For almost four years, the government of Joko Widodo (Jokowi) has been steadily ramping up its efforts to roll back Islamist influence within Indonesia’s political system and society. Although the anti-Islamist campaign has not been formally declared or been given a name, it has nonetheless been systematic and concerted. It has included the investigation and prosecution of leading Islamist leaders, restrictions upon Islamists within the public service, closure of websites and social media pages, and the proscription of Islamist organisations.

The boldest move in this campaign took place in the last days of 2020, when the Jokowi government announced the banning of the Islamic Defenders’ Front (Front Pembela Islam or FPI). FPI was by far the largest and best-known Islamist organisation to be so targeted – it claimed a membership of seven million, had branches in every province and broad networks across the Muslim community. The ban was the culmination of two months of sharpening confrontation between the government and FPI and its fiery spiritual leader, Habib Rizieq Syihab, who had returned to Indonesia in November 2020 from three years’ virtual exile in Saudi Arabia. He drew large crowds wherever he spoke. Six FPI guards were shot by police in early November in a clash between Rizieq’s security detail and a police surveillance team, and a week later Rizieq was arrested and put on trial – he was found guilty in late May on one charge of breaching public health protocols and jailed for eight months. Six other senior FPI leaders were also jailed for the same offence. (All are likely to be released in the next month or so due to time already served in detention.)

This showdown between the government and Islamist groups is not without political and security risk. Jokowi has been vulnerable to Islamist criticism and mobilisation in the past and he and his governing coalition appear determined to drive organisations and movements such as FPI to the margins of national life. If the Muslim community comes to see the FPI ban as anti-Islam (rather than just anti-Islamist), the government could suffer a backlash. There is also the possibility of former FPI members and sympathisers becoming further radicalised and more violent as a result of the state’s action.

In this article, we examine the public’s reaction to the crackdown using data from a Lembaga Survei Indonesia (LSI) survey from mid-April commissioned by ANU as part of a research project into religious polarisation in Indonesia, but other data from the Saiful Mujani Research Consultancy (SMRC) will also be used.

A clear majority of the public approves of the government’s actions in banning FPI. Moreover, community dislike of FPI and of several other Islamist groups has strengthened over the past year, suggesting that the government is winning the politics of its battle with Islamism, at least in the short term. More broadly, we will argue that the limited opposition to FPI’s proscription is indicative of shrinking political support for Islamism over the past five years and an endorsement of government efforts to sideline Islamists. We will explore where FPI’s basis of support lies and the reasons for the apparent ebb in public sympathy.

FPI’s Vigilante Islamism

Since its formation in 1998, FPI’s central feature was its ability to mobilise on the streets and take direct action against those who it saw as acting contrary to Islamic principles. Vigilante attacks on nightclubs, brothels, gambling dens and so-called ‘deviant’ Islamic groups such as Ahmadiyah or the Shia were common, as also was the intimidation of and sometimes serious assaults upon liberal-minded Muslims, non-Muslims and even social-media critics of FPI. Scores of FPI members have been arrested and jailed for violence and Rizieq himself was twice jailed in the 2000s. Despite its thuggish behaviour, FPI has often been courted by prominent political and business figures, and even used on occasions by the police and security agencies to ‘maintain’ law and order.

FPI’s influence reached its highpoint in 2016-2017 when it played a pivotal role in mobilising 100,000s of Muslims in Jakarta against the Christian Chinese governor, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (‘Ahok’), ultimately resulting in his defeat in the ensuing gubernatorial election. The massive protests shook the Jokowi government, giving rise to fears that Islamists, after many decades of fragmentation and peripheral activism, were now in a position to shape national politics. Soon after the Jakarta elections, the government began moving against its Islamist opponents. Many Islamists came under investigation: some were jailed while others quietly removed themselves from public view. Rizieq himself went off to Saudi Arabia in April 2017 to escape prosecution on multiple charges. The Islamist organisation, Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia, was banned by the government in July 2017.

The government gave four reasons for outlawing FPI on 31 December last year: it had forfeited its legal status after its registration as a community organisation had lapsed; some of its members had been involved in terrorism and other criminal activity; it had often committed acts of communal vigilantism; and it had violated the principles of the 1945 Constitution, the state ideology Pancasila and the Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia. The government followed up with a range of other measures, including freezing all FPI’s bank accounts, closing its social media sites, and warning the media not to publish any information from FPI sources. The public’s reaction to the banning and the government’s explanations is worth exploring further

Public Responses

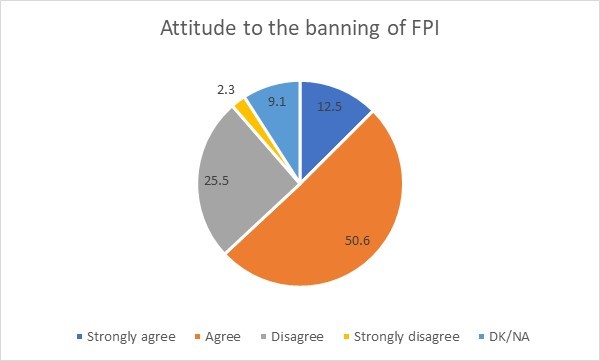

The April 2021 LSI survey involved 1620 respondents across all provinces of Indonesia. When asked if they were aware of FPI’s banning, a surprisingly high 48% said they did not know, even though news of this and related matters had dominated the media for months. Of the 52% who were aware of the ban, 63% approved and 28% were against [see figure one]. By comparison, a February 2021 national survey by SMRC found that 77% of respondents were aware of the ban. Of those, 59% agreed with the ban and 35% disagreed. This suggests that roughly twice as many people approve of the ban as disapprove of it, and that over the past few months, opinion in favour of the government’s actions has strengthened.

Figure One: Attitude to the banning of FPI (April 2021 LSI Survey)

A breakdown of the figures gives a clearer picture of where FPI’s support lies. Of Indonesia’s ethnic groups, the Buginese, based mainly in South Sulawesi, and the Sundanese concentrated in West Java were the most disapproving of the ban (66% and 43% respectively). The Betawi community in the Greater Jakarta region, which has been a major source of FPI recruitment, was unexpectedly evenly divided on the ban, with 45% agreeing with it and 41% disagreeing. Those with higher education levels were most likely to know about the ban (75%) as well as disapprove of it (32%). Also surprising was that some 75% of under-25-year-old respondents favoured the ban.

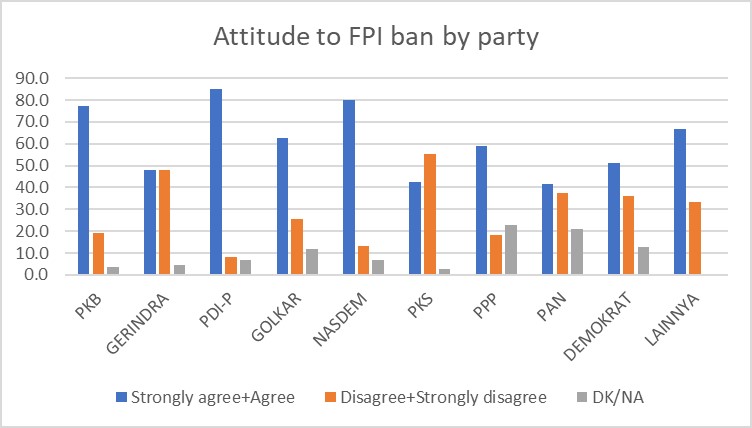

The Prosperous Justice Party (PKS) was the only Islamic party that had a majority of its supporters opposing the ban (55%), with 29% endorsing it. This reflects the close ties that developed between PKS and FPI during the anti-Ahok demonstrations and the 2019 election campaigns. Opinion among supporters of the three other Islamic parties was pro-banning: the National Mandate Party (PAN) supporters were 42% in favour, 37% against; the United Development Party (PPP) was 59% in favour, 18% against; and the National Awakening Party (PKB) was 77% in agreement and only 19% against [see figure two]. More broadly, 59% of Muslim respondents backed the ban (31% were opposed), whereas 97% of non-Muslims favoured it – a predictable outcome given FPI’s long sectarian agitation against religious minorities.

Figure Two: Attitude to the banning of FPI ban by party, with party affiliation on basis of voting in 2019 legislative election (April 2021 LSI Survey)

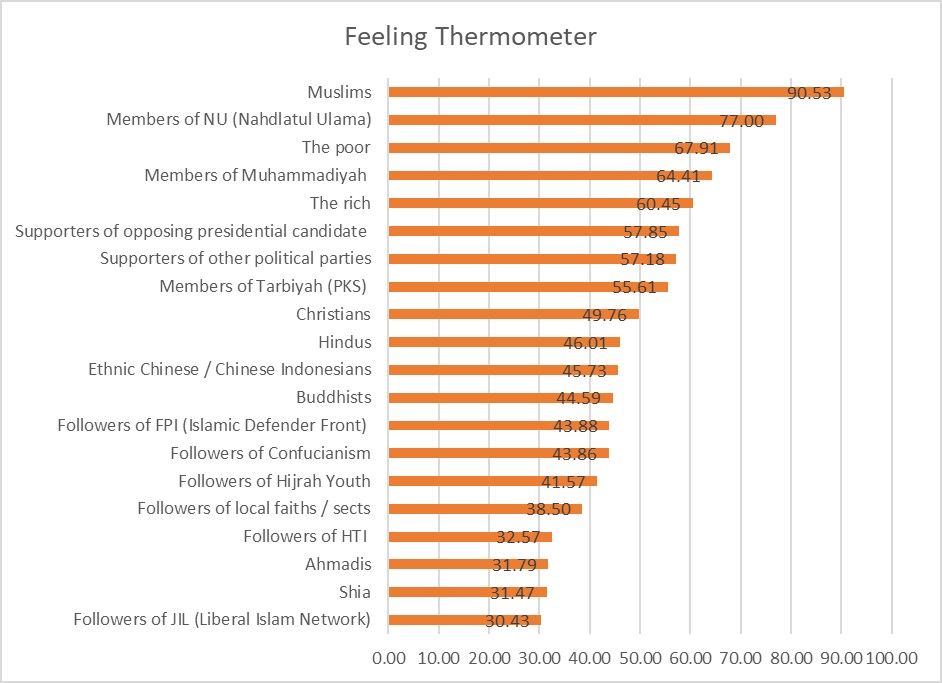

Perhaps even more revealing of the equivocation felt in the Muslim community towards FPI was the results of “thermometer” questions in which respondents were asked how warmly or coolly they feel towards an array of religious and political organisations. [see figure three] Whereas the major Islamic organisations rated highly—Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) 77% and Muhammadiyah 64%—FPI was ranked in the “cool” lower half of the thermometer on 44%. Notably, respondents felt more warmly towards the Chinese (46%) than to FPI, which was ironic given FPI’s frequent disparagement of the Chinese community. A related question about which groups respondents objected to having as neighbours found FPI the sixth most unpopular at 24%, comparing unfavourably with supposedly ‘disliked’ minorities such as the Chinese and Christians (both 18%).

Figure Three: Feeling thermometer asking respondents how warmly they feel towards a range of religious groups (April 2021 LSI Survey)

A glance at historical survey data shows that FPI’s profile and public approval has fluctuated widely since its formation in 1998. An LSI survey for The Asia Foundation in 2010 found that approval of FPI was 15% in 2005, 20% in 2006, 13% in 2007 and 16% in 2010.

Respondents in the April 2021 LSI survey were asked retrospectively what they thought of FPI’s actions in 2016 when it was the vanguard of the 212 movement: 46% said they agreed with its attitude towards Ahok; 36% disagreed. Support was strongest among young people, with highest levels of support coming in the 22-25-year bracket (54.4%), and then the under-21s (53.1%). The April 2021 figures show under-21s continue to be the strongest supporters of FPI, with 37.1% disapproving of the ban, but 22-25-year-olds were now those most in favour of the ban, with a massive 75% approval rating for the measure, compared to the average of 28% across all age groups. So, by far the biggest drop in support for FPI has been among young adults.

Interestingly, those with a university education were most likely to say that they disapproved of the FPI’s actions in 2016 (48% of respondents compared to 34% overall). But this same group were also most likely to disagree with the ban on FPI (32.5%). Given that this is a reversal of the general trend of decline in support for FPI, it is likely that this opposition to the banning of FPI is driven not by greater support for FPI, but by disapproval of the government’s actions. There are certainly some high-profile Muslim and civil society leaders who have spoken out strongly against the ban, arguing either that it is legally questionable or is an excessively repressive way to deal with militant Islamists.

Between throwing rocks and a hard place: FPI and the Jakarta riots

Clouds are gathering for the hard-line Islamic group.

The dramatic shift in public opinion, and especially Muslim attitudes, towards FPI over the past five years appears due to a number of factors. In 2016, FPI successfully exploited community anger towards Ahok, particularly relating to his supposed blasphemy against Islam, and portrayed itself as protecting the dignity of the faith against denigration by a prominent non-Muslim. But with Ahok’s 2017 defeat and subsequent jailing, much of the emotion dissipated from this issue, and along with it, approbation for FPI. Rizieq’s relocation to Saudi Arabia in 2017 left a vacuum in FPI’s leadership and a drop in its activities.

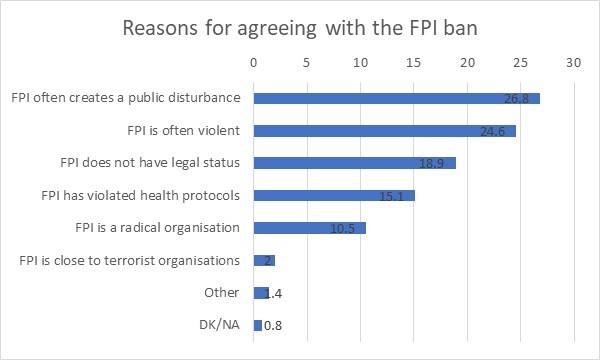

The fall in support for FPI this year appears heavily influenced by the organisation’s flouting of public health protocols in connection with Rizieq’s return to Indonesia in November 2020. Despite strict provisions regarding social distancing, hand sanitation and mask wearing, massive crowds greeted Rizieq when he arrived in Jakarta, paralysing the airport and causing traffic chaos in the city for much of the day. A few days later, thousands thronged to witness his daughter’s wedding ceremony and hear his sermon marking the Prophet Muhammad’s birthday. An SMRC survey in late November 2020 found that almost half their respondents knew of the airport and wedding crowds and, of those, 77% felt that law enforcement and the Jakarta government should halt such events and disperse attendees. The April 2021 LSI survey asked those who agreed with the ban why they did so: 25% said it was because FPI caused social disturbance; 24% mentioned its violent behaviour; 19% said it was an illegal organisation; and 15% said it had breached public health codes. (see figure four) Interestingly, only 10% regarded FPI as a radical organisation and a meagre 2% felt it was terrorist. These latter two points are significant because the government has used FPI’s alleged radicalisation as grounds for proscription, suggesting that the public is sceptical.

Figure Four: Reasons for agreeing with the banning of FPI among respondents aware of the ban (April 2021 LSI Survey)

All of this survey data points to a certain fragility in FPI’s support. FPI does have a solid constituency of at least around 15%, based on historical survey data. On occasions when FPI is able to capture and amplify anger or anxiety in the broader community on an issue, such as that of blasphemy during the 2016-2017 Jakarta election, its approval can spike. But at other times, its propensity for virulent rhetoric, intimidation and violence leads to public disapproval and censure. Over the past six months, its flouting of public health restrictions has further shrunk goodwill towards it.

The Jokowi government was undoubtedly aware of survey results on FPI prior to outlawing it—Coordinating Minister for Politics, Security and Law, Mahfud MD, cited polling as indicating public support when the ban was announced. The April LSI survey data presented here will no doubt further convince the government that its strike against FPI has been a resounding political success. It has effectively removed its most potent Islamist opponent and won public plaudits for doing so. Other Islamist groups are now wary of crossing the government, lest they also become targets. Rizieq, one of the government’s most vexatious critics, is in jail with a tarnished reputation. Many advocates of religious tolerance and pluralism will, perhaps paradoxically given their usual concern with democratic rights, also welcome the demise of such a provocative and militant group.

But the longer-term consequences of banning of FPI may be a greater cause for concern. Many millions of Islamists remain convinced of the correctness of FPI’s actions, as is evident from roughly 30% of survey respondents who think it was unjustly dealt with. Many in this group are likely to see the Jokowi government and indeed the Indonesian state as increasingly hostile towards them. The risk of growing resentment and extremism is high, as also is the possibility of political retribution should a more Islamically inclined president come to office in a future election with Islamist support.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss