Part 2 of a three-part series, Crossing Borders: Chinese Agricultural Investment in Southeast Asia, this post considers the complexities of Chinese rubber plantations and sovereignty in northern Laos. Part 1 examined northern Burma while part 3 will look at southern Laos.

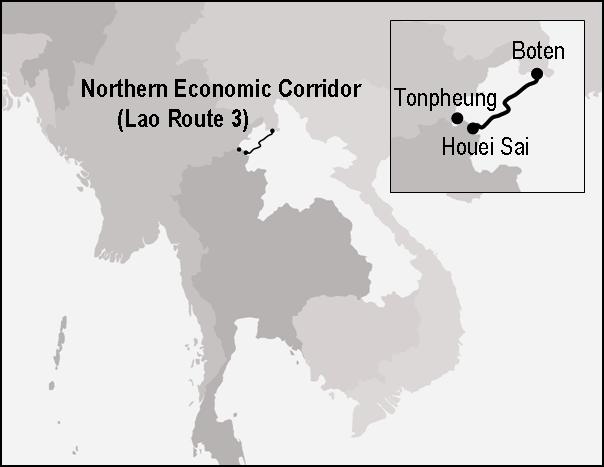

Over the last few years, the borderlands of northern Laos have been much in the news. If most of the initial interest was on the combination of infrastructure and Chinese agribusiness that flowed into Laos (especially Luang Namtha province) in the mid-2000s,[1] recent attention has focused on a pair of Chinese casinos that sprung up in the last few years in Boten and Tonpheung, at either end of the so-called Northern Economic Corridor (Fig. 1). As the casinos have turned ugly – drugs, prostitution, money laundering, even kidnapping and torture[2] – they have re-raised a question that hung in the air during the earlier investment boom: Is northern Laos turning into Chinese territory?

Fig. 1. Northern Lao borderlands

Using Laos’s northern borderlands as their empirical launching pad, the anthropologists Chris Lyttleton and P├бl Ny├нri have recently suggested that colonial-era “extraterritoriality” in coastal China has much to tell us about China’s so-called peaceful ascent today.[3] Noting the parallels – and in particular the uncomfortable mix of humiliation and modernization – between the colonial-era treaty ports and a growing archipelago of Chinese development zones in the global south, Ny├нri and Lyttleton posit a “return of the concession” exemplified by the casinos at Boten and Tonpheung. Walking around Golden Boten City, they are told “Sure it’s China! China rented it”, and put this slippage from property to territory in general terms:

It appears that the environment simply feels too foreign for small Lao entrepreneurs, unfamiliar with Chinese business practices, to move in, and that both proprietors and visitors see the place as a kind of liminal Chinese space…rather than a foreign destination.[4]

Citing a range of other locations – the Special Regions of Burma’s Shan State (see Woods, Part I), the mountains of northern Cambodia, the Lake Victoria East Africa Free Trade Zone, to name a few – Ny├нri and Lyttleton see the casinos at Boten and Tonpheung as pieces of “a remarkably similar silhouette of extraterritoriality” that is, as Ny├нri put it in a 2009 lecture, “emerging around Chinese concessions in various places in Africa, Southeast Asia, South America and the Pacific as China becomes an increasingly significant overseas investor and development aid donor.”[5]

Last December, only weeks after the publication of TNI’s “Alternative Development or Business as Usual? China’s Opium Substitution Policy in Burma and Laos” (see Part I), the Asia Times Online made the somewhat inevitable – but nonetheless dubious, as I will explain – leap from the special zones along the border to the rubber fields of Laos’s northwestern interior. Taking a page from Lyttleton and Ny├нri, the Times Online’s Southeast Asia Editor uses a traffic accident at the casino in Boten to anchor his article’s more expansive thesis: “The absence of any uniformed Lao police officers underscored the authority gap in a growing number of areas in the country where Vientiane has effectively ceded sovereignty to Beijing.”[6] In the analysis that follows, TNI’s report figures centrally, providing much of the backup for the Times Online’s account of China’s “exploitive expansion” beyond the special zones along the border.

In northern Laos, China’s expansion is especially visible in the mountainous areas south of Boten, where once forested areas have been cleared for monoculture rubber plantations managed by Chinese companies. Those companies frequently receive tax waivers and subsidies from Beijing as part of a wider policy to combat opium cultivation and better integrate remote Lao and Myanmar border areas into wider regional markets, according to the Transnational Institute (TNI), a Netherlands-based international network of researchers and activists.

In a November briefing paper, TNI wrote that while “initially informal smallholder arrangements were the dominant form of [rubber] cultivation in Laos, the top down coercive model is gaining prevalence” and that “the poorest of the poor … benefit least from these investments.” The study also noted that many Lao agrarians “were losing access to land and forest” and “were being forcibly relocated to lowland areas that offered few viable options for survival” to make way for Chinese plantations.[7]

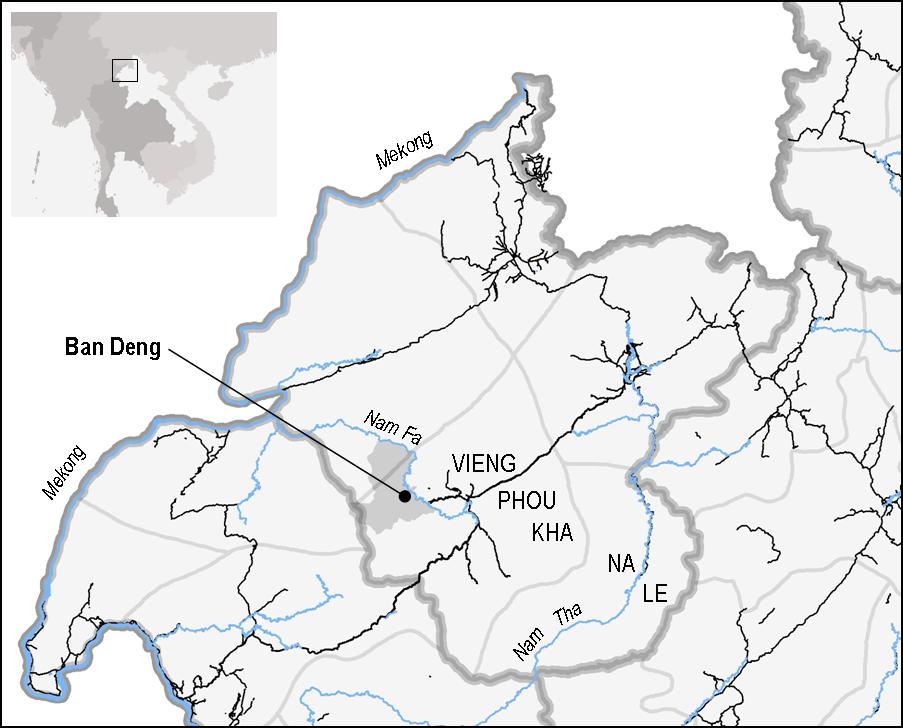

In late 2007, about a year before Luang Namtha’s rubber planting boom slowed down, I visited a village that was in the process of being enrolled into these projects. My experience causes me to question claims of growing Chinese sovereignty over Laos’s upland interior, and emphasizes the complexity of the relationship between Chinese investment projects, dispossession and resettlement.[8] This village, which I will call Ban Deng, highlighted the need to look specifically and historically at not just particular projects, but even particular parts of particular projects.

The picture that emerges is hardly one in which Beijing is displacing Vientiane as the seat of sovereignty in the Lao hinterland. On the contrary, Ban Deng is a case of what I suspect may be a larger phenomenon: local governments’ use of Chinese investment projects to improve their own effective sovereignty – in this case, to help anchor various communities in place along what I will describe as a sort of internal frontier.[9] This was certainly linked to China’s economic expansion into Laos, and it certainly seemed poised to provide what economic geographers call a spatial fix for China’s land problem.[10] But to gloss it as an expansion of Chinese sovereignty is to miss the point entirely.

––––––––

Ban Deng sits out at the end of a well-worn, but fairly recently-built dirt road, about an hour’s motorbike ride from the center of Vieng Phou Kha district (Fig. 2). It is a new village, at least in one sense. Ban Deng was established in 2003 by Khmu migrants from the neighboring district of Na Le, who had been enticed to make the move by their former district governor – a man who, rumor had it, had been rotated to the governorship of Vieng Phou Kha in order to bring “people like them” into the district. One development worker described Ban Deng’s residents as what government officials called “the right kind of Khmu”, a reference to both their place of origin – the east bank of the Nam Tha River – and their ethnic sub-group – which was Khmu Rok. According to Goudineau et al., the Khmu Rok were “a special case” because, in contrast to other Khmu sub-groups in the area, they had become “politically integrated” quite rapidly after 1975 and had received preferential access to development – including land – as a result.[11] Ban Deng, in other words, reflected the geographic legacy of Indochina Wars[12] and was the result of a provincially-coordinated effort to bring the communist heartland of eastern Na Le to the western frontier of Vieng Phou Kha.

Fig. 2 Ban Deng and surroundings

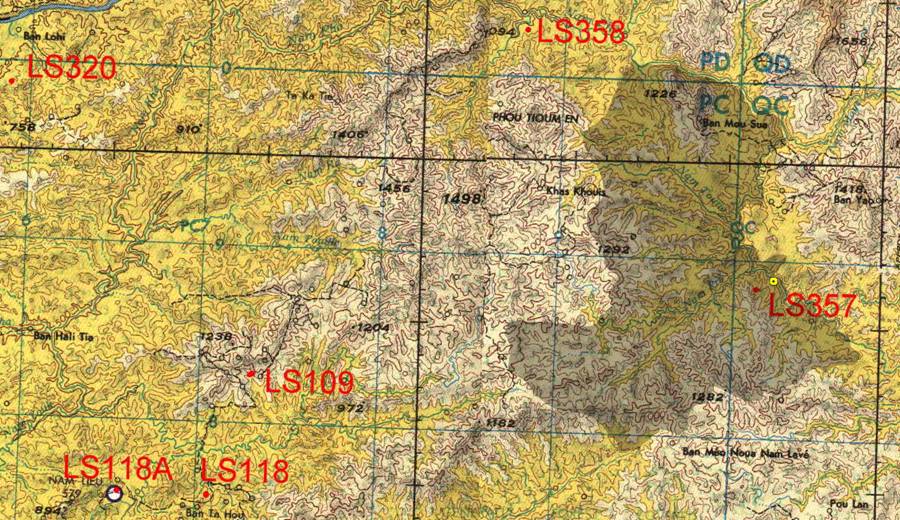

In another sense, however, Ban Deng was much older. As American military maps confirm (Fig. 3), the village site that became Ban Deng was formerly known as LS 357, a remote mountain airstrip established sometime between 1962 and 1973 by the CIA as part of its clandestine war efforts in northwestern Laos.[13] Sitting in the hills to the west of what old French maps call the Yao Mountains, Ban Deng’s location was sat in a part of the district that was formerly home to the Iu Mien (“Yao”) people and had in the 1990s been classified – as if to anticipate Ban Deng’s establishment – as “a priority development zone for the district.”[14]

Fig. 3. Ban Deng, then and now. This map shows Ban Deng’s current village territory overlaid on top of an American military map of the area.[15] The yellow point above LS 357 is my GPS point from Ban Deng. LS 118A is the old CIA base at Nam Nyu.

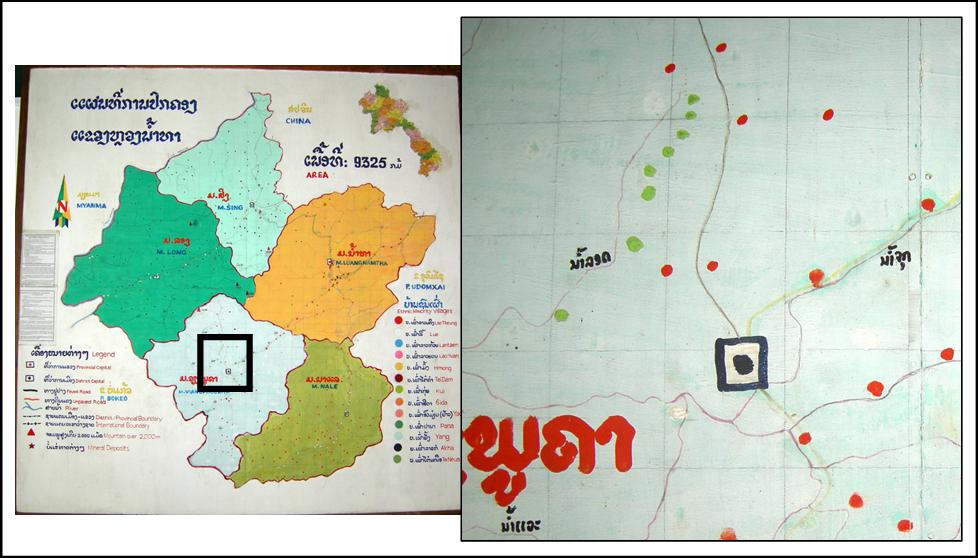

A 2005 district government report noted that Ban Deng was established due to a shortage of productive land at the migrants’ old village site in Na Le. Ban Deng, in contrast, seemed almost endless. Not only was it on the edge of the district, and the area to the west sparsely (if at all) populated; its official zoning map measured the village territory at 9,304 hectares, the largest in Vieng Phou Kha district by far. This spilled over into villagers’ attitude toward land use. The report mentioned above noted – after reporting on a range of development parameters – a single “challenge”: “some of the villagers did not yet understand the Land and Forest Allocation exercise” that had been conducted in 2004-05, roughly a year after Ban Deng was established. When I visited, this lack of “understanding” seemed to have been practically formalized; the village’s official zoning map, created during the aforementioned Land and Forest Allocation exercise, had been recently covered up with posters. Instead of instructing Ban Deng’s residents about where they were and were not allowed to farm, it was now reminding parents to keep their children vaccinated (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Ban Deng zoning map, late 2007

Ban Deng’s residents, it seemed, were being given relatively free rein on how to make use of their village territory, and in particular where to plant their crops. A pair of soldiers based in the village had recently planted a few hundred rubber seedlings, for example. An ex-government employee who also lived in the village lamented the unruliness of his compatriots, but told me that controlling their farming practices was not a high priority – at least not by coercive means. In fact, cultivation in Ban Deng had an expansionary feel to it. On top of the soldiers’ experiment, villagers had recently had their first meeting with the local Chinese rubber project, an import-export firm that had been approved to “promote” contract farming in the district. As they waited for company representatives to return, they were mulling over the pros and cons of independent smallholder production versus contract farming. Rubber was coming to Ban Deng. But the degree to which “the Chinese” were coming along with it was another question entirely.

––––––––

On the way to Ban Deng from the district center, I had passed through three other villages that had a very different relationship with the rubber company. Unlike the residents of Ban Deng, they had not been offered much of a choice about whether or not to contract with the project, and the nature of their contracting arrangement was different as well. In contrast to the latex-sharing model that other villages in the district were being offered, these three had been selected by the district governor as “tree-sharing” villages. Village land had thus been treated collectively by the project, and villagers hired to plant rubber seedlings on a vast expanse of land (Fig. 5), thirty percent of which would eventually be given back to them when the trees matured. The company would retain ownership of the trees on the other seventy percent. This landscape – a company plantation in the short term, a mixed “core-outgrower” landscape of company- and contractor-owned trees in the longer term – lined either side of the road to Ban Deng. Over the two years prior to my visit, this area had gone from a swidden landscape to the heart of Vieng Phou Kha’s rubber zone.

Fig. 5. Rubber plantation on the road to Ban Deng

A district government representative explained to me that this arrangement had been crafted by the district governor, presumably the same person who had recruited Ban Deng’s residents. He told me that these three villages were the poorest of the poor,[16] and explained their exceptional status in ethnic terms. They were comprised of Lahu (he used the derogatory term Kouy) people who, in local officials’ estimation, were too poor to be contract farmers because they could not afford the long wait between planting and harvesting.[17] Instead, they worked as day laborers – ha sao, kin kham or “work by morning, eat by night” in the local idiom – doing planting and clearing for the rubber company, and cultivating swidden fields further out in the bush (Fig. 6). The rubber plantation work, he explained, and the tree ownership that would follow it were designed to provide permanent livelihoods for the three Kouy villages; with this arrangement, the district administration was attempting to counteract the ethnic group’s proclivity for abandoning the government-established villages along the road and “going off into the forest” to live among their swidden fields.

Fig. 6. Swidden fields on the edge of the company rubber plantation. Arrows point to traditional Lahu rice stacks.

This “off in the forest” was not just a geographic abstraction; it was the frontier where Ban Deng was, and beyond (see Fig. 3, which includes a “Khas Khouis” settlement just west of the current territory of Ban Deng). Through a mix of sources, I came to learn that the area being settled by Ban Deng – as well as by a second, also very large, village just to the south – had been formerly occupied by not just the “Yao” people, but by the Lahu, a Tibeto-Burman ethnic group made famous via their Cold War ties to the CIA.[18] This earlier discourse of collaboration with the enemy[19] had been replaced by a one of more general ungovernability. Although I did not dig too deeply due to political circumstances explained below, there was an uneasiness to the way local officials dealt with Lahu (re)settlement. Getting them to “settle down” and stop growing opium (a standard goal of minority policy discourse in Laos) was only part of it. Placement and size were essential as well. The three villages on the road to Ban Deng were relatively close to the district center and were lined up along the road, as if for easy observation (Fig. 7). It seemed an odd coincidence that the Lahu were involved in one of the more alarming rubber projects in the province – a large Chinese concession that spilled from military land onto the adjacent land of a Lahu village.[20] Just south of Ban Deng, a Lahu settlement had also been broken up and prevented from reassembling itself because, as one consultant cryptically put it, “the government said they would not accept a large ‘new’ Lahu village.”[21]

Fig. 7. A map in the provincial government museum projects a desire to have Lahu villages (green dots) lined up regularly along the road just north of the district center.

This uneasiness spilled over into urban affairs as well. During my tenure in Luang Namtha, northwestern Laos underwent an anti-American and anti-Christian crackdown that led to at least two Lao disappearances and, according to a recent accounting, the departure of roughly 26 foreigners.[22] Although I was mostly untouched by this, my research activities were curtailed at least once because of my identity as an American, and I was warned – jokingly, but with a hint of seriousness as well – that I might want to identify myself as being a different nationality.

———-

Sovereignty – politics with a capital P – does in fact loom large in the rubber fields of Laos’s northwestern interior, and it does so in ambiguous and multivalent ways. It was beyond my capacity to adequately chart the relationship between the ethnic geography of the upland frontier and the politicization of national and religious identity that was going on in the provincial capital. But the development and deployment of Chinese rubber projects by local officials seemed to span both of these. Where was the line between the “real” threat (to the government? to profitable investment?) and the instrumental use of the past to achieve economic ends? It was difficult to say. What was clear, however, was that the territorial dimensions of Chinese agribusiness, and the questions of sovereignty that accompanied them, were less national in scale than they were provincial, in both senses of the term. The frontier in question was not an unregulated expansion of China into Laos; as the case of Ban Deng shows, the transformation was quite carefully orchestrated, and the identities involved were locally rather than nationally referenced. Chinese investment certainly was playing its part, offering a way to anchor the villages of western Vieng Phou Kha into their appointed places. But the overall logic – from the placement of the villages to the contracting model assigned to each – was the product of a sovereign power that far more local, and far more Lao. While Chinese extraterritoriality may help explain the special economic zones along the border, it does not appear to be the main story in Laos’s upland interior. At least not yet.

Mike Dwyer is a doctoral candidate in the Energy and Resources Group at the University of California, Berkeley, and conducted fieldwork in Laos during 2006-08. His research was supported by the Social Science Research Council (with funds provided by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation), the National Science Foundation, and the University of California. He is currently writing his dissertation.

[1] See earlier NM posts by Antonella Diana, Olivier Evrard, Andrew Walker and myself.

[2] Chinese foreign ministry issues warning against gambling in Laos, 26 Mar. 2010; Chinese casino on the Mekong: fears development front for money laundering, Asia News.it, 29 Jan. 2011.

[3] Chris Lyttleton & P├бl Ny├нri, Dams, Casinos and Concessions: Chinese Megaprojects in Laos and Cambodia, no date;

[4] Ibid., p. 8.

[5] P├бl Ny├нri, “Extraterritoriality. Foreign Concessions: the Past and Future of a Form of Shared Sovereignty”, inaugural oration at Amsterdam’s Free University, Nov. 19, 2009; the Cambodia example comes from Lyttleton & Ny├нri, above.

[6] Shawn W. Crispin, “The limits of Chinese expansionism”, Asia Times Online, December 23, 2010.

[7] ibid.

[8] See various NM posts on resettlement in Laos by Holly High, Ian Baird and Bruce Shoemaker and Nicholas Farrelly.

[9] The notion of “anchoring” figures centrally in the earlier resettlement debate. See previous footnote.

[10] David Harvey (The Limits to Capital, 1982, and The New Imperialism, 2003). Also see Kathy Le Mons Walker, 2008. From covert to overt: Everyday peasant politics in China and the implications for transnational agrarian movements. Journal of Agrarian Change 8:462-488.

[11] Yves Goudineau et al., 1997, Resettlement and social characteristics of new villages, UNESCO & UNDP, vol. 2: 26. In contrast, thousands of Khmu from the right (west) bank of the Nam Tha had been involuntarily resettled from Na Le to Vieng Phou Kha between 1975 and 1996.

[12] “The modern district of Na Le was the scene of quite violent encounters between the troops of the Lao Issala on the left [east] bank and the counter-revolutionary guerillas on the right [west] bank. The Nam Tha [River] was a true front line…” (Goudineau et al., 23).

[13] On the secret war in northwestern Laos, see Roger Warner, 1996, Shooting at the Moon and Alfred McCoy, 2003, The Politics of Heroin: CIA Complicity in the Global Drug Trade.

[14] Goudineau et al., 23. On the flight and resettlement of the Iu Mien, see Goudineau et al. and Leif Jonsson, 2009, War’s ontogeny: Militias and ethnic boundaries in Laos and exile. Southeast Asian Studies 47:125-149. The “Yao mountains” are now comprised largely of the Nam Ha National Protected Area.

[15] U.S. Defense Mapping Agency Topographic Center, Washington DC, compiled 1975; map series 1501, edition 3, 1:250,000 scale, sheet NF 47-16 (“Luang-Namtha, Laos; Thailand; Burma”).

[16] Vieng Phou Kha is officially ranked as one of Laos’s “priority poverty” districts.

[17] Variations on this theme appear throughout Luang Namtha, and seem to be a chief rationalization behind the proliferation of tree-sharing arrangements that bear striking resemblance (although potentially important differences as well) to the lease-based concessions that the northern provinces had agreed to avoid in late 2005 (Weiyi Shi, 2008, Rubber boom in Luang Namtha: A transnational perspective. GTZ, Vientiane; Simone Vongkhamhor et al., 2007, Key issues in smallholder rubber planting in Oudomxai and Luang Prabang provinces, Lao PDR. National Agriculture and Forestry Research Institute, Upland Research Development Program, Vientiane).

[18] Gordon Young, 1967, Tracks of an Intruder; McCoy, The Politics of Heroin.

[19] Ian Baird reports an anecdote from 2002 in which a Lahu village about 40 km west of Ban Deng (in the Nam Nyu Special Zone) “disappeared” into the forest and was resettled by the army amidst rumors that “the Americans are back” (In D. Vinding et al., eds. The Indigenous World 2004. International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs, Copenhagen).

[20] Shi, Rubber boom in Luang Namtha, 32-33.

[21] Anonymous. This was a scoping report for a development project that ultimately did not happen.

[22] William Tuffin, 3 Jan. 2011.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss