Our ideas on the infallible right to territorial integrity haven’t just caused a new rupture in Australia-Indonesia relations. They are increasingly outdated for today’s globe.

Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott is speaking like Leviathan, that absolute sovereign of Thomas Hobbes’ mind.

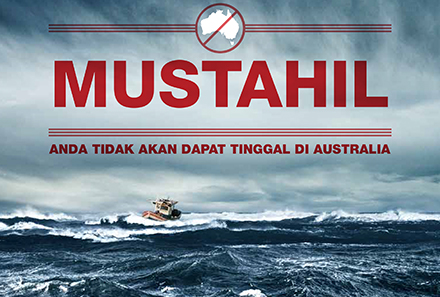

His hard-line stance on illegal boats and national borders is a rallying call to protect Australia’s sovereignty at all costs… even if it means paying those who he labels as the evil, criminal scourge behind the problem of people smuggling.

But Abbott and his government’s notion of sovereignty is a worldview increasingly out of touch with today’s world. And so in the latest Australia-Indonesia fallout over irregular migration, his comments about ‘stopping the boats’ leading to cordial neighbourly relations are simply too sincere to be ironic. Abbott told journalists on Tuesday:

The great thing about stopping the boats is that it has very much improved our relationship with Indonesia.

We will do whatever is necessary within the law, consistent with our standards as a decent and humane society, to stop the boats because… that’s the moral thing to do.

The only thing that really counts is: have we stopped the boats? And the answer is a resounding yes.

Stopping the boats at any cost (hook or by crook) represents a new high watermark in the obsession with Australia’s territorial integrity and the overinflated threat to it asylum seekers arriving by boat pose.

Abbott has cordoned off Australian shores to such an extent that now his government has allegedly paid people smugglers to return to Indonesia with the desperate human cargo they ferry. So desperate with the idea of border protection is this current government that Foreign Minister Julie Bishop issued her own salvo at Indonesia, telling it to fix theirs. Jakarta has expressed shock.

And so Australia’s obsession has once again got Indonesia offside. Having already antagonised our neighbour in the past with boat turn backs, this latest development will serve to put the relationship back where it all too often is – out in the cold.

Indonesia’s vice president Jusuf Kalla has now weighed in on the issue, comparing Australia’s alleged actions to bribery. He also said they were not according with “the ethics of international relationships”.

He has a point. But while the ethics are important, particularly in light of our responsibilities under international human rights conventions, Abbott’s position is just as revealing in that it shows how out of touch he is with the realities of global politics.

He privileges ‘domestic sovereignty’, or a focus on effective control within borders – that have simultaneously expanded and contracted through the projection of state power outside Australia’s domain and the excising of territory from the migration zone. But sovereignty, a fuzzy concept from the outset, can today also be seen as being ‘interdependent’, where global processes and flows, like the movement of people, begin to erode domestic control.

This is what Abbott is staring down now. But sometimes you simply need to learn to look at a problem in a different light. And sometimes staying in control comes with the ability to make concessions. After all, even Leviathan, to stay on the throne, had to give citizens rights and protection.

This is exactly what Indonesia, a post-colonial sprawl of many thousands of islands nervous about its own territorial integrity, did in the recent Asian migrant crisis. After maintaining a hard-line stance it agreed to settle some of the migrants – albeit only for one year.

Of course the less boats the better. But at the same time we need to recognise that strictly enforcing boundaries, which are a lot fuzzier than Abbott would have us believe, can be extremely counterproductive. These are complex issues.

I am not suggesting we open the ‘floodgates’, dissolve our borders, forget national security and give up sovereignty. But a more humane interpretation of the lines on a map would help countenance dealing with those boats that do cross in a more humane and progressive way.

Rather than ramping up some imaginary ‘red line’ and regional tensions, perhaps time and resources could be better spent sitting down with our neighbours and formulating a regional solution to smuggling. Showing flexibility on your own red lines has the virtue of demonstrating you are willing to listen when negotiating with others.

Abbott and Indonesia aren’t the only ones suffering from this one-dimensional view of sovereignty. Often overlooked in the great game of international politics are the people who are bouncing back and forward on our seas. Our obsession with domestic integrity and control means that many desperately seeking our protection find themselves at greater risk.

In today’s world perhaps one of the greatest tests to traditional ideas on sovereignty is the idea of the responsibility to protect; to intervene when states are a threat to their own citizens. It’s a controversial idea for obvious reasons. What’s not so controversial is the responsibility to protect when citizens flee states and seek refuge, or as in the case of Myanmar’s Rohingya, are effectively stateless.

These are the people who in seeking freedom, safety, the faintest glimmer of a future, often turn to people smugglers and make perilous journeys across the seas in the first place.

These are the people who we are increasingly turning away. And the more we doggedly assert our territorial integrity, the more we marginalise those who can’t or don’t have any borders to live within.

As an Australian passionate about global affairs and human rights, this leaves me cold. I not only worry about how we will be remembered tomorrow, but how we can claim any meaningful place as a responsible nation on the world stage today.

For once again our Prime Minister has shown his foreign policy hand isn’t a winner. In this case he hasn’t even got less Geneva, more Jakarta. He’s simply got more Canberra and a healthy dose of “stuff ya”.

James Giggacher is editor of ‘New Mandala’.

A version of this article was also published by ‘The Drum’.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss