek help from authorities in Batavia rather than return to Beacon Island.

First wrecked, now abandoned

For the hundreds of people left behind, Pelsaert’s decision looked like abandonment. First wrecked and now deserted, they were now faced with the horror of being marooned on these islands indefinitely.

Thus began Cornelisz’s reign of terror.

Together with his band of henchmen, many of whom were the same men who had previously indicated support for a mutiny, Cornelisz set about systematically eliminating survivors. This was, initially, a strategic move – rations were limited and Cornelisz was determined to ensure his own survival.

Using a small boat, some survivors were dumped on nearby islands under the pretence of looking for fresh water – the assumption being there was no water, and that they would be stuck there until they perished. Others were drowned or bludgeoned to death. One infant, recounts Dash, was murdered by poison (Dash contends that this is the only murder Cornelisz carried out with his own hands).

These killings had initially been motivated by survival and the desire to minimise demands on the remaining rations. But at some point, the killings turned into sport: a reprieve from boredom, perhaps, or a deranged response by those in control to the unrelenting sun and ever-diminishing prospects of rescue.

After three months of killings, Cornelisz was eventually captured by a small group of survivors led by soldier Wiebbe Hayes. Hayes, who will undoubtedly occupy one of the hero roles in Russell Crowe’s forthcoming movie about the Batavia, was one of a small group of survivors previously abandoned by Cornelisz on a nearby island (now known as West Wallabi island) in a supposedly hopeless quest for fresh water.

Not only did Hayes and his fellow survivors find fresh water and plentiful food (including wallabies, seals and birds), but, upon realising the mayhem that was unfolding around them, they also constructed a small fort as protection against Cornelisz.

There was a great deal of excitement in our plane when we spotted this fort from the air, followed by astonishment at its size (tiny) and the ability of the survivors to source the construction materials (coral) on such a desolate island – an enduring, material testament to their will to live.

Wiebbe Hayes’ 1629 fort on West Wallabi Island remains standing to this day, and is significant for being the earliest European building in Australia. Images: Natali Pearson

Rescue and retribution

In a remarkable twist of history, the capture of Cornelisz coincided with Pelsaert’s return from Java aboard the rescue ship Sardam. Given that three months had elapsed since he first set off in search of water and assistance, Pelsaert may well have expected to find no survivors of the Batavia – or maybe he did expect to find some survivors, notwithstanding a few deaths caused by dehydration or starvation.

But Pelsaert could never have anticipated the carnage that had taken place at the hands of the Junior Merchant and his cohort.

Confessions were extracted under torture, and punishment was harsh and rapid. Many of the mutineers, including Cornelisz (deemed too much of a risk to be placed aboard the Sardam), were executed using hastily-constructed gallows on Seals (now known as Long) Island. Two mutineers were abandoned on the Australian mainland, and the rest were taken back to the Dutch East Indies for trial and execution.

Bringing the Batavia to a wider audience

Re-discovered and first excavated over 40 years ago, the Batavia continues to provide research opportunities for archaeologists, anthropologists and historians. Under the auspices of the multi-disciplinary Australian Research Council Linkage Project, Shipwrecks of the Roaring 40s: A maritime archaeological reassessment of some of Australia’s earliest shipwrecks, researchers are now using new technologies and new research questions to interrogate the Batavia site (and other previously-excavated Dutch wreck sites of the 17th century in Australian waters).

As part of this project, steps have been taken to bring Beacon Island to a much wider audience than the remoteness of the Houtman Abrolhos would otherwise permit. Some of the results of these efforts are on display at the Western Australian Maritime Museum’s ‘Travellers and Traders’ exhibition (on show until 23 April 2017), where museum visitors are able to experience Beacon Island in a virtual environment through Beacon Virtua.

Staff at WA Maritime Museum demonstrating Beacon Virtua to IKUWA conference delegates. Image: Natali Pearson

This remarkable technology, developed by Curtin University’s HIVE (the Hub for Immersive Visualisation and eResearch), allows the public to tour Beacon Island, including its jetties, fishing shacks (now demolished in recognition of the archaeological significance of the site) and several grave sites. Nor do you have to visit the Museum to experience this technology – it is also accessible from your desktop here.

As this introductory video demonstrates,

The graves have been reconstructed through a technique called photogrammetric 3D reconstruction, a process which uses multiple photographs of an object to build an accurate and detailed 3D model of it. Beacon Virtua presents the island as it was in 2013, using audio and photography captured during multiple expeditions to the island to preserve this period in its history. In 2013 there were around 15 small shacks located across Beacon Island, originally used by the fishing community. These shacks have been recreated as 3D models, which can be explored inside and out. Around the island are photographic panorama bubbles offering 360° views of the island. These bubbles have been captured using a special panoramic photography process – stepping inside a bubble allows you to see the island from that point exactly as it was in 2013.

The use of 3D photogrammetry and virtual simulation technology to enable greater public access to shipwrecks and other underwater cultural heritage is an exciting – albeit funding-intensive – development not only for maritime museums but for museums (and their visitors) more generally.

IKUWA conference delegates Dr Lucy Blue (Senior Lecturer in Archaeology at the University of Southampton) and Patrick Baker (WA Museum’s shipwrecks photographer) experiencing some of HIVE’s incredible technology. Baker took many of the original photographs in the 1960s that are now being used to digitally re-create the wreck. Image: Natali Pearson

Requiring less funding, but just as much enthusiasm and innovation, is the work of Western Australia’s Museum of Moving Objects (MoMo), which has also been instrumental in bringing the story of the Batavia to a wider audience. MoMo is a ‘museum without walls’ that brings archaeology and history to communities including schools, aged-care facilities, ferry terminals, airports – anywhere – through mobile workshops. Challenging the idea of what constitutes a museum, MoMo has brought a number of maritime archaeology workshops to its audiences, opening up a world of possibilities for people physically incapable of diving such as the young, elderly or disabled.

One of MoMo’s first ‘Archaeology in a Shoebox‘ workshops looked at themes of annexation and commemoration in relation to Dirk Hartog, but MoMo organisers realised the response was noticeably gendered: while women responded well, interest amongst men was limited. In response, MoMo curators developed a workshop aimed specifically at engaging men: ‘Murder and Mayhem’, focused on the Batavia. To no-one’s surprise, this workshop was a resounding success, and generated more questions than they have ever had in any other workshop.

Alternative narratives

Despite numerous books, documentaries and even an opera, the tragic and astonishing tale of the Batavia has made a surprisingly limited impact on the Australian consciousness. As Australian maritime archaeologist Jeremy Green has reflected, ‘It is a story that is well-known amongst West Australians but, for many reasons, people in other states aren’t as well acquainted with it’.

Perhaps this is because the Batavia displaces the stories we tell ourselves, the ones that place Australia’s Eastern seaboard, and not the West coast, at the centre of frontier histories.

But is it more than simply a question of the east vs west?

Perhaps the Batavia unsettles many of the accepted tropes of colonial Australian histories: instead of invasion and displacement of Indigenous Australians by the British, this is a primarily Dutch story that takes place on Australian soil. Setting aside the (tantalising) question of what happened to the two mutineers abandoned on the mainland, the wreck survivors had no known interaction with Indigenous Australians.

Perhaps, as Sparrow asks,

The traditional narrative of white Australia posits the coming of the First Fleet as an almost natural development, the inexorable result of the British Empire’s growth. By contrast, the Batavia story, and contemplation of the Dutch presence in Australia prior to 1788, sets both England and the Australian continent itself on a different axis. It remaps the regional geography around Jakarta, and Amsterdam becomes more significant than London. We’re pushed into a multivalent history in which there are more actors and the outcomes feel somehow less preordained. The specific way that white settlement unfolded loses some of its inevitability.

The shipwreck tour to the Houtman Abrolhos was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for most of us, and undoubtedly the best conference ‘side visit’ I have participated in. Even the locals among us were dazzled by the beauty of these islands, and the uncomfortable realisation that we knew so little about what had taken place here.

As Beacon Virtua and MoMo’s Murder and Mayhem demonstrate, new technologies and ideas can provide the public with greater access to the significant historical and archaeological discoveries that continue to be made on remote Beacon Island and its surrounds. These innovations may, in turn, prompt a deeper appreciation of the possibility of alternative narratives in Australian – and Dutch, and Indonesian – histories.

East Wallabi island’s airstrip enables visitors to experience the remoteness of the Houtman Abrolhos from the ground. Image: Natali Pearson

The shelter shown here on East Wallabi island has been constructed to accommodate day-trippers. Image: Natali Pearson

***

Thanks to IKUWA6 conference organisers and presenters; staff at the WA Maritime Museum (including curator Corioli Souter) and WA Shipwrecks Museum who took the time to show us around the exhibitions; Geraldton Air Charters; Dr Andrew Woods at HIVE; Patrick Baker for making sure we had our 3D glasses on the right way; and the lively international delegates who participated in the Houtman Abrolhos shipwreck tour.

Natali travelled at her own expense.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss