Before there was any academic interest on female entrepreneurship and long before women were conceived of as girl bosses in public consciousness, women were central to the domestic Vietnamese economy.

Low-class women dominated the marketplace. They thrived on the hustle and bustle of the most prosperous ports in Southeast Asia. They grew crops and livestock, wove clothing, made handicrafts and pottery, and transported their goods to be sold at the local market. They also held the purse strings and were the serious buyers in the marketplace. From Hội An to Hà Nội, the business of buôn bán or “buying and selling” was an almost exclusively female phenomenon in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Despite a wealth of primary sources, historical scholarship has neglected the experiences of Vietnamese merchantwomen for centuries. Aside from one passing mention, the literati elite could not care less about what female merchants got up to. Thankfully, we have stele inscriptions, oral tradition, and the memoirs of foreign male visitors to help piece together their narrative.

Thus far, the narrative has been underwhelming. Historians have traditionally used Vietnamese women as a metaphor for the nation. If they did not fight against foreign invasion, there was no point talking about them. Hence, while there are hints of their presence scattered across books and journal articles, the only full-length publication on women entrepreneurs in Vietnamese history (aside from a small blog also written by me) is an unpublished conference paper by George Dutton.

So who were these women? How did they dominate local trade and how did their economic role shape their livelihood and their communities?

The early modern period in Vietnam was a tumultuous time punctured by decades of civil war and political upheaval. The three ruling houses that emerged – the Mạc, the Trịnh, and the Nguyễn – fought one another and divided the country.

Map of Vietnam circa 1650 shows the territories of rival rulers. Sourced from Wikipedia. (Public domain)

During war, men were conscripted for the military or for corvée labour, forcing their mothers, wives, and daughters to step up and become the breadwinners of their family.

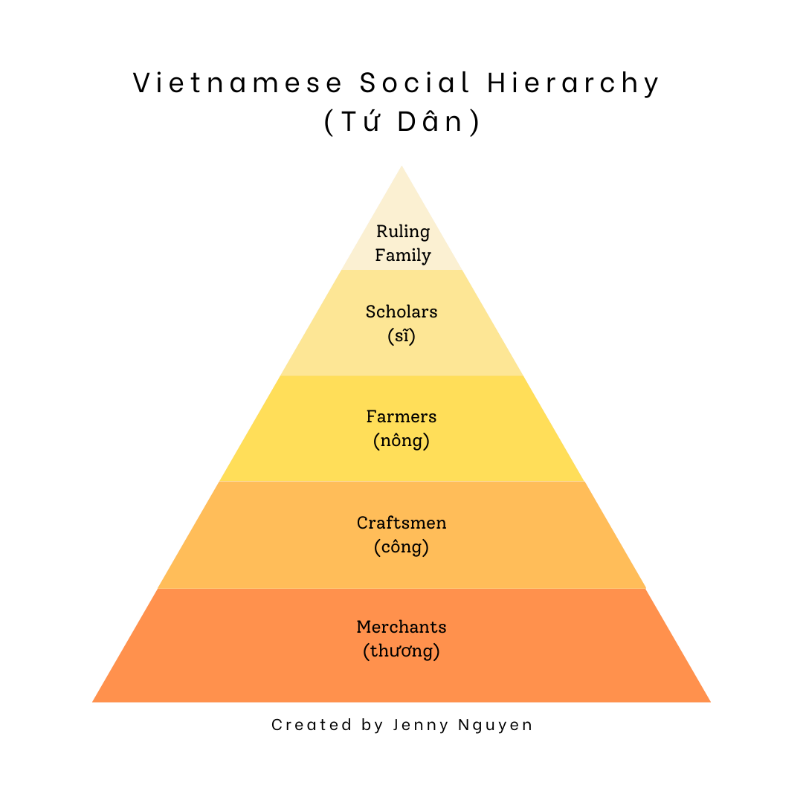

Even during times of peace, market ventures still fell within a woman’s domain. The Confucian social hierarchy elevated the exclusively male class of scholars (Sĩ) to the top and demoted merchants (thương) to the bottom. Many men dedicated themselves fully to studying in the hopes of one day passing the imperial civil service examinations and bringing honour to their family. This meant that they were completely dependent on the entrepreneurial abilities of their mothers, wives, and daughters. On the other hand, merchants were vilified as shady swindlers who profited off the back of someone else’s hard work. The lack of social prestige accorded to merchants left the markets wide open for women to fill.

The Confucian social hierarchy places scholars at the top and merchants at the bottom. Created by Jenny Nguyen.Although these factors facilitated the rise of a class of female entrepreneurs, they also put an enormous strain on women. It was physically demanding to be out in the fields, weaving and spinning or creating handicrafts, and bartering with potential customers whilst raising children.

Surviving folk verses sing the chorus of generations of businesswomen who found their economic role a chore. Their days were repetitive. Their tasks had little meaning. One reads:

Is this my fate as a young girl in her prime?

(Phần em con gái xuân xanh)

Days spent at the market and nights spent spinning and weaving at home?

(Ngay thời buôn bán, đem củi cảnh trong nhà).

Told from the perspective of a young woman, she, and those she represented, felt that they had to weave and sell silks and cloths, or else their family would starve. It was hard for some to find joy in running a business when it needed to be done.

Despite being burdened, women proved to be impressive entrepreneurs. They were extremely hardworking. At the end of the 18th century, English statesman Sir John Barrow noticed that women did everything. They repaired cottages and vessels, conducted their business on boats, and were heavily involved in all phases of silk and cotton production. He added that

the activity and the industry of the women are so unabating, their pursuits so varied, and the fatigue they undergo so harassing, that the Cochinchinese apply to them the same proverbial expression which we confer on a cat, observing that a woman, having nine lives, bears a great deal of killing.

Their hard work ethic meant that they were the backbone of their households and society – so much so that French horticulturalist, Pierre Poivre, surmised in 1749 that a man’s main goal in life was to never lift a finger while his wife did all the heavy lifting.

Female merchants were also renowned for their accounting skills and business acumen. They knew how to bluff and barter. When Dutch trader Jeronimus Wonderaer came to Đà Nẵng in 1602 to trade for pepper, he found himself constantly negotiating with a reputable female merchant who drove a hard bargain. He also found that he could only communicate with the Nguyễn lord through two elderly women – both of whom picked up Portuguese and Malay from their previous marriages to Portuguese men.

In fact, women merchants’ multilingual skills were in such high demand, and they were so good at what they did that foreign male traders often involved local women in their business dealings by temporarily marrying them. These mutually beneficial partnerships have a long history in Southeast Asia. A 14th-century Chinese account described Chinese sailors marrying Cham women for the duration of their stay even though these women already had husbands. The sailor received companionship, sustenance, and shelter whereas the woman was rewarded with gifts or money for assisting the business of the vessel at large and developed lingual and cultural fluency. Once the men left shore, the marriage autonomically dissolved. When the next shipment arrived the following year, the process began afresh with the same women marrying different husbands. This practice continued well into the early modern period.

Although these arrangements were mutually beneficial, as time passed, Vietnamese women were condemned and stigmatised for going about their daily business. A strong female public presence and their willingness to approach strangers offended the Christian and Confucian patriarchal views that foreign male visitors held. Female entrepreneurs were interpreted as not only hard working, but also working hard at prostituting themselves.

Spanish Dominican missionary Domingo Fernández Navarrete wrote in 1667 that women felt no shame approaching men as soon as their ship docked into shore. Italian Jesuit missionary Giovanni Filippo de Marini accused the debased marketplace for corrupting Vietnamese women and allowing them to “lose themselves… [and] prostitute themselves shamefully and brutally without even being solicited, in the hope of drawing some use, however mediocre it might be.” The Chinese monk Da Shan further complained in 1694 that the freedom female entrepreneurs enjoyed reduced the moral integrity of the people and country. By the end of the 18th century, English traveller George Staunton assumed that women were “transferred on easy terms and with little scruple” due to the prevalence of sexual relations between foreign tradesmen and Vietnamese women.

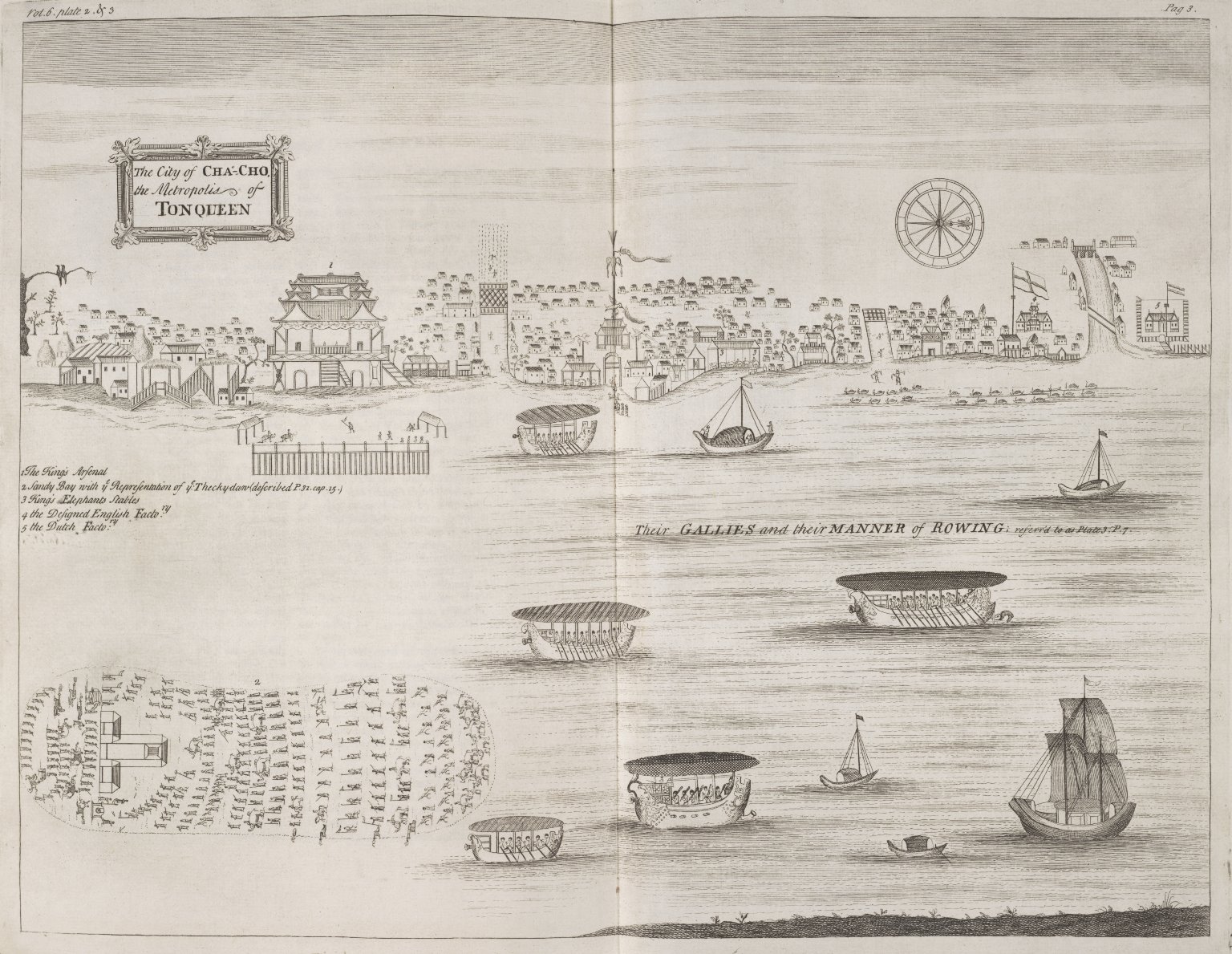

Painting of Ke Cho City, the capital of Dong Kinh (Cha-Cho City, the metropolis of Tonqueen) painted by Samuel Baron in 1685, printed in A Description of the Kingdom of Tonqueen and published in 1686.

Despite reports that female merchants were extremely loyal business partners, male travellers warned each other that there were more to these women than meets the eye. They could be a lot more conniving than they let on. Vietnamese women, especially those dealing in currency exchange, gained a reputation for being just as cunning as the most notorious stockbrokers in London. A Chinese merchant warned:

There are many women who come to the markets. The women, with ratty hair, babble aimlessly. They deport themselves like great and powerful nobility, entering the gate in order to leave us with their areca. Always watch out.

The disrepute women entrepreneurs suffered in the eyes of foreign male visitors and the Vietnamese Confucian elite aggravated the burden they had to bear. Already physically exhausted from managing a household, running a business, and looking after children, the ingratitude and lack of credit women received took a real emotional toll. Some folk verses comment on the hardships women faced, for example:

Respecting the rule of fidelity, I married nine husbands.

(Chính chuyên lấy được chín chồng)

Rolling them into balls, I put them in a jar and carried it with a shoulder pole.

(Vê viên bỏ lọ gánh gồng đi chơi)

Who would have thought that the suspending frame would break and the jar would fall?

(Ai ngờ quang đứt lọ rơi)

Out crawled the nine husbands scattering in nine different directions.

(Bò ra lổm ngổm chín nơi chín chồng.)

Using temporary marriages as a metaphor, the verse indicates the sheer number of responsibilities women had to juggle. It also points out the irony of the circumstances many women found themselves in. Expected to work to the bone and balance multiple roles, it was only a matter of time before they crumbled under the pressure.

Despite the obstacles, women entrepreneurs of early modern Vietnam earned a generous income. They bought and controlled property. They donated to temples and shrines, enabling a wide variety of faiths to flourish. They funded the building of roads and bridges and the expansion of markets, supporting other women entrepreneurs. Their donations cemented their legacy, ensuring that they were honoured and venerated for generations to come. In fact, their contributions were fundamental to shaping Vietnam’s early modern social, religious, and economic society.

Female merchants travelling to the markets in Hà Nội in the 17th century cemented the legacy of Princess Liễu Hạnh (pictured) as one of the most prominent female goddesses in Vietnam today. Sourced from 1906 woodblock publication, Tam vị thánh mẫu cảnh thế chân kinh (The Three Holy Mothers of the True Sutra)

When we reimagine early modern businesswomen in public consciousness, we see them as a precedent for modern female entrepreneurs.

They were the girl bosses resisting patriarchal norms before girl bosses were even a thing.

They are the example we should emulate.

But they are so much more than an archetype. For a long time, Vietnamese women have been mythologised as remnants of a subsisting indigenous feminist culture. An ancient national spirit ran in their blood. However, by placing them on a pedestal, we have neglected to study them as subjects of their own historical inquiry.

Although I cannot give a conclusive or holistic picture of how early modern Vietnamese women entrepreneurs lived or what their realities looked like, as a descendant of the class of female entrepreneurs who conquered the marketplace and made it their kingdom, I owe it to them to at least try to tell their story.

The author is grateful for the support of the Sydney Southeast Asia Centre and its residency workshops.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss