The term “Chinese” is a capacious construct, referring today to political nation-states, an ethnic diaspora and a culture at once exported, exoticised and localised. When the British East India company established Penang, Malacca, Singapore and Dinding as Straits Settlements in 1826, they did so for trade and profit. Little did they guess that the “Straits”, referring to the Strait of Malacca and the Strait of Singapore, would be proudly adopted as the localised identifier for a cosmopolitan Chinese community that had settled for generations in the first three towns. Prior to the arrival of Europeans in South East Asia, the Chinese were a significant transnational presence in the region. Despite the ban on external trade intermittently until the first half of the 18th century, trade with China continued between Java, the Philippines and the Southern Chinese provinces of Fujian and Guangdong [1].

Interestingly, many Malaysians and Singaporeans of Straits Chinese descent trace their ancestry to the popular legend of the marriage of the Chinese princess Hang Li Po to Sultan Mansur Shah of 15th-century Melaka, where the men of her entourage intermarried with local women [2]. Perhaps this “self” functions as a kind of memorial dream of intermarriage and cultural fluidity, paying homage to a time when the term “Chinese” had not hardened as a racialised category imposed by the British colonial census, and later, the independent nations of Malaysia and Singapore.

Unlike Baba and Peranakan, “Straits Chinese” stands out for being a fully Anglophone term in its scope and origin. From 1852, the British colonial administration used it as a legal identification category, and was adopted by the community as a marker of status, wealth and the continuity of their traditions [3]. The Straits Chinese chose to differentiate themselves from later Chinese immigrants, who arrived in the region as labourers in the late 19th century.

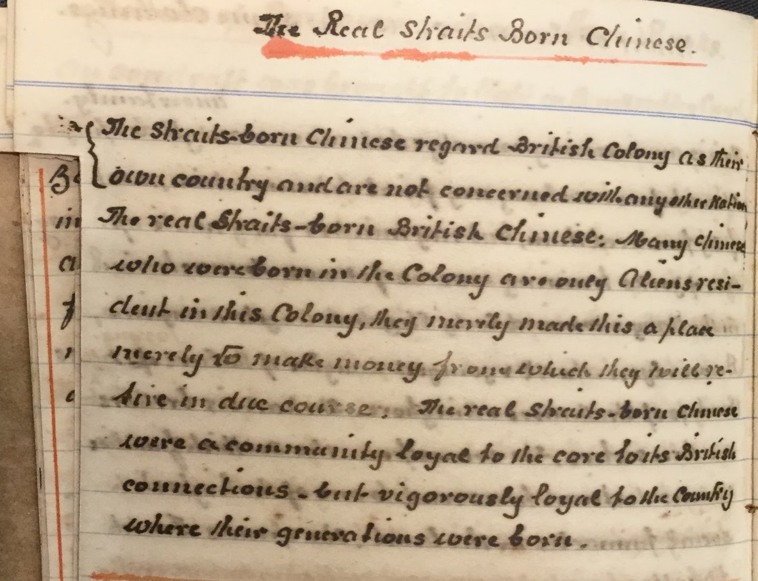

More importantly, they professed a strong sense of belonging to Malaya and a lack of patriotism towards China as an ancestral homeland, coupled with a simultaneous sense of loyalty as British subjects. Identifying as “King’s Chinese”, they insisted on self-representation in the Straits Settlements Legislative Council, and established the Straits Chinese British Association [4].

The Straits Chinese were also adept at marshalling cultural signifiers from Chinese culture and employing their command of English to signal their presence. At the 1887 Golden Jubilee celebrations in Singapore, member of the council Seah Liang Seah read out a congratulatory message inscribed in English on a Chinese-style scroll of crimson silk, bowing at the appropriate points with true rhetorical flair [5]. As a community, the Straits Chinese were among the first in Malaya to understand that self-translation of cultural traditions, and their command of English, led to empowered participation in Empire as a global circuit.

What is less well-known is the international outlook of the Straits Chinese in the lead-up to the Second World War. Prior to calls for self-governance following the defeat of the British in the war, the Straits Chinese harboured an understanding of civic participation that was remarkably cosmopolitan. Despite being proud British subjects, they also possessed a strong sense of belonging to Malaya. Their model of identity comes close to the European legal-moral definition of the cosmopolitan.With roots in classical Greek and Kantian philosophy, cosmopolitanism, strictly speaking, refers to the establishment of universal citizenship and a multinational system of political security [6].

Unfortunately, there are few Straits Chinese diaries and letters remaining from the 1930s. Those that survive are extremely important as they express immediate responses to the era that are not retrospectively ‘framed’ by the later perspective of independence movements, or by the proliferation of “Chinese” as a state-defined category.

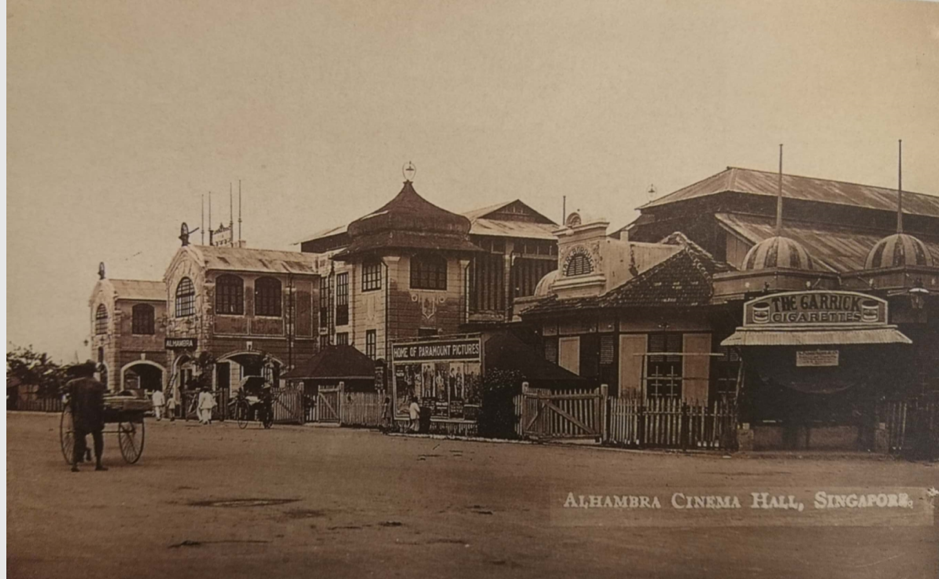

One of these primary sources is the notebooks of Tan Cheng Kee, a pioneer in Singapore’s entertainment industry, who owned the Alhambra, Marlborough, and Palladium theatres. (Great Peranakans). Held at the National Library of Singapore, these three slim volumes were written from approximately 1935 to 1939. They record Tan’s daily observations on an eclectic range of topics, from cold remedies to hunting big game and the morals of a good wife. Made up for the most part of anonymised remarks on personal and business acquaintances, Tan’s notebooks also contain a ongoing analysis of international events in the lead-up to the Second World War.

Published in Great Peranakans: Fifty Remarkable Lives, p. 146

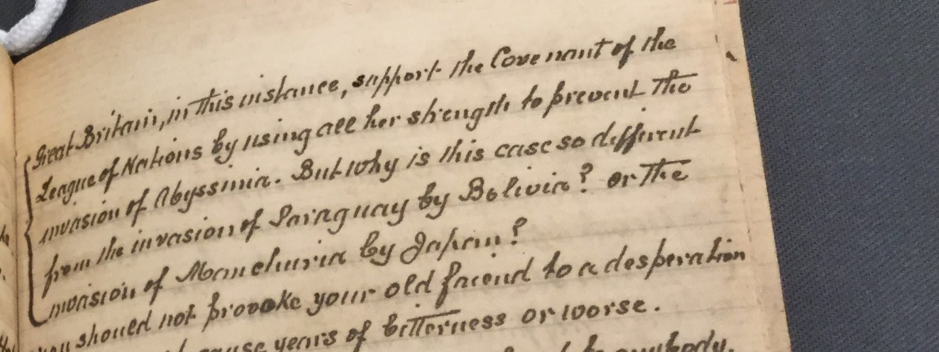

“The British Empire”, Tan wrote in the first notebook, “had been built up by conquests and aggressions”. In spite of such disapproval, he also conceded that a Monarchy under the Empire is necessary to “hold a strange collections [sic] of countries, peoples, governments”, indicating that he was attempting to formulate a concept of political organisation more capacious than the homogenous nation-state. In what may be regarded as an early comparative postcolonial perspective pre-dating the battle for Singapore, Tan refers to the League of Nations’ sanctions against Italy’s invasion of Abyssinia in 1935, and queries why similar actions should not be taken against Bolivia’s and Japan’s occupation of Paraguay and Manchuria respectively (see image below).

Donated by Peter Wee. Collection of National Library, Singapore. [B32454425G]

Donated by Peter Wee. Collection of National Library, Singapore. [B32454427I]

[1] Patke, Rajeev S., and Philip Holden. 2010. The Routledge concise history of Southeast Asian writing in English (Routledge: London), p.15 [2] In Reconstructing Identities: A Social History of the Babas in Singapore, Jürgen Rudolph traces in detail the academic scholarship relating to this legend, p.79 [3] Rudolph, Jürgen. 1998. Reconstructing identities : a social history of the Babas in Singapore (Ashgate: Aldershot), p.43 [4] Of interest is Song Ong Siang’s piece titled ‘The King’s Chinese: Their Cultural Evolution from Immigrants to Citizens of a Crown Colony’ published in the Straits Times Annual (1936). [5] Teo, John. 2015. ‘The Straits-Born British Chinaman: Imperial Rituals and the Peranakans.’ in Chong Guan Kwa, John Teo, Daphne Ang, Jackie Yoong and Alan Chong (eds.), Great Peranakans : fifty remarkable lives, p.50 [6] Heater, Derek Benjamin. 2002. World citizenship : cosmopolitan thinking and its opponents (Continuum: London), p.27; Kant, Immanuel et al. Political Writings. 2nd, enlarged edition, Cambridge University Press, 1991. Kant’s Politica Writings, p.47.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss