Ask the average Indonesian voter what they believe it takes to be a winning legislative candidate and you’re likely get the response: “harus punya duit”—“[they] must have money.”

These voters’ intuitions are backed up by plenty of research showing that political campaigns in Indonesia are expensive—and that costs are on the rise. To stand a chance in any legislative election, would-be politicians must pay the salaries of sprawling campaign teams, purchase mountains of campaign paraphernalia, and hand out envelopes of cash to voters on election day. These costs can come to over US$50,000 for a candidate at the district or city level; for national parliament, political aspirants can spend upwards of US$2 million. Individual candidates, rather than their party, foot the bill, and failure to win office can lead to financial ruin. Given the obvious advantages that personal wealth affords a candidate in such a system, it is little surprise that businesspeople and oligarchs are entering politics in growing numbers.

All of these realities were on display in February 2024, when Indonesia held elections for city, district, province and national legislatures alongside its presidential ballot. Legislative candidates we’ve spoken to described the campaign as financially “brutal”, with the huge sums of money spent by tens of thousands of candidates prompting some to conclude that this year’s elections were the most expensive in Indonesia’s democratic history.

Given the spiralling costs of campaigning, it’s unsurprising that voters believe only the wealthy can run for office. But just how wealthy does one need to be to win a seat in parliament in Indonesia? And do some candidates need more money than others? So far, researchers haven’t had the kind of data that can systematically investigate the effect of legislative candidates’ personal wealth and campaign spending on their chances of electoral success. To fill this gap, we used the 2024 elections to conduct a unique survey of candidates that for the first time allows us to test the extent to which wealth begets representation in Indonesia’s local legislatures. We also explore the extent to which money offsets countervailing factors thought to hurt candidates’ chances of success. Do candidates who face “demographic headwinds”—for example, women—need more money to offset their electoral disadvantage? On the flip side, do some candidates need less money, like those with dynastic connections, who can use their name and networks for electoral gain?

The data

To explore these questions, we use the first panel survey of legislative candidates ever conducted in Indonesia. Starting in November 2023 we worked with Saiful Mujani Research and Consulting to survey a random sample of candidates running for seats in city (kota) and district (kabupaten) level legislatures (DPRD Tingkat II). Out of feasibility concerns, we imposed several restrictions on the pool of candidates, restricting our sample to candidates in the first three positions on their party lists, and who were running with parties that were polling above 1% as of 1 October 2023. We also excluded candidates running in Papua and Maluku over concerns about the costs associated with surveying respondents in hard-to-reach areas.

Our survey was a panel, meaning we attempted to survey the same 800 candidates three times: twice before the election, in November 2023 and January 2024, as well as once after the election, in April 2024. In the end, we obtained an 81% recontact rate, meaning approximately 650 candidates were surveyed in all three waves. We believe these data thus offer a uniquely fine-grained portrait of the evolving attitudes and behaviours of legislative candidates over the course of their campaigns.

The findings

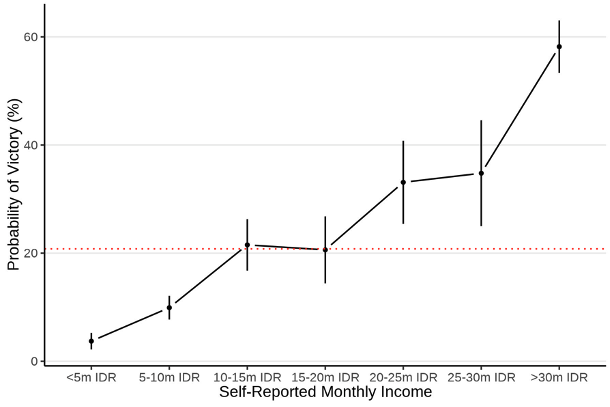

We establish several stylised facts about the relationship between wealth and representation in Indonesia, which characterise a larger phenomenon we intend to explore in a series of related articles using this new dataset. First, in Figure 1, we find a striking linear relationship between wealth and electoral success (the dotted red line represents the overall chance of victory, i.e., ~20%). The richer the candidate, the more likely they are to win a legislative seat. To put this finding in concrete terms: compared to the poorest candidates (those who earn less than Rp5 million per month), the richest candidates (those who earn more than Rp30 million per month) are more than fifteen times as likely to win their race.

Figure 1: relationship b/w candidate income and probability of victory

Because campaigns are chiefly self-funded at the local level in Indonesia, wealthy candidates spend more than their poorer peers. But what do wealthy candidates spend their money on to secure higher chances of victory?

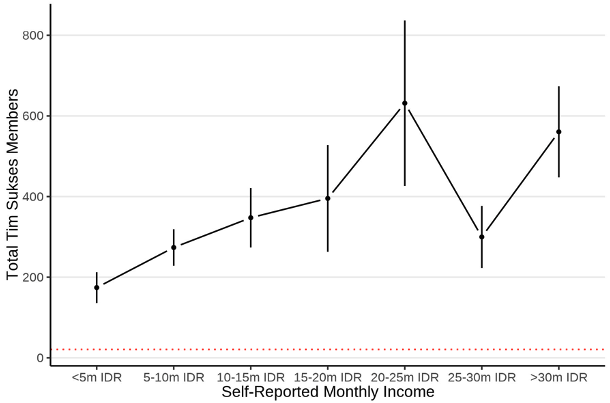

Our survey reveals no changes in the composition of their spending: wealthier local candidates continue to spend considerable sums of money on baliho (banners) and the purchase of votes. In other words, richer candidates are not more likely to adopt different and more sophisticated campaign strategies. Instead, what we unearth is evidence that richer candidates are simply able to build larger campaign teams (tim sukses). Figure 2 shows the size of candidates’ campaign teams according to their monthly income, showing that richer candidates are able to spawn patronage networks that are three times as large as their poorer challengers.

Figure 2: relationship b/w candidate income and campaign team size

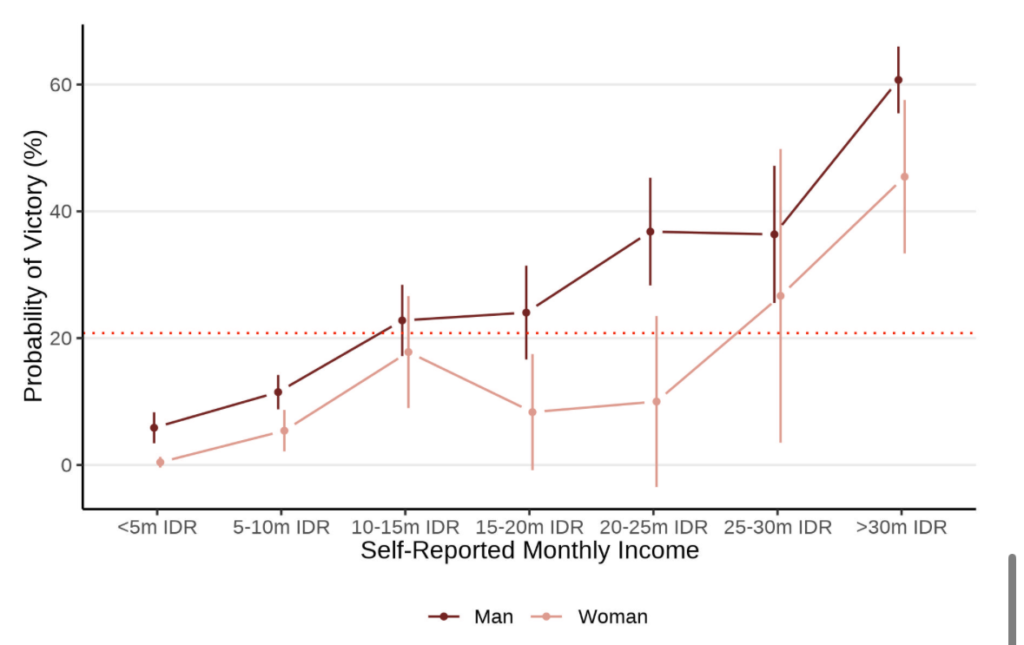

These findings will not come as a surprise to observers of Indonesian politics. Our principal interest in this project, however, is in understanding the extent to which money matters in Indonesian elections. On this count, the magnitude of our finding merits a second look. Money simply dwarfs other conventional predictors of success: in comparison, consider that men are only two and a half times more likely to win than women; those with tertiary degrees are three times as likely to win compared to those with only a high school diploma; and, the oldest candidates are only twice as likely to win as the youngest.

In short, the advantage enjoyed by wealthy candidates outstrips virtually every other feature thought to be predictive of electoral success. We explore these results in greater depth in Figures 3 and 4. Take gender, in Figure 3, for example. Rich men generally perform better than rich women. And men tend to be richer than women. But, rich women perform considerably better than poorer men. For instance, a woman who reports earning more than Rp30 million per month has a 42% chance of success, which is approximately eight times larger than the 5% chance of success reported by a man who earns less than Rp5 million per month.

Figure 3: relationship b/w candidate income and probability of victory, by gender

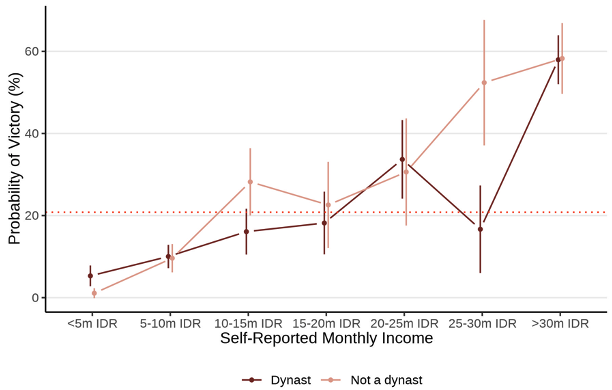

In Figure 4, we conduct an analogous analysis looking at a candidate’s status as a member of a political dynasty (or not). With Gibran Rakabuming Raka’s recent election as vice president on Prabowo Subianto’s ticket, analysts of Indonesian politics are rightly attuned to the influence of nepotism in structuring electoral politics. But Figure 4 reveals that one’s status as a dynast is in fact inconsequential when viewed in light of the electoral advantage of wealth. Indeed, it may be the case that dynasts and incumbents perform better simply because they are wealthier than their competitors—not because of any inherent advantage conferred by the political networks coming with those positions. Figure 5 shows, consistent with this, that wealthy dynasts have equivalent electoral prospects to wealthy non-dynasts—and that this relationship holds across the income distribution.

Figure 4–Relationship b/w Candidate Income and Probability of Victory, by Dynasty

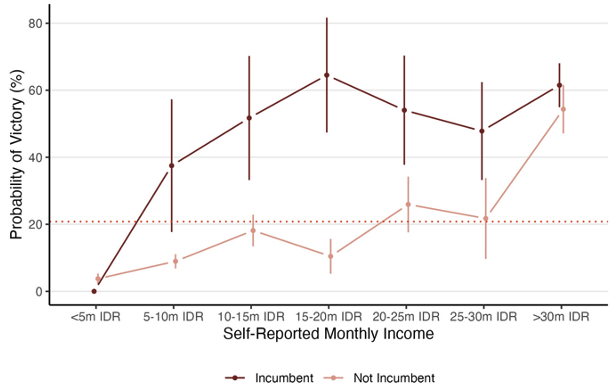

One exception to our findings concerns the role of incumbency. Figure 5 shows that, once in office, poorer candidates do approximately as well as their richer peers—although a slight electoral disadvantage continues to exist. To cite concrete numbers, 40% of incumbents who earn Rp10 million a month won their contests, compared to 60% of incumbents who earn more than Rp30 million a month.

The attenuated relationship between wealth and victory among incumbents likely derives from their ability to deploy state resources to their electoral advantage, rich or poor, once in office. Consistent with this interpretation, non-incumbents exhibit the same positive relationship between income and probability of victory. Though, once a non-incumbent candidate earns more than 30 million per month, their probability of winning the election is statistically indistinguishable from an incumbent’s.

Figure 5: relationship b/w candidate income and probability of victory, by incumbent status

Conclusion

The survey data paint a remarkably clear picture of the role that wealth plays in Indonesia’s legislative elections. We’ve known for some time that “money matters”. But the relationship we uncover here between income, spending, and electoral success is arguably more dramatic than existing studies have suggested. Of particular significance is how these data illustrate the advantage that wealth affords political candidates over and above other characteristics often assumed to play a determining role in electoral victory, such as dynastic connections. There is little doubt that entrenched patterns of clientelism and under-financed political parties have, over the last two decades, driven up the cost of politics and created barriers to entry for less wealthy candidates.

Analysts have a less firm grasp on precisely what it means for the quality of Indonesia’s democracy if the country’s representative institutions become accessible only to the very rich. On the one hand, some of the classic work on politicians’ backgrounds suggests class has little impact on the kinds of things they do in office—primarily in contexts where there is a strong programmatic party system such that politicians’ actions are constrained and shaped by party ideology and platform.On the other hand, in a political system like Indonesia’s, where programmatic politics are weak, class backgrounds potentially matter more for how politicians behave in office, what they prioritise, and what kind of policies they pursue. The data we present here suggest this is an important line of enquiry for future research, given there is little to indicate that rising political costs will reverse any time soon.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss