Putting together a 400-piece, 3D puzzle is hard enough without the pieces warping and shrinking. But that was exactly the problem faced by maritime historian Horst Liebner and his team of expert Makassan boat-builders in Belgium last month when (re-)assembling a life-sized, traditional Indonesian sailing ship known as a padewakang.

The timbers had fitted perfectly when it was first constructed in the village of Tana Beru, South Sulawesi, earlier this year.

Ship-builders at work in Tana Beru, South Sulawesi. Image: Horst Liebner

But the long voyage from Indonesia to Belgium – not on water (as ships are designed to travel) but disassembled, wrapped in plastic, packed into a cargo plane and subjected to pressurized cabin air – had caused the wood to shrink and distort. Upon arrival in Belgium, low humidity had sucked even more moisture out of the planks and frames. The warped puzzle was a carpenter’s nightmare.

Each piece of timber was wrapped in plastic and transported to Belgium. Image: Horst Liebner

It’s not as if Liebner and his team faced the proposition of setting sail in a leaky boat. Their objective was, arguably, even worse: the padewakang had to be finished in time for an exhibition opening.

Despite these challenges, the padewakang was ready just in time for Les Royaumes de la mer (Kingdoms of the Sea), which opened at La Boverie museum in Liege, Belgium on 25 October 2017. This exhibition, curated by Intan Mardiana, is one of over 200 cultural events to be shown at the Europalia 2017 Arts Festival. As we wrote on the blog recently, Indonesia is the guest of honour for this year’s festival, and many of the exhibitions and performances relate directly to maritime aspects of this archipelagic nation.

The finished padewakang on display at La Boverie. Image: Muhammad Ridwan Alimuddin

Les Royaumes de la mer is based around the idea of the sea as connective rather than a barrier. In addition to the padewakang, the exhibition features nearly 250 objects from the National Museum of Indonesia, some of which have left the country for the first time. Also on display are rarely seen works from the Musée Royal de Mariemont and the Musée national de la Marine in Paris, as well as from private collections. For an insider’s view into the exhibition, including an interview with the curator, take a look at this short video.

Although the padewakang is a star attraction at Les Royaumes de la mer, it was not intended to be a polished museum piece. Instead, it’s a real ship, just as any of its kind from Tana Beru or the handful of other boat-building villages in the Makassan heartland of South Sulawesi.

Tana Beru and a handful of other villages in South Sulawesi are famed for their boat-building practices. Image: Wikicommons.

Tana Beru is home to master shipwright Haji Jafar who, though retired, oversaw the ship’s construction. He has passed his skills and knowledge on to his sons and grandsons, a number of whom (together with one of his daughters) travelled to Belgium to re-assemble the ship.

Haji Jafar (centre) with some of his family members at home in Bulukumba. Image: Horst Liebner / La Boverie

The finished vessel is nearly 14 metres long, three metres wide and, from keel to her lofty aft deck, over two metres high. Add the masts and sails and she near-fills the exhibition room from floor to ceiling. Not a single metal nail or screw holds the ship together – it’s all wooden dowels and fittings.

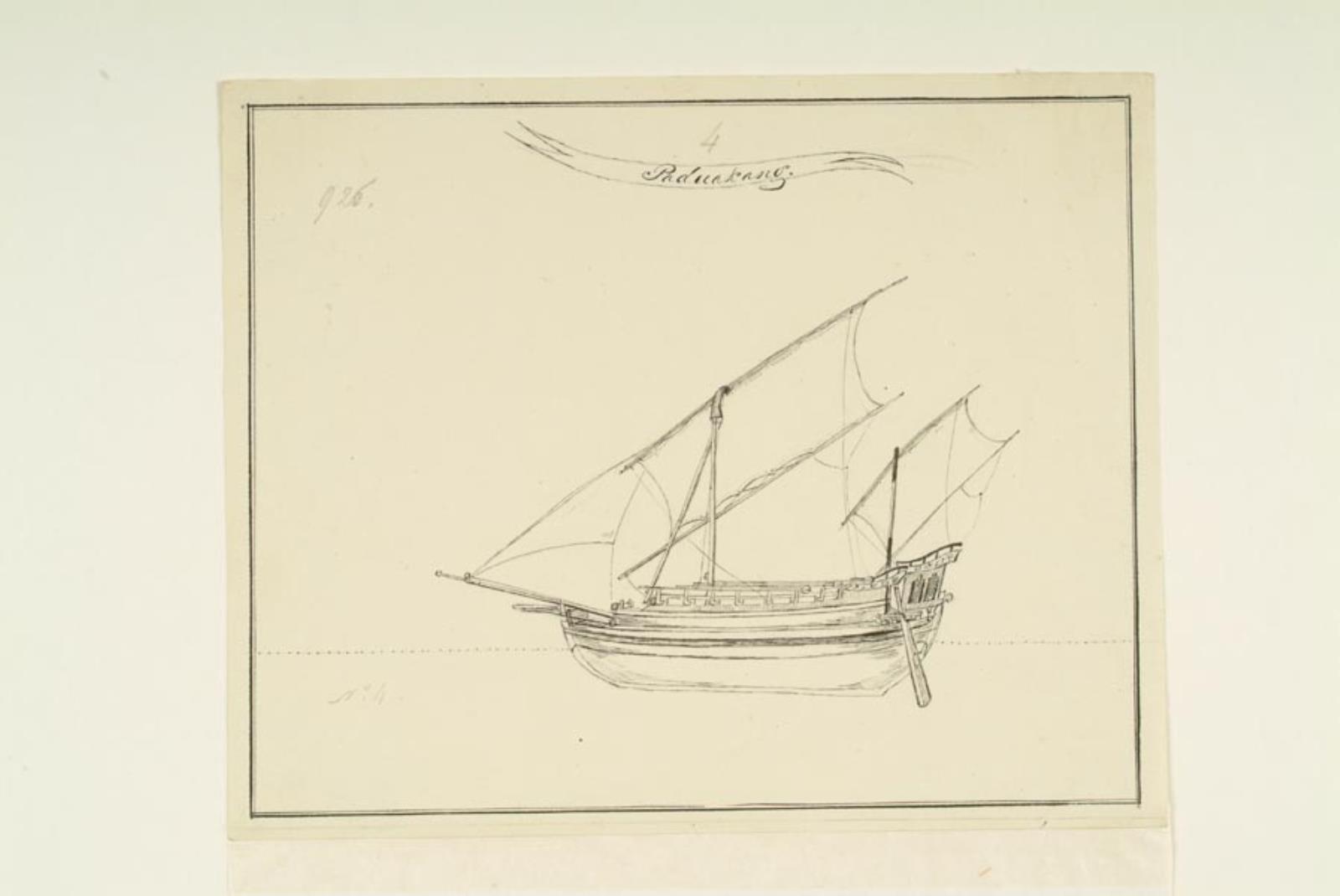

With an estimated capacity of 10 to 12 metric tons, the size of the vessel approximates smaller padewakang mentioned in Dutch harbourmaster records of the 18th century, and is also similar to vessels recorded on the north coast of Australia in the 1800s gathering trepang (edible sea slugs), mother of pearl and turtle shells.

Drawing of a ‘paduakang’, c. 1821-1828. Image: Maritiem Digitaal

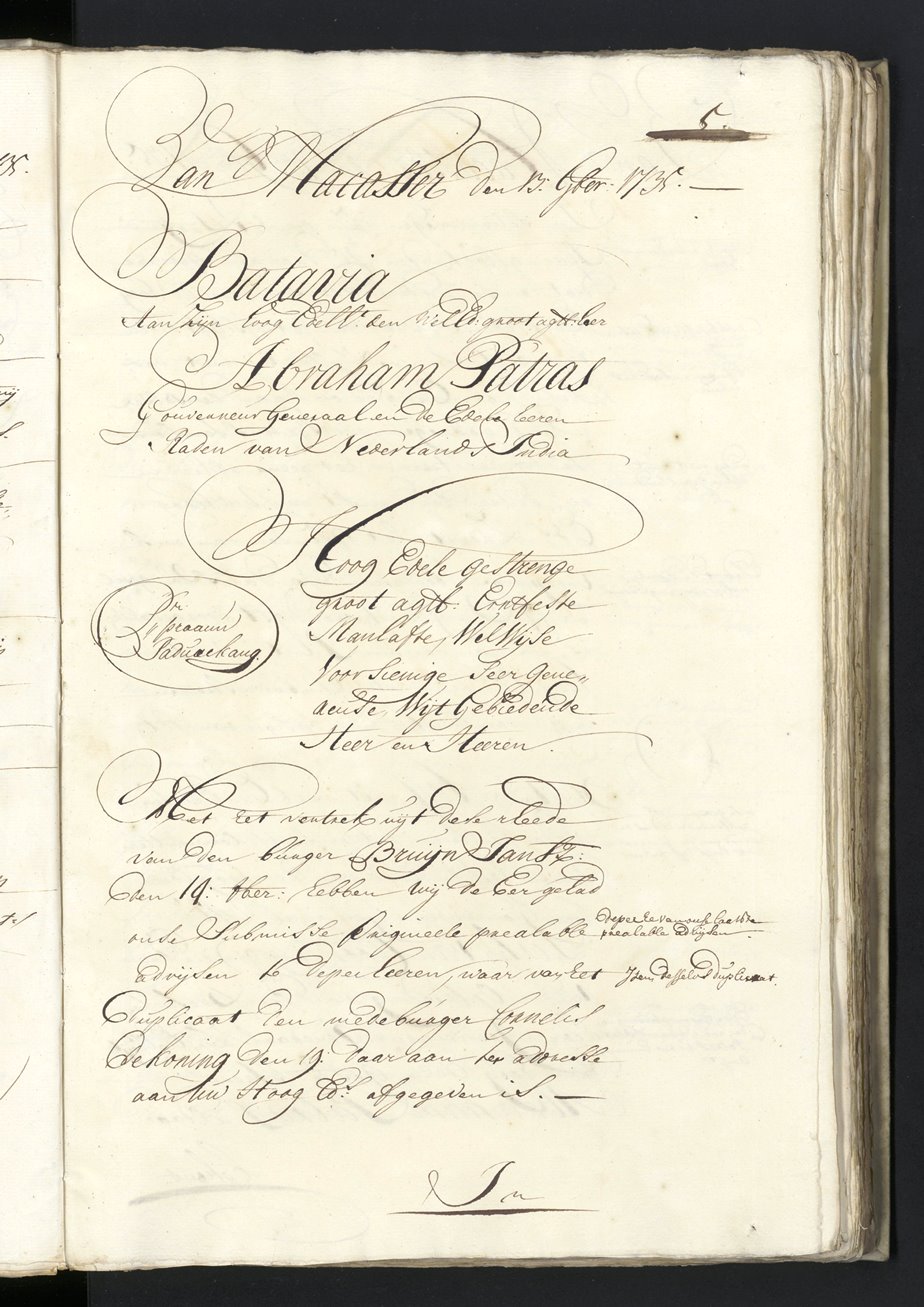

No-one quite seems to know the origin of the name padewakang, though some have suggested that it stems from Dewakang Island, an important navigational landmark between Sulawesi and Java. Dutch records from the 18th century mention letters from Sulawesi arriving in Batavia ‘per Paduakkang’.

Dutch records of 1735, mentioning letters from Sulawesi arriving in Batavia ‘per paduakkang’. Image: Nationaal Archief Nederland, 1.04.02.8207: 13

The origins of the word may be older still, with a possible connection to the Austronesian root word waŋka, meaning canoe or boat (for more on these early canoes, take a look at Edwin Jr Doran’s book, Wangka: Austronesian Canoe Origins).

In the 20th century, padewakang were replaced by pinisi – the famous Indonesian sail trader that has come to symbolise the country’s maritime traditions. One of the challenges thus lay in designing an authentic replica of a long-vanished vessel. Early photographs, drawings and textual references came in handy here.

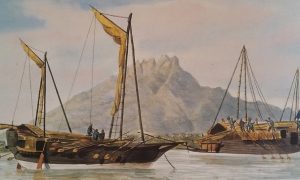

Early padewakang photos, such as this one, were used to design the vessel on display at La Boverie. Image: Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen

The padewakang has many similarities to the vessel used by the naturalist Alfred Russell Wallace to travel from Sulawesi to Aru (Maluku Province) in December 1856. In Chapter XXVIII of The Malay Archipelago, Wallace goes into detail about the materials, techniques and ‘rude practical skills’ required to build these vessels, which, if you are passionate about boats, is definitely worth reading.

However, if you don’t know your adze from your axe, just check out this short video to get an idea of the level of skill required to produce tightly-fitting planks – and then extrapolate this to the construction of an entire vessel.

The padewakang at La Boverie was constructed using the tatta tallu blueprint. Also known as the ‘three-times cut’, this is a type of construction plan that was, until recently, in common use amongst Sulawesi’s master shipbuilders. This technique is characterised by raising the hull’s plank shell prior to inserting its frames, and is in marked contradiction to the ‘frame-first’ approach common in more recent European boat-building traditions. The tatta tallu plans are not drawn but are outlined on a length of bamboo that ‘contains’ a hull’s overall draught, and are implemented by marks on the keel and planks (you can download a short explanation about this here, courtesy of Liebner).

Many of these markings are devised and applied through various ceremonies that mark the various stages of the construction. Ridwan Mandar has a whole collection of beautifully-produced videos on his YouTube channel about the padewakang at La Boverie, including this one showing one of a number of construction ceremonies.

This ‘hull first’ approach determines the position, size and shape of the vessel’s various planks and frames, and even stipulates the positions of the thousands of wooden dowels holding the parts together. It draws on highly specialised knowledge and sophisticated cognitive efforts, and illuminates the importance of embodied and conceptual knowledge in traditional boat-building practices.

Such skills and knowledge are also evident in the selection of the timbers used to construct each vessel: rather than bending each piece of timber to suit their purposes, the boat builders instead seek out gently-curved trees that will yield the shapely planks and frames needed.

The vessel is not simply a replica – it is intangible heritage rendered tangible.

The finished padewakang near-fills the exhibition room at La Boverie. Image: The Jakarta Post / Museum Nasional

While the padewakang references Indonesia’s sophisticated maritime traditions, the future of the vessel itself is undetermined once Les Royaumes de la mers finishes in early 2018. There are plenty of museums around the world with Southeast Asian vessels in their collections: Singapore’s Maritime Experiential Museum, the Samudra Raksa near Borobudur in Java, and of course our very own Australian National Maritime Museum. Any takers?

***

This exhibition is presented with the scientific support of the Royal Museum of Mariemont, Pierre-Yves Manguin of the École française d’Extrême-Orient and the GRIP (Group for Research and Information on Peace and Security). The exhibition is on until 21 January 2018.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss