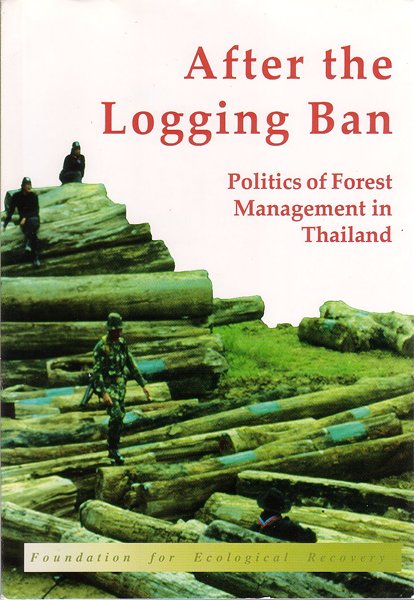

A new publication from Foundation for Ecological Recovery provides a useful overview of Thai forest management since the national logging ban of 1989. The overall argument of the book is that the ban falls a long way short of providing a basis for sustainable and participatory forest management in Thailand.

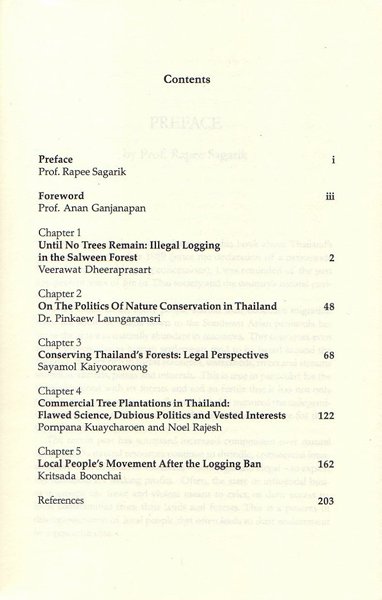

There is not a lot that is new in this volume, but it is a useful overview of key issues and debates. The discussion tends to be framed in terms of a dichotomy between a rapacious state and resistant local communities. Some may find this useful, others less so. Some of the dilemmas facing advocates of community forestry are usefully explored, especially in the chapter by Kritsada Boonchai. How this campaign will pan out in the post-coup era remains to be seen. With the 1997 Constitution gone, Article 46 which granted “rights in the management, maintenance, care and use of benefits from natural resources and the environment in a balanced and sustainable manner” to “persons so assembling as to be an original local community” is a thing of the past. Article 46 was something of a beacon of hope for those campaigning for local resource management rights, but I have always felt that the preoccupation with “original local communities” presented more constraints than opportunities. Where are such communities to be found in contemporary Thailand? And is “originality” really a sound basis for providing resource rights?

But the idea of a return to original values does seem to appeal to some. As Prof. Rapee Sagarik writes in the Preface:

We have lost our spirituality and our intimate connections to nature… As long as the country is shackled to material greed and the endless accumulation of monetary profits, we will continue to lose our precious natural resources… As long as there is no deep-seated change – both social and spiritual – within human beings, the successive cycles of deforestation and degradation of forests and natural resources are bound to continue.

Alleluia!

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss