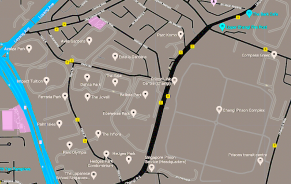

The sun was setting over the Makassar Strait as my plane descended. The Jeneberang River wound through the city below. At the river mouth, I could see the 27-story Delft Apartment tower rising above the delta where shifting sediments had once created a maze of mangroves, mudflats, and waterways. The residential tower, constructed by Ciputra Group as part of its Center Point of Indonesia project, was perched on the claw of an artificial island reclaimed in the shape of a Garuda (see image above).

I was visiting Makassar to attend the opening of the fifth Makassar Biennale, which ran from 9 September to 30 October. The Maritime is Makassar Biennale’s “perpetual theme”, but the recent proliferation of land reclamation in Sulawesi prompted the curators of this year’s event to select a theme of Darat Kian ke Barat, or The Land Moves West. Accordingly, the Biennale exhibited artwork that highlighted the rapid westward advance of Makassar’s coastline.

If Makassar Biennale is less well-known than its counterparts in Jakarta and Yogyakarta, it is not for lack of ambition. This year, the event encompassed five cities, opening in Makassar before traveling to Pangkajene and Islands district and the city of Pare-Pare, both in South Sulawesi, to Labuan Bajo on the island of Flores, and to Nabire in Central Papua.

Each city celebrated a different theme based on the book Riwayat Gunung dan Silsilah Laut (Mountain History and Maritime Genealogy), published earlier this year by Yayasan Makassar Biennale. The book consists of five chapters, one for each location, prepared by research teams affiliated with Makassar Biennale. (I was involved in the research for Makassar, which received funding from the Environmental Justice and the Common Good Initiative at Santa Clara University.) Documenting shifting relationships between land and water, settlement and migration, each chapter represents a summation of the Biennale theme for its corresponding location.

Anwar Jimpe Rachman and Fitriani A Dalay are the thoughtful and soft-spoken couple who organise Makassar Biennale. Originally from the town of Rappang, they now live in Makassar where they have built an ecosystem of artistic, publishing, and research organisations that empower local students, writers, and activists to document and appraise the region’s history and culture.

At the Biennale, artists celebrated Sulawesi’s cultural connections between land and sea and explored themes of loss, risk, and transformation. The works were installed at three different venues, namely Rumata ArtSpace, Artmosphere Studio and Cafe, and Siku Ruang Terpadu. The opening ceremony was held at Rumata ArtSpace, where a signboard directed visitors into a large outdoor event space by way of a narrow alleyway. The stenciled face of Munir, the assassinated human rights activist, smiled from the back wall. In the corner, a stage supported a three-meter-long model phinisi boat, complete with sails. Rumata’s café bustled with activity, and attendees sat cross-legged on tikar mats on the ground. The crowd was largely populated by young Indonesians, both women and men.

A troupe of dancers attired in reds and yellows opened the ceremony with a performance of the Tari Padduppa. The women wore headdresses and carried fans, while the men wore sarongs and passapu head coverings. After the performance, Ms. Fitriani took the stage to inaugurate the event. She invited the curation team to the stage, followed by the participating artists. Then, the lights dimmed for musical performances by Pelakor, Vinale, and D’Elite. Each of these groups performed original songs that they wrote in response to Mountain History and Maritime Genealogy.

The doors to the gallery were opened last. The space was brightly lit, with high ceilings, unpainted walls, and a smooth cement floor. As visitors entered the spare environment, they were immediately confronted by Moelyono’s Suara Jiwa Padewakang (the Voice of the Padewakang’s Soul), in which a four-meter-long model keel of a long-distance padewakang ship was suspended from the ceiling (Figure 2). Offerings were balanced on the skeletal ship, a sandy beach covered the floor, and a ghostly recording chanted mantras in a low voice. The work reinterpreted the centuries-old rituals that sailors performed for protection on long voyages to harvest trepang (sea cucumbers).

Figure 2: Moelyono, Suara Jiwa Padewakang, 2023 (Photo credit: art.e.fact)

Turning to the right, Makassar’s twenty-year spatial plan was splashed on the wall, reclamation zones glowing in red, blue, and green (Figure 3). The city planners’ angular vision of the future was contrasted against schoolchildren’s imaginative drawings of the city shoreline, colorfully arrayed in lines spanning the wall. In doing so, Alifah Melisa’s Mangarra Bombang critiqued city planners’ presumption that they are the authors of the future coastline. On the back wall, Mimpi Buruk Pesisir People (Coastal People’s Nightmare), by Yahyakhan Natadias, exhibited darkly humorous visions. Cartoonish drawings with witty captions illustrated prophecies of polluted beaches, dead corals, jobless fisherfolk, and obscured sunsets. Finally, at the back of the space, future visions were inverted in Jim Abel’s Gementee Makassar (Makassar Municipality). Black and white photographs of Makassar’s past lined the wall, while a city map, constructed from a mosaic of archival materials, conflated history and geography.

Across town at Artmosphere Studio, a curtain enclosed a room with no furniture. Fishing gear hung from the corners of the room, framing a television screen against a white wall. The screen played Ketika Laut Semakin Menjauh (When the Ocean Moves Away), a short film by Sokola Pesisir. The film depicts the developments that have transformed the Jeneberang Delta by interspersing recent video of the Center Point of Indonesia with 15-year-old footage that one of the participants had recorded as a child.

Figure 3: Alifah Melisa, Mangarra Bombang, 2023 (Photo credit: art.e.fact)

These exhibits articulated the sense of loss and anxiety that coastal communities in Makassar have experienced as massive land reclamation projects disrupt livelihoods, communities, and the environment. The Makassar City Spatial Plan anticipates that land reclamation will expand the city area by a whopping 26% (Figure 3). In this context, the 157-hectare Center Point of Indonesia project is just the tip of a 4,500-hectare iceberg. The Makassar New Port project will construct a colossal container terminal on 1,428 hectares of reclaimed land, and the Economic Strategic Areas abutting the Center Point of Indonesia will reclaim hundreds more hectares of land along Makassar’s southwestern coastline.

The Makassar city government’s ravenous appetite for reclamation echoes developments throughout Indonesia. In 2019, there were 197 reclamation projects in Indonesia, according to data from the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries. Reclaimed land serves to facilitate urban expansion into wetland and maritime “hinterlands” for the construction of ports, industrial facilities, commercial areas, and multi-use “waterfront cities”. The projects are highly profitable for the international dredging companies that reclaim the land and the real estate companies that develop it, and they are welcome sources of economic activity and tax revenue for local and provincial governments. However, reclamation projects generate considerable environmental and social costs that disproportionately burden coastal communities. They dispossess communities living within project footprints; seal off access to the sea for fishers and fish traders; disrupt and sometimes erase inshore fisheries; degrade coastal ecosystems, including mangrove forests, mudflats, and seagrass meadows; redirect flows of sedimentation, causing erosion; and reconfigure local hydrology, potentially displacing flooding to neighbouring communities.

Of prison blocks and condos

On the sidelines of Changi Prison lies a fissure in an environment engineered to “invisibilise” Singapore’s social divides.

These dynamics are currently unfolding on Laelae, a tiny island and fishing village located one kilometer from the Makassar shoreline (Figure 4). The South Sulawesi provincial government has granted a permit to reclaim a land bridge connecting Laelae to Center Point of Indonesia. Local islanders strongly oppose the plan, which they fear will prompt evictions and decimate their fishery. They have enlisted the support of local NGOs, such as Walhi (Wahana Lingkungan Hidup Indonesia, or The Indonesian Forum for the Environment), to engage the provincial government in negotiations. They have also circulated a petition and organised demonstrations to publicise their opposition.

Figure 4: Pulau Laelae (Photo credit: art.e.fact)

A few weeks ago, the islanders staged the Songkabala, an annual ritual to ward off disaster, or tolak bala. This year, the ritual took on the added burden of tolak reklamasi. In conjunction with the Songkabala, Makassar Biennale sponsored the dance troupe Gymnastik Emporium as artist-in-residence on Laelae. The troupe collaborated with the islanders to choreograph a theatrical dance performance that dramatised their struggle against land reclamation (Figure 5). The performance, which took place on 15 September, attracted hundreds of visitors who witnessed Daeng Bau, an islander and participant in the Songkabala, pronounce, “We do not wish to be separated from the sea and the coral.”

Figure 5: Songkabala Lae-Lae!, a theatrical collaboration between the Laelae community and Gymnastik Emporium (Photo credit: art.e.fact)

Many residents of Makassar share Daeng Bau’s sentiment that reclamation is threatening a long-established and deeply felt cultural connection to the sea. That sense of loss is hard to capture in a scholarly article, but artists are well-equipped to express it. To that end, Makassar Biennale provided a forum for artists working in many different mediums to explore the cultural impact of land reclamation. The musical group Pelakor offered their perspective on reclamation in a song titled “In Exchange,” written for Makassar Biennale. The lyrics, presented below, have been translated from the original Makassarese:

Our village is prosperous and full of hope.

It appears peaceful to other villages.

But a time came when we humans forgot to take care of our village.

But what has happened? We just filled in the waters, until the ocean was gone.

Let us take care of our village together so that we can live peacefully with the world.

The roar of the waves is no more, lost because of our actions.

The things that fill the ocean are so far from what they should be.

But what has happened? We just filled in the waters, until the ocean was gone.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss