Indonesia’s 2019 presidential election is currently operating under a peculiar paradox. On the one hand, there seems little to distinguish the presidential candidates on policy platforms. Opposition candidate Prabowo Subianto has been reluctant to criticise President Joko Widodo (Jokowi), and has run a timid and low-key campaign. Most Indonesians have found the televised debates boring. Local and foreign journalists claim there’s nothing particularly interesting going on. Presidential and vice-presidential candidates are not entering into clear contestation around the future direction of the country. In fact, the most prominent campaign material so far has been a “fake” account which encourages citizens to golput, or abstain from voting, apparently because the current options are so unpalatably similar.

On the other hand, many Indonesians describe the current political climate as deeply polarised. Vice-presidential candidate Sandiaga Uno recently declared that “we need to unite the country…this great disconnect hopefully after this election could be amended”. The General Elections Commission (KPU) declared it would form a “Peace Committee” for the third televised debate. One university invited me to give a guest lecture but asked me not to talk about the current election because it is a “sensitive topic”; a lecturer told me that the current discourse of politics is “bad for Indonesia and cannot be controlled”, where students “cannot agree to disagree”. At my lecture, one student asked me my advice for how Indonesia could achieve “peace” in its troublesome current political situation.

What drives this stark disconnect between the largely tame election campaign and the way many people feel about it? One way to answer this is to think about how online lives are distorting offline realities. Rather than Indonesia having a “polarising” election campaign, perhaps social media discourse is making Indonesians perceive that polarisation is potentially greater than it really is—and politicians are encouraging that perception.

Recent polarising campaigns

Of course, the previous two major elections in Indonesia could be defined as highly polarising, and in both cases social media discourse drove division. In 2014 Jokowi and Prabowo led a highly charged campaign in which the two were often portrayed in campaign material and in the media as starkly different. Jokowi supporters changed their Facebook page to “I stand on the right side” to support Jokowi. Many saw the “right side” as corruption-free meritocratic leadership, given that Jokowi had worked his way from local mayor to government of Jakarta to presidential candidate, as opposed to Prabowo who is a former military general and New Order figure, who spoke of family ties as key to his leadership credentials. The 2014 campaign caused serious friction in many family and marital relationships.

In one example of defining the polarising election, The Jakarta Post ran an editorial endorsing Jokowi because: “there is no such thing as being neutral when the stakes are so high… Rarely in an election has the choice been so definitive”. The Post argued that Jokowi was “determined to reject the collusion of power and business”, while Prabowo was “embedded in a New Order-style of transactional politics that betrays the spirit of reformasi”. Many human rights activists saw Jokowi’s defeat of Prabowo as a victory for democracy over authoritarianism. Jokowi may have disappointed these activists (and many others) in his first term, but the polarising campaign messages were clear in 2014.

Then came the undoubtedly polarising Jakarta election of 2017, where official and unofficial campaign material promoted Islam as focal point of the campaign and where we saw a rejuvenation of the term pribumi. Digital media was an increasingly important space for Indonesians to debate and discuss these issues, in private WhatsApp conversations, and more publicly on Facebook and Twitter. The media scholar Merlyna Lim described the 2017 social media election discourse as the “freedom to hate”. Add to that the rise of hoax news, “black” campaigning and paid trolls or “buzzers”, and Indonesian politicians, political parties and supporter organisations helped create a highly aggressive discourse in the digital public sphere. Middle-class Indonesians recall incredulously how in family or work WhatsApp groups someone disagreed with someone else and (gasp) left the group! Others explained about how you could not openly talk about who you would vote for because it would lead to segregation in religious communities.

Thus, Indonesians have just survived two polarising elections where debates were fervent and emotive, particularly online and on social media. As 2019 came around, it is of no surprise that many were both wary and weary of another election. As Prabowo once said: “democracy makes us tired”. But is Indonesian democracy currently having a power nap before the campaign begins in earnest, or is it sleep-walking into something completely different?

Social media and polarisation in 2019

In this election both Prabowo and Jokowi have clearly had “buzzer” teams working on shaping online discourse, as well as countering—and even creating—”black campaign” material. The language of war is often when describing the digital public sphere—Indonesia is said to be seeing a “weaponisation” of “online armies” and “cyber warriors”. Perhaps it is no surprise, then, that some Indonesians describe the situation as a “hoax emergency”. Most notable was Jokowi’s comment about Russian-style propaganda: “They don’t care whether it would cause divisiveness in society, whether it would disturb peace, whether it would worry the public,” he said, describing the propaganda as a systematic drive to “produce non-stop slander, lies and hoaxes that confuse the people”.

Citing some extraordinary cases, local experts have warned that that social media can easily cause conflict, because of low literacy levels. In the words of Indonesian academic Adi Prayitno, “many Indonesians are still irrational and tend to be emotional when it comes to different opinions in politics,” leading them to think politics is a “one way to heaven issue or a fight between good and evil”. The social media discourse in Indonesia colloquially describes Jokowi’s online supporters as “tadpoles” (cebong) and Prabowo’s online followers as “bats” (kampret).

At the heart of the idea of social media polarisation is comparing Indonesia to the United States. Foreigners are usually quick to assess that Indonesians are not particularly informed about world affairs, but it’s clear the US election is in the minds of many elites. In a recent speech, Agus Yudhoyono said the political divisions were caused by rampant misinformation and hoaxes on social media. “If this situation continues” he decried, “it will put an end to the country’s multiparty system and will lead the country to a two-party system like in the United States”, he said, adding that a duel party system was not suitable for Indonesia’s history and diverse society. National Police deputy chief Ari Dono Sukmanto agreed, saying recently that “[The disruptive effect of misinformation] happened in the [2016] presidential election in the United States. Perhaps this could happen to us, too”. One political campaigner on the Jokowi side told me the US election was crucial to their response to “black campaign” material: “Michele Obama said ‘when they go low, we go high’. But it didn’t work. Trump won. So here, when they go low, we go lower.”

Polarisation over what?

Despite all the concerns about division, disinformation and hoax news, the polls haven’t changed. Jokowi still leads around 57% to Prabowo’s 32%, and so far nothing has been created online or on social media to change those polls in any significant way. Rather than creating a “hoax emergency”, it seems the two online armies are largely fighting each other, while younger Indonesians increasingly move away from tense political discourse on Twitter and Facebook and turn towards the more apolitical platform of Instagram. “The Nurhaldi-Aldo golput phenomenon isn’t because people want a better candidate” my Indonesian colleague tells me. “It’s because people don’t want a contest. They’d rather joke about politics on social media than get into serious debates about it.”

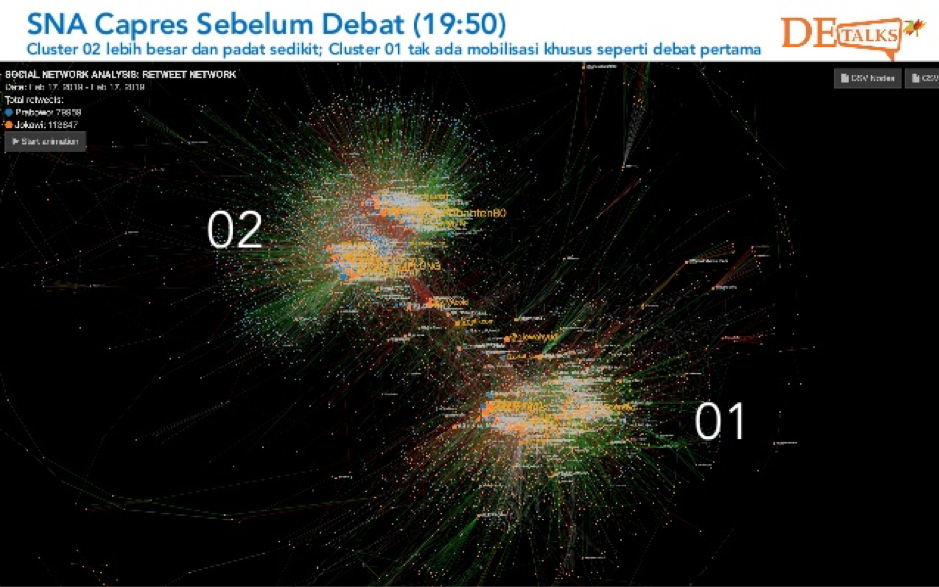

Shown below is a slide from Ismail Fahmi’s social media analytics company, Drone Emprit, which shows the “polarisation” of supporters that occurred on Twitter during the second televised debate. The “01” cluster represents Jokowi supporters and the “02” Prabowo’s. I would interpret this data as showing that the polarised online discourse is created largely by partisan buzzer teams.

But rather than acknowledging this, Indonesian politicians are more likely to argue that these partisan discussions online are the result of the election itself and the way Indonesians are engaging with politics, while in fact most Indonesians have found the debates procedural and boring.

Reducing contestation in 2019

The atmosphere of disinformation and division is having an effect, however, on how Indonesian elites and ordinary citizens feel about democracy. Direct and open contestation, a key feature of any democracy, is clearly a problem for many Indonesian politicians and even some of the public.

Yet despite the re-match of presidential candidates from 5 years ago, there is no clear ideological contestation in the 2019 election. The 2014 contestation of Jokowi as democrat versus Prabowo as New Order figure no longer fits. Jokowi is no longer the face of a reformist democrat, as Tom Power has argued at New Mandala. Furthermore, Jokowi has built consensus and is increasingly strict on opposing voices. He has managed to get the majority of political parties on his side, has most mainstream media companies supporting him (including those who were critical of him in 2014), and has pursued a more aggressive agenda to crack down on opposition figures through the Electronic Transactions Law (UU ITE).

Mapping the Indonesian political spectrum

A new survey shows that political parties are divided only by their attitudes on Islam.

But I’m not sure one can even distinguish Prabowo and Jokowi on these conservatisms anymore. As Jokowi has shown by appointing Maruf Amin as his running mate (and in many other facets of Jokowi’s politics), consensus is preferred to incorporating opposition forces rather than making a stand against them. Ridwan Kamil, who made a similar choice for vice-governor in his West Java election, described this process to me in this way: “In Indonesia perception about politics is always divided in Islamic image and nationalist image. So if the combination comes from both, people consider it as a balance. People consider me more as nationalist, which means I have to find a vice-candidate that has an image which is more from Islam.”

Those from Prabowo’s Gerindra party I have spoken to, meanwhile, has privately said that everyone would be invited to join their coalition should they win. Their most popular social media hashtag so far—simply #gantipresiden (“change the president”) —further encapsulating the ideological drought of the opposing camp.

The social media feedback loop

So social media is creating an artificial atmosphere of polarisation, which in turn gives politicians the excuse to avoid having serious policy or ideological contestations in the name of avoiding adding to that supposed polarisation. Perhaps scarred by the previous elections of 2014 and 2017, many politicians and Indonesian citizens are quite happy to see a stable—even boring—election where the incumbent president is re-elected easily. But if using contested social media discourse is clearly a way for politicians to reduce opposition and limit direct contestation, things aren’t so great either.

Of course, there is still a month to go and presumably we likely to see a highly contested election in 2024. But so far in this campaign, we are seeing an election missing something essential to a democracy—presidential candidates pitching clear ideological and policy differences.

It seems the emergence of social media disinformation and hoax news has meant many Indonesian politicians and citizens fear that the biggest threat to Indonesian democracy is, ironically, a highly contested election campaign.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss