Indonesia’s ubiquitous network of neighbourhood associations, known as the RT/RW system (rukun tetangga/ rukun warga) is at the forefront of government efforts to manage the COVID-19 crisis. President Joko Widodo has identified neighbourhood leaders as “the key” to controlling the pandemic, tasking them with enforcing mobility restrictions in their areas and facilitating the distribution of economic assistance to eligible residents. Currently, the government is pursuing a strategy to replace costly region-wide lockdowns with enforcement of “micro” measures at the neighbourhood-level. Several regional administrations have already adopted this approach.

How have Indonesia’s neighbourhood leaders responded to these daunting tasks and what are the constraints they face? A new survey from the Greater Jakarta Metropolitan Area (Jabodetabek) shows that the RT/RW system is a promising avenue for grassroots interventions to manage the pandemic. Neighbourhood leaders enjoy high levels of public trust and a vast majority of residents acknowledge their authority to make a wide range of COVID-19 related interventions. However, RT/RW leaders’ concerns about legitimacy and conflict limit the extent to which they can intervene in their residents’ lives.

Mediating between state and society

Across Asia, neighbourhood associations are a valuable anchor for community-level policy interventions, due to their unique ability to mediate relations between state and society. Performing this task requires neighbourhood leaders to maintain a delicate balance between enforcing official directives from above and responding to residents’ wishes from below.

Neighbourhood leaders’ local legitimacy and granular knowledge of their communities enables them to extend the state’s reach into society and facilitate political control, especially in dense urban areas where communities are in constant flux due to migration. But, grassroots leaders’ capacity to enforce government policies depends on their ability to generate community goodwill—or at least, avoid residents’ ill will.

Indonesia’s RT/RW leaders have swayed between state and communities in this mediating role. Initially set up as coercive bodies by the Japanese occupying forces to mobilize resources during World War II, neighbourhood associations were repurposed by the New Order for mass surveillance, electoral control and ensuring public compliance with government programs.

Following the democratic transition in 1998, neighbourhood associations continue to be an indispensable part of statecraft in Indonesia. RT/RW leaders support routine administration by collecting resident data and verifying their eligibility for public services, socializing government programs, updating voter-lists and coordinating disaster responses. Initially, the coercive tasks assigned to the RT/RW leaders under the New Order were abolished but they have gradually assumed new social control functions, especially in anti-terrorism surveillance and management of local order.

While they are still routinely deployed for the business of the state, democratisation has made neighbourhood leaders more community-oriented in two ways. First, the government no longer exercises central control over these grassroots bodies through the Ministry of Home Affairs as it did under the New Order. Instead, each district or city government manages neighbourhood associations to meet local needs. Second, while RT/RW leaders were previously vetted by local bureaucrats, since 1998 residents have elected them freely, making neighbourhood leaders more accountable and responsive to their communities.

Despite the evolution of their role and functions, the basic hierarchical structure of these associations remains the same. In each village and hamlet across the country, sub-neighbourhood (RT) leaders are responsible for managing residents in a clearly defined housing cluster. Neighbourhood (RW) leaders supervise all RT leaders in their area and in turn report to village or hamlet heads. As under the New Order, RT/RW leaders are not part of the formal bureaucracy and do not receive a salary. However, several regional governments now allocate varying amounts of funds to support their operational costs.

Mobilizing neighbourhood authority for crisis response

Indonesia is not alone in relying on neighbourhood associations to manage a global health crisis. Governments across Asia, including Taiwan, Vietnam, China and the Philippines, have mobilized similar grassroots residential bodies for COVID-19 response, with varying levels of success.

The first clear set of instructions for setting up neighbourhood-level COVID-19 task forces in Indonesia were issued in April 2020. Simultaneous regulations issued by the Health Ministry and regional governments in the Jabodetabek area instructed RT/RW leaders to make similar interventions in their neighbourhoods, in coordination with village and hamlet-heads. These can be classified into two categories.

The first set of interventions assigned to RT/RW leaders are “community-wide” measures that impact all residents. These include provision of health information, disinfecting public facilities, distribution of economic aid, restriction of large gatherings and imposition of local lockdowns. The second are “targeted” interventions that involve identifying specific residents and imposing special restrictions on them, such as quarantining and reporting suspected patients to health officials, or restricting entry of those traveling back from high-risk areas.

How have neighbourhood leaders balanced the urgency of implementing these relatively invasive measures with the need to be responsive to their residents? I explored this question through an online survey of 1,047 residents in the Jabodetabek area which comprises of DKI Jakarta and its eight surrounding districts. The region is home to 30 million people, organized into a network of approximately 86,000 RT leaders serving under 15,000 RW leaders. The survey was administered in June 2020 when Jabodedabek had emerged as the epicentre of a COVID-19 outbreak and was placed under lockdown.

The online survey asked Jabodetabek residents to volunteer responses to two sets of questions. First, they were asked about their personal situation and the impact of COVID-19 on their lives. The sample of respondents was largely representative of the region’s population in terms of gender, age and income level. At the time of the survey, 10% respondents said they knew a confirmed or suspected case of COVID-19 in their neighbourhood. Over 60% respondents reported reduction in income due to Covid-19 and over 40% were receiving government aid.

Second, the respondents were asked about their views on their RT/RW leaders and the COVID-19 related measures taken by these leaders in their neighbourhoods. A vast majority of respondents (88%) said they knew their RT/RW leaders, mostly identified as men over the age of 40 in white-collar occupations or retired. Less than 6% residents said their RT/RW leaders were women.

The respondents also reported variation in the way their RT/RW leaders are chosen. Regional regulations (perda) that govern RT/RW elections in Jabodetabek stipulate that these leaders be chosen through a representative process by residents but allow village/hamlet authorities to conduct this process either through informal consensus (musyawarah/mufakat) or by formal voting. In the survey, 70% residents reported that their RT/RW leaders had been elected by voting, while others reported an informal consensus-based selection process or temporary appointments.

Public support for neighbourhood leaders’ Covid-19 role

The survey data show that on the whole, RT/RW leaders enjoy broad public support for making COVID-19 related interventions in their neighbourhoods (Figure 1). More than 80% respondents believed their RT/RW leaders had authority to make both community-wide interventions such as local lockdowns and ban on gatherings as well as targeted interventions like mandatory quarantine for suspected patients. However, residents overwhelmingly felt their RT/RW leaders were not authorised to refuse burial to COVID-19 patients or evict their families.

With regards to the distribution of government aid, most respondents believe that RT/RW leaders have the authority to identify deserving recipients. Despite reports about corruption of aid funds by some neighbourhood leaders, over 70% respondents trust their RT/RW leaders’ ability to fairly identify deserving recipients. This is a much higher percentage than respondents who expressed trust in formal government authorities to do the same, namely village/hamlet (50%) district (43%), provincial (46%) and the central government (54%).

Residents’ perception of RT/RW leaders’ wide range of authority is not driven by the pandemic as it also applies to order-making in everyday life. Over 80% respondents agreed that RT/RW leaders have the authority to evict troublesome residents, ban activities they deem immoral and prohibit controversial religious practices in their areas. Despite acknowledging their broad authority, however, residents do draw the line for RT/RW leaders’ influence on some issues. For example, a majority of respondents (85%) rejected the idea that RT/RW leaders were authorised to influence their residents’ political choices.

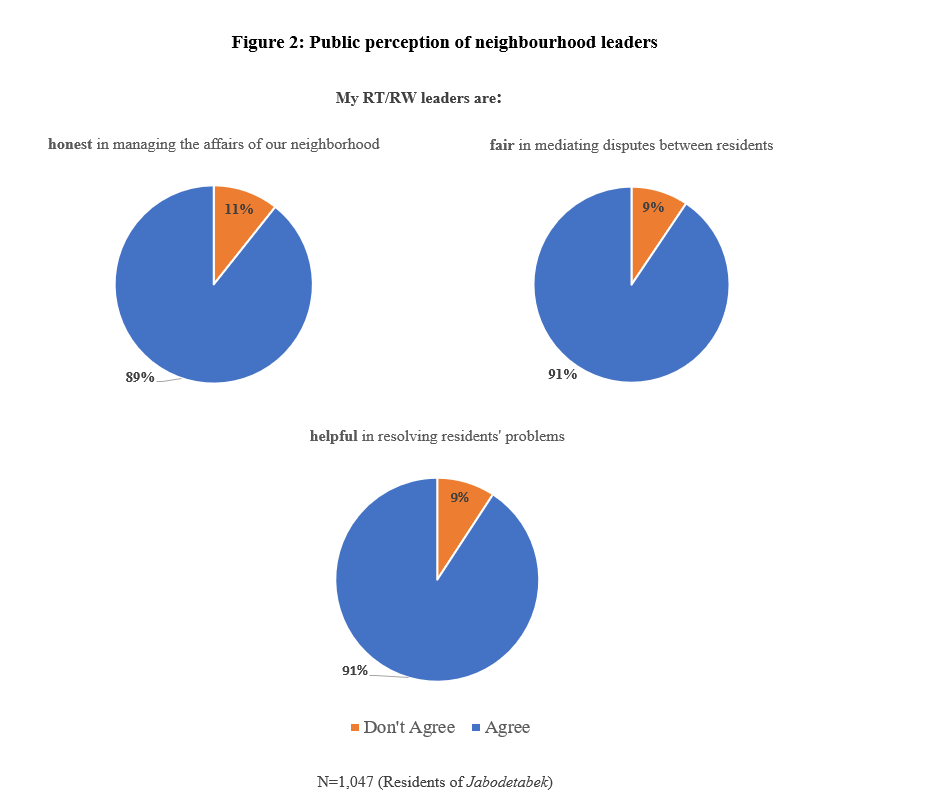

Residents’ understanding of RT/RW leaders’ authority appears to be rooted in their frequent and positive past interactions. Almost 90% of respondents, regardless of socio-economic status, described their RT/RW leaders as “fair”, “honest” and “helpful” in past dealings (Figure 2). This positive assessment is based on regular interaction between residents and their RT leaders, who are typically closer to their residents and more accessible than RW leaders. Over 60% of respondents reported their RT leaders held regular neighbourhood meetings, 53% reported receiving in-person visits and 54% said they keep in touch via Whatsapp chat groups.

Selective enforcement of Covid-19 measures by neighbourhood leaders

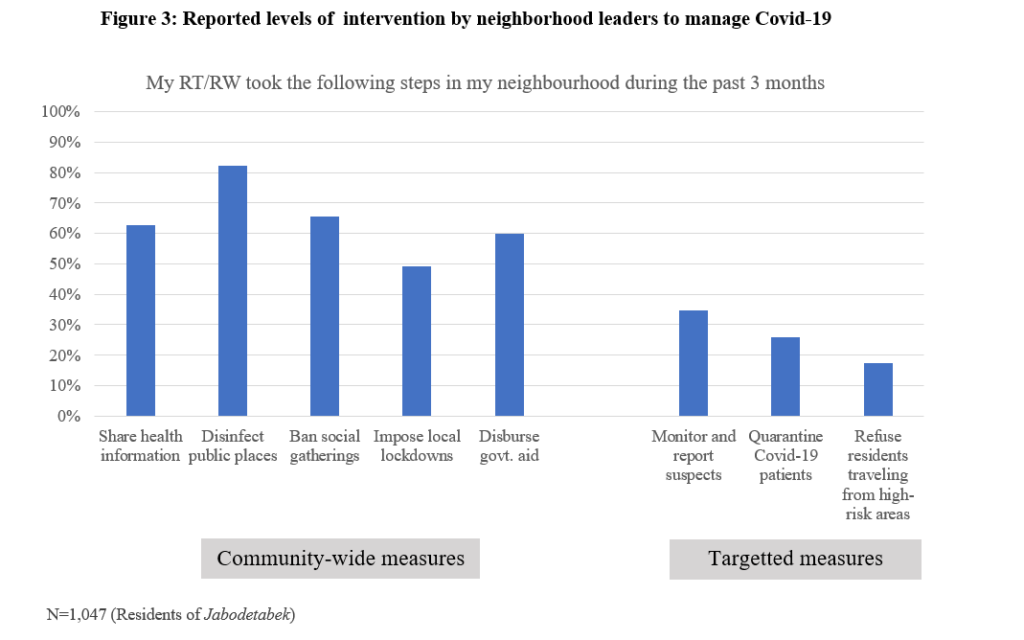

Despite high levels of resident support for making a wide range of COVID-19 related interventions, the data show that RT/RW leaders are highly selective in actually enforcing these measures (Figure 3). Over 60% of respondents reported that their RT/RW leaders had taken community-wide measures. These include non-restrictive measures, such as dissemination of health information, spraying of disinfectants and distribution of government aid, as well as fairly restrictive ones like prohibition of public gatherings in the neighbourhood. The enforcement of strict lockdowns by RT/RW leaders to limit movement of residents in and out of neighbourhoods is less common but still reported by almost 50% of respondents. Fewer than 4% of respondents said their RT/RW leaders had refused burial to patients or evicted their families.

Compared to community-wide measures, RT/RW leaders appear to have been much more reluctant to impose targeted restrictions on specific residents. Less than 35% respondents reported that their RT/RW leaders were reporting suspected patients to health authorities, imposing mandatory quarantine on them or restricting entry to residents returning from travel to high-risk areas.

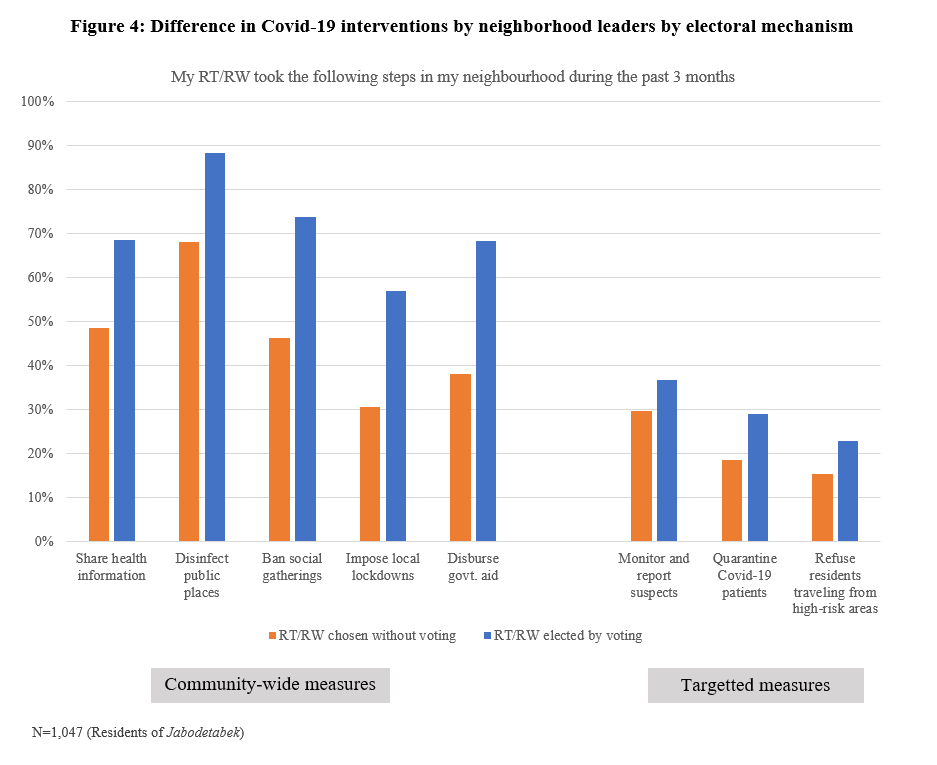

Enforcement of COVID-19 related measures also vary based on the mechanism through which RT/RW leaders were chosen. The data show that neighbourhood leaders who were reported as being elected through an open voting process were overall more likely to enforce COVID-19 related measures, compared to those who were elected through non-voting consensus or government appointment (Figure 4). The mechanism of choosing RT/RW leaders’ seems to be a bigger factor in increasing the enforcement of community-wide measures, but not in targeted measures.

What drives this variation across neighbourhoods? One possibility is that variation in the provision of operational funds by respective regional governments drives different rates of enforcement. If so, RT and RW leaders in Jakarta, who receive IDR 2 million (US$ 141) and IDR 2.5 (US$ 177) million a month respectively, would be more likely to enforce government mandated measures, compared to RT/RWs in surrounding satellite cities like Depok where they receive only IDR 200,000 (US$ 14) and IDR 300,000 (US$ 21) per month. However, the data show no significant difference in enforcement rates between Jakarta and its eight surrounding districts.

Instead, social and political factors seem to be at play. First, RT/RW leaders tend to be concerned about conflict with their residents, as maintaining the appearance of neutrality is critical for their ability to perform their daily tasks and keep their social standing. This could explain why RT/RW leaders are open to imposing collective restrictions but hesitant to single out residents for invasive measures. Disputes with individuals who feel badly treated could lead to accusations of personal animus, gossip and slander. In several cases, residents who have refused testing, quarantine or even treatment, have had to be evacuated by law-enforcement officers against their will. Being associated with forced government measures against specific residents can cause long-term reputation damage to RT/RW leaders and may deter enforcement of targeted interventions.

Second, leaders’ own perception of their political legitimacy may affect their ability to take invasive or contentious measures. This explains why the rate of government aid distribution and lockdown enforcement is twice as high in neighbourhoods where RT/RW leaders were elected by open voting rather than informal consensus or temporary appointment. Strict lockdowns that can affect residents’ economic and social life are likely to be unpopular, especially if they are imposed over an extended period of time. Similarly, distribution of government aid during the pandemic can be a contentious process within a neighbourhood due to limited availability of funds and a growing list of those who need assistance. The results suggest that RT/RW leaders elected through open voting feel more secure about taking unpopular measures for the collective good.

Without social safety nets, Indonesia risks political instability over COVID-19

Economic disasters have a history of bringing down governments in Indonesia; COVID-19 impacts hardest on the disadvantaged in an already fragile system.

Understanding constraints on neighbourhood authority for effective mobilization

As the Covid-19 pandemic rages on, governments around the world are exploring ways to limit contagion without bringing the economy to a standstill. Indonesia has the infrastructure to balance these concerns in the form of its vast network of neighbourhood organizations. Understanding both the strengths of neighbourhood authority as well as the social and political factors that limit its exercise is critical for their effective mobilization.

Preliminary results from the Jabodetabek survey show that RT/RW leaders’ greatest strength is the public’s trust and approval. However, the likelihood of translating this mandate into action, depends on neighbourhood leaders’ own perception of their legitimacy. Improving the transparency of election procedures for RT/RW leaders in the future may well improve their ability to support everyday governance.

The results presented here also suggest that while RT/RW leaders can assist in the implementation of official programs, they cannot substitute for the state. Unlike formal government officials, RT/RW leaders live in close proximity to the residents they govern and have thick social ties with them. As such, directives that require neighbourhood leaders to single out their neighbours are unlikely to be enforced broadly and might be better implemented by formal government agencies.

This research was funded by the National University of Singapore and was implemented in partnership with Katadata Insight Center.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss