Friends of mine know I think about food. A lot.

When I look at the edges of my closed, worn copy of The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye, I think of kueh lapis. The striations of colour amongst the white speak an irresistible promise of the dazzling pages within, of the layers upon allegorical layers of storytelling and critical insight. Mmm.

Much has been said about Sonny Liew’s masterpiece, especially after it won three prestigious Eisner Awards in San Diego’s Comic-Con last Saturday – an achievement to parallel Singapore’s success at the Olympics and Paralympics last year. I’m not here to talk about the National Arts Council’s hilariously tepid response to the work (what work? Whosit? Nevermind), which at the time of writing has received 223 ‘Haha’ reactions. I’m also not writing a review (five stars, go buy). I’m revisiting my beloved copy, flipping to the epilogue, and talking about how this crucial, foundational layer alone – a dozen pages or so’s worth – provides us with a whole lot of food for thought about how history is produced (I won’t say written, because history is more than text), and how that’s relevant to us Singaporeans.

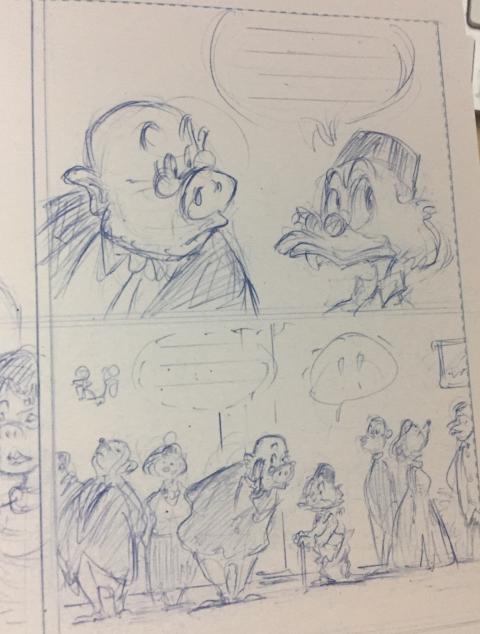

Dato Duck sketch. Photo of partial page (299) taken by me, artwork is Sonny Liew’s copyright.

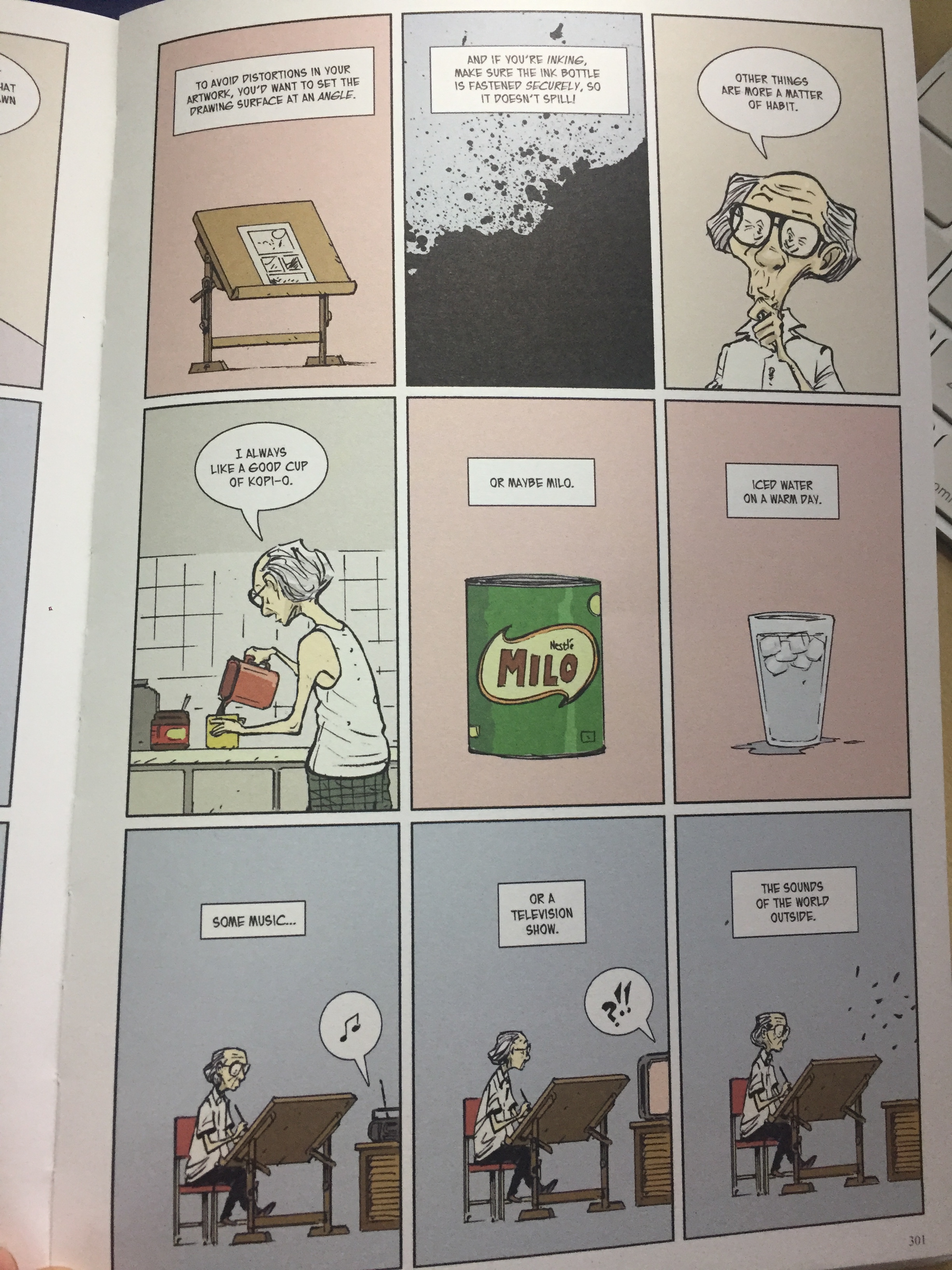

The epilogue, titled “An Old Man Now, After All” and subtitled in Mandarin “野草莓” (‘wild strawberries’; a possible reference to Ingmar Bergman’s 1957 film, an allusion too complex to unpack here), simply takes us through 76-year old Chan’s morning. Chan is still drawing comics, despite having never gained the recognition he deserved. He shows us a page of the latest thing he is working on: a comic called ‘Dato Duck’ about Singaporean financial culture modelled after Carl Barks’ work. The skill shown here is worlds away from Chan’s drawing of a squiggly, misshapen Donald Duck seventy years before as a 6-year old in 1944, the earliest shown in this fictional portfolio. Much has changed since in his life and art, but not the love and passion that drove him to pick up that pencil in 1944. Today, after “all” he’s been through, he is content to drink kopi-o, listen to the world outside, and make art.

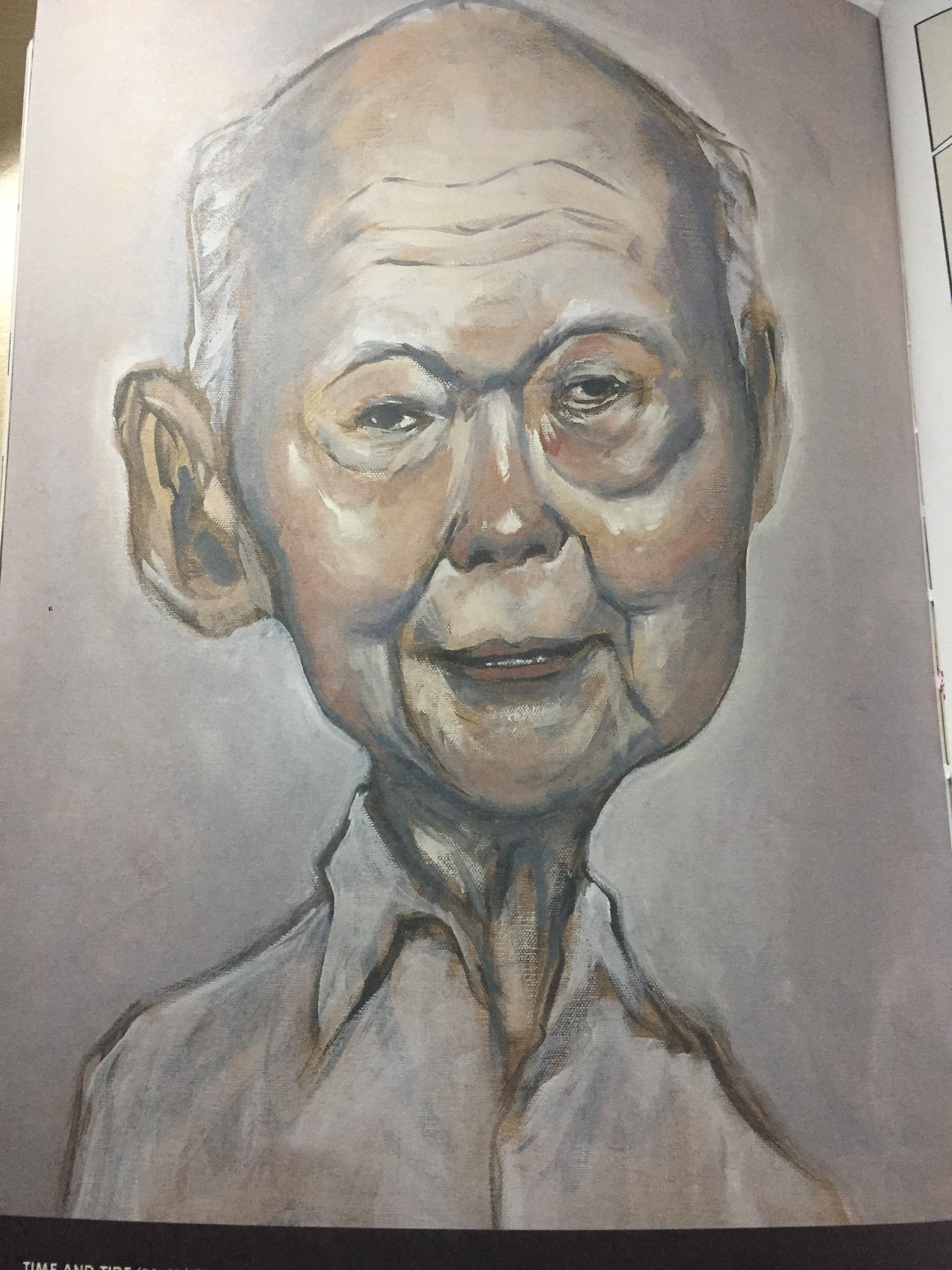

Photo of page 296, artwork is Sonny Liew’s copyright

Unlike the preceding chapters, the epilogue doesn’t have a whole lot of content or critique about Singapore history per se. That said, there is an oil-on-canvas portrait of Lee Kuan Yew at 88 in Chan’s style, with a blurb about his passing and legacy. It is a Lee Kuan Yew with thin, white hair, ruddy pink cheeks, unfocused eyes and a genial smile – a stark contrast to the portrait sixty pages before of LKY in 1970 (deep in the knuckle-duster era), the shadows of his ashen, harshly-angled face steeped in blood-red. That portrait may be the only most direct reference to Singaporean history in the epilogue, but this chapter alludes to the process of making history just as much, if not more, than the rest of the book.

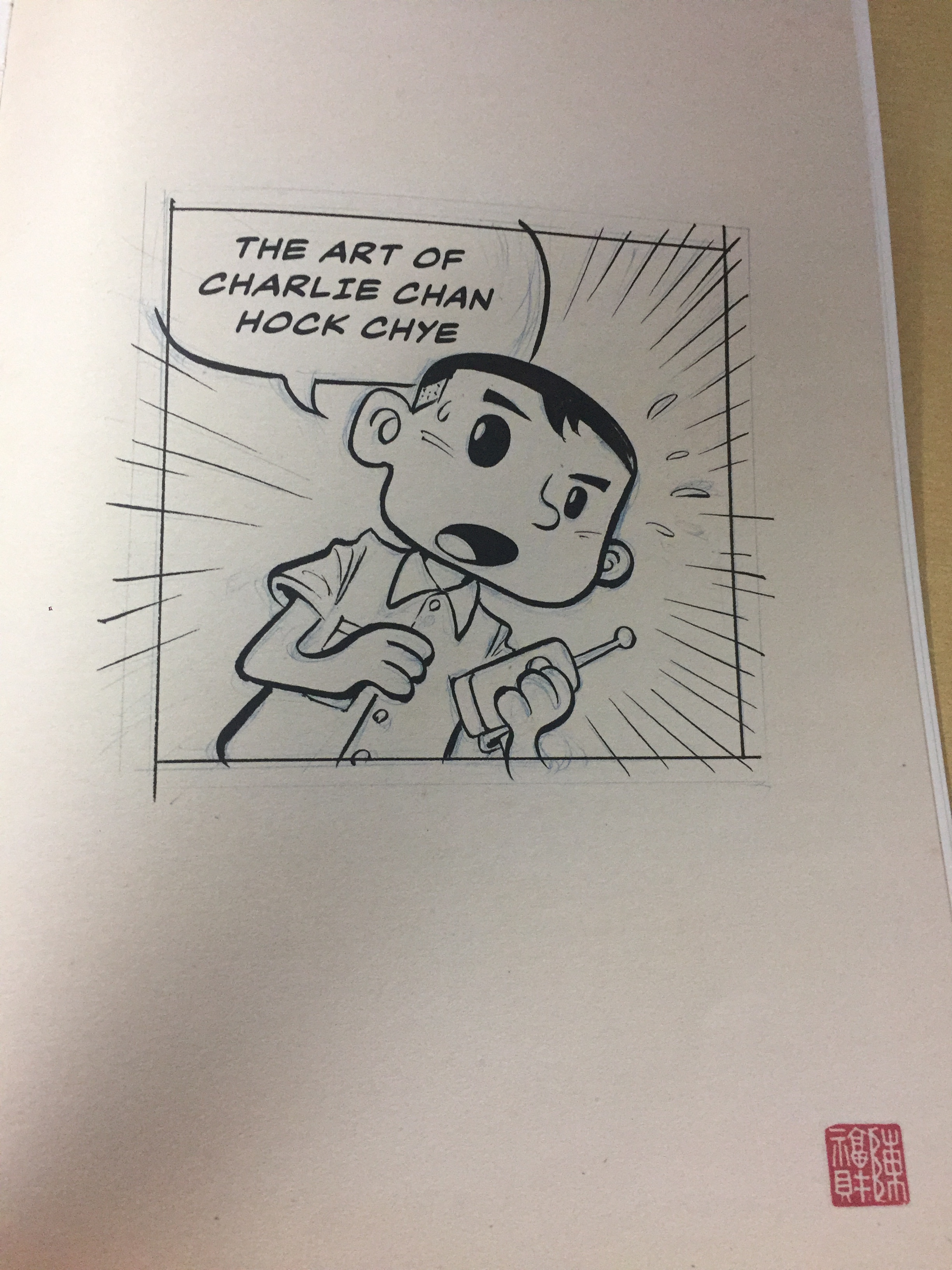

Most importantly, it is an allegory of the fictive process of history-telling. As Chan takes us ‘backstage’, he tells us the way comics are drawn: “using white-out”, “pasting new drawings over existing ones”, setting the drawing surface “at an angle”. Yes, he talks about the finished product (“it didn’t matter so long as the printed result looked good”), but nevertheless shows us a full page of a skeletal rough draft. Nine whole panels are dedicated to depicting Chan’s bony fingers painstakingly taking an inked brush on the sketch of the now-iconic picture of Ah Huat holding the remote control of the robot as seen on TAoCCHC’s cover. The finished outline is on the final page, and the sense of completion seemingly cemented with the red seal of Chan’s signature on the bottom right. But Liew/Chan tellingly does not erase the traces of the blue sketch beneath.

Photo of page 305, artwork is Sonny Liew’s copyright.

Putting aside the well-told fact that TAoCCHC tells an evidence-based revisionist account of Singaporean history through the life and times of a fictional comic artist, the epilogue brings the fictive process of history-making to the fore. Fictive not in the sense that it is fictional, but in the Geertzian sense that it is constructed. This means that one can and should critically examine the circumstances surrounding the construction of histories, and apprehend the possiblity of re-construction. Sonny Liew’s presentation and re-presentation of TAoCCHC is essentially performative/performance-like in this sense, drawing our attention to the framing, making and re-making that is story and history-telling.

The epilogue also shows us that history-telling comes in many different forms. Yes, on the surface TAoCCHC’s genre as a graphic novel most obviously offers to readers the incredible potential – that Sonny Liew utilises to the fullest – of national history conveyed through the art of comics. The epilogue pares that layer back with a handful of simple, no-frills pages that focus on Chan the old man ‘now’ and his everyday life, which reminds me that when all is said and doneTAoCCHC is based upon oral history interviews. The fact that they are fictional interviews adds to rather than detracts from the complexity of the work. Liew made the conscious decision, in this epilogue, to return to the personal life of this man after the grand political narratives that coloured the preceding chapters. Drinking Milo, cooling off, listening to the radio, all those routines are part of history too.

Photo of p.305, artwork is Sonny Liew’s copyright.

I want to end by saying how much I appreciate the way Sonny Liew depicts three-dimensional movement and bodies on the two-dimensional page, and this epilogue is no exception. Behind the scenes (and in the case of performance or oral history, frontstage as well), history-telling/comic-drawing is very much embodied. The nine, three-tiered equal-sized panels that Liew utilises often throughout the book shows a slower, older Chan, each panel usually showing an incremental difference in gesture or facial expression: a turn of the neck, a sigh, a contemplative look. I have delusional fantasies about having enough skill to depict my oral history interviews in this way to ‘embody’ my transcripts for any future listeners.

Not in this lifetime. Maybe I’ll get some kueh lapis instead.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss