Cambodians in outlying provinces were given an opportunity to watch live the most important verdict in the Khmer Rouge Trial to date prompting an outpouring of emotion, Julia Mayer writes.

This month marks a momentous event in Cambodia’s modern history, and the lives of its people, with the handing down of a final verdict by the Extraordinary Chambers of Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) in the first case concerning two surviving senior officials from the Khmer Rouge regime, Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan.

The Documentation Centre of Cambodia organised live screenings of the decision, held mostly in Buddhist temples and monasteries, in seven remote rural locations, with the aim of providing access to otherwise hard-to-come-by information. Screenings took place in the far-flung provinces of Stung Treng and Mondulkiri, the nearer but isolated districts of the Takéo, Svay Rieng and Kandal provinces, as well as Kampong Chhnang and Kampong Cham which have the largest concentration of Muslims in the country.

Briefings targeting ethnic minorities, marginalised peoples, ex-Khmer Rouge soldiers and cadre, villagers and school-aged students took place prior to the 9am pronouncement, which took one and a half hours to deliver. Following the verdict, forums were held for participants to express their reactions and opinions relating to justice, and the ongoing issue of healing and reconciliation.

Each venue had at least two Documentation Centre representatives present to guide the participants through the history of the Khmer Rouge Tribunal and case-specific content. Documentation Centre staff also distributed materials including copies of Khamboly Dy’s A History of Democratic Kampuchea (2007 DC-Cam), which is a now a staple textbook for all secondary students in Years 9-12. A book specifically about the founding case against the surviving Khmer Rouge officials, known as 002, was also provided, as was a booklet on the history of the ECCC, including a summary of the Trial Chamber’s original judgment in case 002/01 (which narrowed the scope of 002).

Elderly survivors from the Prek Phtoul commune in the south-western Takéo Province welcomed the news of the final verdict, in addition to the opportunity to discuss the hardships endured under the regime.

“I believe this is about Karma because they did bad deeds, they were very cruel,” said Mrs Srey Yeng, 71. She recalled how at eight-months pregnant, she was assigned hard labour as part of the ‘four-year plan’ (1977-1980) where improbable tonnes of rice were expected to be yielded from war-scarred territory. When her three-year-old daughter became gravely ill with disease-related malnutrition, she requested permission from the collective leaders to attend to her. “You are not a doctor. You just keep working. Your children are looked after,” she remembers one saying. Yeng lost a total of ten family members, along with her daughter who died shortly after this incident.

The estimated number of deaths from starvation, execution, disease and overwork, ranges anywhere from 1.7 – 2.2 million – just under a third of the population at that time. That suggests there is not a person living today who remains unaffected by the aftermath of the near four-year reign of terror. More than 40 years later, the yawning wounds of the era may have healed into palpable scars, though reconciliation has been met with a degree of incredulity and repudiation particularly among the younger generation.

“I have often shared my experiences with my grandchildren, but I am never quite sure they believe me,” said Mrs Sok Phy, 79, echoing others who have found it a struggle to explain the extreme oppression endured.

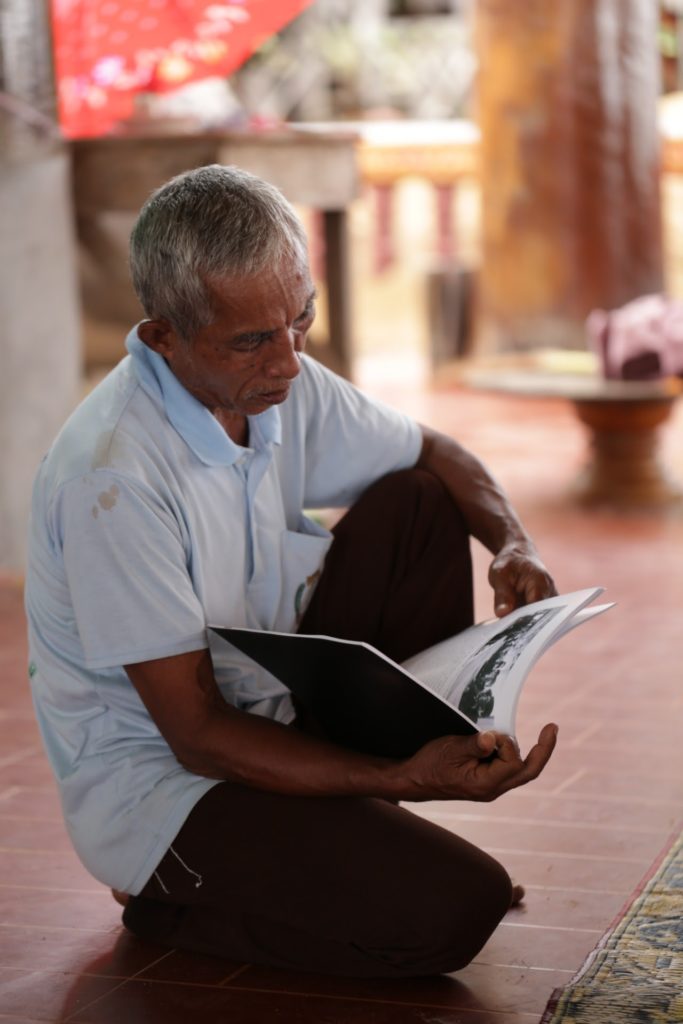

Accompanied by her grandchildren, Pech Keat, 72, points to a page in her copy of A History Of Democratic Kampuchea provided at the screening. “During Khmer Rouge regime, I worked like them. It was unimaginable hardship,” she tells them, hoping that the grainy, muted grey and brown photographs will work in some way as proof of her nightmarish existence under the regime.

While the Khmer Rouge Tribunal has been heavily criticised for lengthy delays, arguably its greatest impact has been on valuing education as a means of genocide prevention.

“One of the most significant effects has been in the form of generating discussion and raising awareness,” said Youk Chhang, Executive Director of the Documentation Centre of Cambodia. Additionally, revealing evidence to explain what happened during the period, in order to understand how it could ever have happened, highlights the importance of justice both in the present and for the sake of the future.

“How can a country profess to have the courage to take on the problems of the present and future, if it does not even have the courage to face its past?” asked Chhang who has been instrumental in getting a genocide studies program up and running to heal a forty-year division between perpetrators and victims.

To date, over half a million people have visited the tribunal, with a large percentage being mostly school-aged students from rural areas participating in the outreach program. The Khmer Rouge Study Tour is a one-day affair where interested parties such as NGOs and students visit the ECCC, the nearby Choeung Ek ‘Killing Fields’ and the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, the Khmer Rouge’s most notorious prison-security centre codenamed S-21. For the elderly and for those marginalised by distance and other circumstances, the live screenings importantly provided an opportunity to work toward healing and reconciliation within their own small communities, still very much plagued by social issues.

“I do not want personal compensation,” says 51-year-old Mr Dang Sheang. “What I hope to see are the kind of education measures being put in place now, which will continue to serve as a reminder to younger generations to protect the country from mass atrocity.

Julia Mayer is a Masters of Museum and Heritage Studies student at the Australian National University. She has lived in Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam and South Korea, and has written extensively on traditional arts, performances and cinema in the region. She is also the Asia Correspondent for Metro Magazine Australia.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss