The story of the Batavia – characterised by a midnight shipwrecking, months of murder and mayhem under mutinous Under-merchant Jeronimus Cornelisz and his henchmen, and the heroic rescue of the remaining survivors – continues to fascinate both scholars and the public. Out of approximately 332 crew and passengers, only about 125 survived.

Now, Melbourne-based artist Melinda Piesse has re-visited this tragedy through the creation of a large-scale embroidered work known as the Batavia Tapestry. Having made its debut at the Australian Wooden Boat Festival in Hobart earlier this year, the Batavia Tapestry is now on display at the Australian National Maritime Museum’s Tasman Light Gallery until 29th October 2017. Piesse will give a public talk about the project in Sydney on 3rd August as part of the ANMM’s Member Maritime Series (bookings are essential via the ANMM website).

Melinda Piesse and her Batavia Tapestry, photographed by K. Kingston. Image: Melinda Piesse

It is fascinating to see Piesse’s use of cloth to narrate this story, not least because textiles played such a significant role in the story of the shipwrecked survivors. There are few trees on these islands, and the sun beats down relentlessly. In these harsh conditions, textiles provided essential shelter for the survivors. Sailcloth became a form of currency far more valuable than jewels and coins.

The bloodthirsty Cornelisz also used textiles as a way of empowering and distinguishing his small yet vicious group of followers. Those most willing to kill were gifted silk stockings and garters, gold and silver braids, and the finest lace and wool cloth of indigo and scarlet, from which they fashioned make-shift uniforms.

They were, literally, dressed to kill.

Low-lying shrubs provide little coverage on these islands. Image: Natali Pearson

Piesse’s Batavia Tapestry weaves together the utilitarian and the opulent. Taking the form of a traditional sailcloth, the enormous linen canvas (3 m x 5 m) is embellished with key scenes from the Batavia story – the ship’s wrecking on Morning Reef near Beacon Island, the horrors that followed, and their miraculous rescue three months later. As she told Signals Quarterly,

I chose to depict the key events of the Batavia before and after the ship’s wrecking: the attempts of the passengers to reach shore, first settlement, the mutineers’ plots to seize control, and the first open killing of a young boy (who had made the mistake of speaking to a mutineer’s mistress). Also depicted is the departure of the ship’s officers in a longboat, and their dramatic return amidst an epic battle and race to capture the rescue ship.

Key events from the Batavia story as shown on Melinda Piesse’s Batavia Tapestry. The third image depicts survivors on a raft, including a woman holding a baby. Photographed by K. Kingston. Image: Melinda Piesse

Piesse used custom-dyed wool felt to match yarn from the Australian Tapestry Workshop, and a combination of ancient techniques (including appliqué, crewel and gold work embroidery) to create the detail in her artwork. The deliberately-limited colour palette – olive, gold, madder, indigo and cochineal red – is reminiscent of the famed Bayeux Tapestry, and Piesse has expressed hopes that her tapestry will be seen as a modern day version of this medieval masterpiece.

A detail from the Bayeux Tapestry, held at the Reading Museum. Image: Wikimedia commons

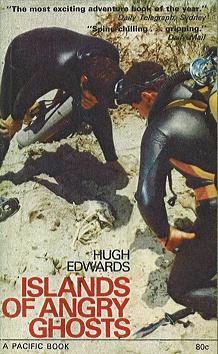

Piesse spent over three years researching and planning this work, and some seven years executing it. Proving that sometimes you can judge a book by its cover, Piesse was initially inspired by Hugh Edwards’ Islands of Angry Ghosts, which shows divers inspecting human remains in a shallow grave. Says Piesse, ‘I couldn’t imagine a more perfect exile, or a grander philosophical challenge, for a group of desperate people struggling for survival, so far away from civilisation, to endure the harsh conditions without falling into savagery.’ Rather than reducing it to questions of ‘savage’ and ‘civilised’, Cornelisz’s actions – organising gangs of thugs, instilling fear in the population, and rewarding the murderers with high status objects – could also be seen as indicative of the complex social organisation and hierarchy that developed quickly in the hothouse atmosphere of these remote islands.

Says Piesse, ‘I couldn’t imagine a more perfect exile, or a grander philosophical challenge, for a group of desperate people struggling for survival, so far away from civilisation, to endure the harsh conditions without falling into savagery.’ Rather than reducing it to questions of ‘savage’ and ‘civilised’, Cornelisz’s actions – organising gangs of thugs, instilling fear in the population, and rewarding the murderers with high status objects – could also be seen as indicative of the complex social organisation and hierarchy that developed quickly in the hothouse atmosphere of these remote islands.

Piesse conducted extensive research on the 17th century world, particularly the Dutch East Indies Company, which had invested in the construction and voyage of the Batavia. She immersed herself in old world maps, maritime paintings and archives to learn more about the ships that undertook these long-distance voyages, as well as the people they carried: explorers, soldiers, seafarers, mercenaries.

‘Ships in a stormy sea’ by Willem van de Velde. 1671-1672. Oil on canvas. H: 132.2 cm, W: 191.9 cm. Toledo Museum of Art.

Contemporary references included the Swedish warship Vasa, replicas of both the Batavia and the Batavia’s Longboat, and the Duyfken (‘Little Dove’).

The Swedish warship Vasa. Image: Scoobyfoo / Flickr

A replica of the Batavia was built at the Bataviawerf (Batavia Wharf) in Lelystad, the Netherlands, and was launched in 1995 under master-shipbuilder Willem Vos. Image: ADzee via Wikimedia.

The Duyfken on her historic voyage in 2016 to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Dirk Hartog’s landing on the Western Australian coast. Image: R. Polden

As a representation of a historical sail, the Batavia Tapestry shows evidence of Piesse’s extensive knowledge of ship’s rigging and rope work. It is finished like an authentic 17th century top-gallant sail edged with tarred marline and hemp rope, and is displayed upon a wooden spar constructed by master shipwright (and Piesse’s husband) Wayne Parr.

Melinda Piesse and her Batavia Tapestry, photographed by K. Kingston. Image: Melinda Piesse

Much of Piesse’s technical knowledge comes from her time volunteering onboard Melbourne’s tall ship Enterprize, where she became intrigued with the chief sailmaker’s use of traditional materials such as authentic flax sailcloth and hemp rope from Holland:

They’d stir these big bubbling pots of Stockholm tar, thick and black as licorice, and paint the standing rigging to repel the water. It was an amazing process and I started to experiment artistically with some of their traditional techniques.

A detail from the Batavia Tapestry, showing Piesse’s fine embroidery and detailed ropework. Image: Natali Pearson

As is common with many re-tellings of the Batavia story, one perspective that the Batavia Tapestry does not shed new light on is the final destination of the ship – the Dutch East Indies.

Although Piesse’s stunning creation has much to offer both artists and maritime historians, those interested in Southeast Asian pasts will be left with questions about the ship’s intended destination, and about the implications of its failed voyage. What impact did its sinking have on the Dutch colony, if any? What happened to those who did finally make it to Java? And what can this event tell us about the historical connections between the Netherlands, Australia and Indonesia?

Even as this story is told and re-told, there are many alternative perspectives still to be explored.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss