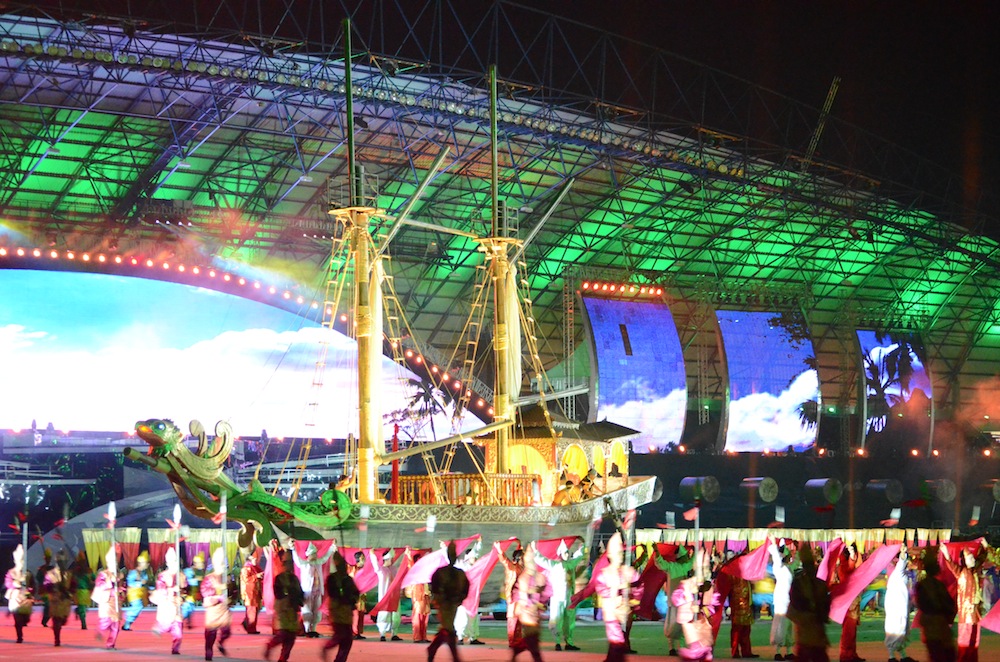

Momentarily, at least, Friday night’s opening ceremony of the SEA Games in Palembang drowned out talk of unfinished venues, inadequate accommodation, and the other things that have marred the lead up to these games. I saw it from ground level, and that was impressive enough. The birds-eye or TV view, for which these extravaganzas are designed, was something else again. You can see it on YouTube here.

There were hiccups. A light shower, ominously for some, became a heavy one just as the Indonesian team entered the stadium, which caused audio problems during the speeches and seemed to extinguish the torch before the flame was lit. But the sound returned and the flame was somehow ignited, meaning these took little away from the extraordinary sound and light show, and nothing at all from the dazzling fireworks.

Predictably enough, the media is split on whether the spectacular opening represented a sideshow to the real story of poor organization, or heralded the end of this saga and the beginning of a successful SEA Games. For what it’s worth, both are probably true. Pride remains palpable in Palembang in spite of traffic problems and a litany of other complaints. But here I want to reflect briefly on the theme of the opening ceremony, the story of the Sriwijaya kingdom.

It was little surprise that Sriwijaya would be the theme of the ceremony and the games more generally: references to the kingdom are ubiquitous in Palembang, where it provides the basis of provincial identity and tourism. But as always with mass history on the scale of an opening ceremony, questions arise. Early in the performance, the announcer proclaimed:

The island of Sumatra was once the centre of one of the biggest kingdoms of Indonesia, the Kingdom of Sriwijaya. In Sanskrit, Sriwijaya means victorious. The Kingdom of Sriwijaya is known as Swarnadwipa, the Golden Peninsula, the heart of Indonesia. With the hope of once again achieving the same glory, the grand sporting event in Southeast Asia, the 26th SEA Games, is staged in Palembang. Ladies and gentlemen, the journey begins.

The Golden Peninsula has great currency in Southeast Asian history and historiography. In Thai and Lao it is literally laemthong and is largely contiguous with Suwannaphum (from Pali), which refers to a mythical golden land mentioned in Hindu texts. In the Siamese/Thai versions of the myth, the golden land stretched across mainland Southeast Asia with the Siamese ascendent. With varying degrees of intensity, the myth has been parried into the service of nationalist historiography as historians have argued for their country’s historical leadership and domination of mainland Southeast Asia. But there are other versions of the myth focused on other countries (see Eisel Mazard’s post here). One of these is Swarnadwipa, which, according to Pierre-Yves Manguin, can also mean golden island and is an old Sanskrit name for Sumatra.

The golden peninsula motif also has special relevance to the SEA Games. When the sporting event was founded by Thailand in 1959 as the South East Asia Peninsular (SEAP) Games, it was known in Thailand and Laos as kila laemthong, the Golden Peninsula Games. This has considerable significance for post-war regional history and politics in Southeast Asia, but most important here is the geographic exclusiveness of the name. Whether or not Indonesia had wanted to join the SEAP Games, the Thai geography of laemthong excluded the archipelago from the event. Indonesian and Filipino efforts to join the games in the late 1960s and early 1970s were rebuffed as Thailand insisted that the games were a “small family affair”, i.e. of the mainland countries (though Singapore competed). Indonesia would have to wait until 1977 to join, when, after the Indochinese countries withdrew, the event was expanded to ensure its survival and renamed the SEA Games.

The opening ceremony suggested the motif of the golden peninsula is poignant once more in the SEA Games. However, this time it is Indonesia putting it to work — at sub-national, national and regional levels. In Palembang and South Sumatra, the Sriwijaya SEA Games or the new Golden Peninsula Games, as we might tag them, reflect local leaders’ efforts to boost the city’s standing in national affairs and attract national resources. At the national level, meanwhile, invoking the mythical golden land of Sriwijaya draws parallels with a new golden age for Indonesia after the years of political and economic turmoil. This is the key theme of the games, as I have discussed. The link between these past and future golden ages was alluded to several times during the opening ceremony. In case spectators missed the commentary, a dazzling laser-light animation and song reinforced it.

Finally, as Indonesian president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono declared in his opening speech, the SEA Games aim officially to strengthen the togetherness of Southeast Asian countries. ASEAN, he added, “has increasingly become a dynamic area and full of progress. Let us increase the cooperation and partnership to achieve a higher-East Asia of peace, justice, progress and prosperity” (translation from here; East Asia presumably refers to ASEAN+3). Though SBY did not say it, Indonesia also sees this year’s games as an opportunity to reclaim its rightful place as leader of ASEAN. According to this objective, the golden peninsula theme also represented the vision of a golden age for Southeast Asia led by and centred on Indonesia.

Funnily enough, the younger locals I’ve asked about this know nothing about the Golden Peninsula, or Swarnadwipa, but it seems to have sent them scurrying for their BlackBerries. Such was the interest sparked by the ceremony that “the golden peninsula” trended briefly on Twitter, not only in Indonesia but also worldwide.

I am interested if anyone has anything to add to these preliminary observations, especially concerning the golden peninsula motif in Indonesia. It would also be interesting to learn how this theme of the opening ceremony was interpreted in different parts of the region. The commentator on the YouTube video (from Singapore), linked above, mentioned that Singaporean history extended back to the golden age of Srivijaya, and the golden peninsula (or words to that effect). Did others in the region say similar things, or did they seek to reclaim the Golden Peninsula motif as part of their own history?

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss