Indonesia’s oligarchs are flexing their muscles. But to what extent were they defeated by Jokowi in the first place?

In the latest edition of the journal Indonesia, the Australian National University’s Edward Aspinall details the political career of “oligarchic populist” Prabowo Subianto, noting that the majority of Indonesia’s oligarchs provided support for his presidential campaign.

My article in the same journal examines the ways in which Jokowi became a media phenomenon and most popular candidate for President in all polls in 2013 and 2014, despite not being part of the oligarchic elite – and via media which is owned by the very oligarchs who were also in the running as presidential candidates.

While quite obviously some oligarchs played a significant role in Jokowi’s campaign, the Suharto-era oligarchic power and dominance had been openly and somewhat spectacularly challenged by Jokowi’s victory.

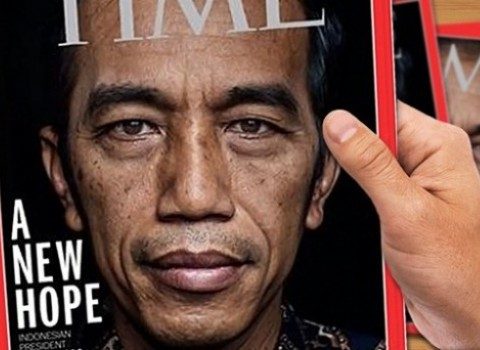

This was epitomised in Time magazine’s front cover of Jokowi with the headline ‘A New Hope’.

What we’ve seen so far in a Jokowi Presidency has shown those oligarchs who supported him have flexed their muscles. At first, it was feared Prabowo’s opposition, the KMP [Koalisi Merah Putih] would be the predominant source of hindrance for reforms.

Rather, Indonesians now joke that it is another ‘KMP’ who are the biggest hindrances – oligarchs who supported Jokowi in the election – Jusuf Kalla [Vice-President], Megawati Sukarnoputri [PDI-P Party Leader], and Surya Paloh [Head of NasDem and owner of MetroTV].

In early 2014 Tempo reported how Surya effectively has the keys to the Presidential Palace. He is said to arrive on occasion four times a day. Recently, the Australian National University’s Liam Gammon wrote of Megawati’s performance putting Jokowi in his place at the PDI-P conference. Jokowi wasn’t even given the chance of talking to the party faithful. Others have seen Jusuf Kalla as aiming for the presidency himself, a concern pointed out when he was on the verge of being nominated as Vice President last year.

Meanwhile, those oligarchs who didn’t support Jokowi are rallying. Hary Tanoesoedibyo has started his own political party, Perindo, and will soon launch a 24-hour news station to rival major networks TVOne and MetroTV. Jokowi was even forced to meet with his vanquished rival Prabowo, as Megawati continued to try to call the shots.

Media mogul Chairul Tanjung’s companies continue to prosper, and former President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono is now a commissioner of a media outlet linked to his company, but he has, to date, been quiet politically since the election.

Only Aburizal Bakrie seems in trouble. His grip as Golkar chief is being contested, and he’s rumoured to be looking at selling stakes in some of his media companies.

Sukarnoputri. Tanoesoedibjo. Kalla. Bakrie. Djojohadikusumo. Paloh. ‘They’re all just spokes on a wheel. This one’s on top, then that one’s on top and on and on it spins.’ (When politics is this messy, a Game of Thrones reference is inevitable).

One is tempted to end with a statement of whether civil society can enable a ‘return of the Jedi’, or whether Jokowi or others might eventually ‘break the wheel’. But I’ll spare you any further popular culture references (because New Mandala is classy that way).

Jokowi’s ascendancy from local Mayor to eventually become President showed a period of contestation in Indonesia’s politics, where rather than submitting to the same old predatory practices of oligarchy, new practices and initiatives to gain political momentum were forged.

His success was to a large extent driven by ‘grassroots’ campaigning and volunteer communities, as well as new media initiatives and the prod-user [someone who produces and consumes media content], and many in the general public who yearned for news of a politician who represented a break from the “old faces” of Indonesian politics.

Certainly, rich individuals will continue to dominate the political economy of the media industry in Indonesia, as they do in many other democracies around the world. But Jokowi’s rise shows that “non-oligarchic or counter-oligarchic actors and groups” negated their power and influence.

The struggle between oligarchic and populist forces will continue, and to a large extent be facilitated by and played out in digital media platforms.

The role of Kawal Pemilu (Guard the Elections), an initiative of civilian Internet users to ‘crowdsource’ voting tabulation around the country, was but one example of these increasingly popular forces enabled by digital technologies.

As Inaya Rakhmani previously wrote for New Mandala, the 2014 elections “show that citizens are sharing knowledge, information and expertise, and often form allies with mainstream media and journalists to guard their democracy”.

At the time, the Indonesian Parliament’s decision to abolish direct local elections (with seemingly tacit support from the then soon to be outgoing President SBY) saw outrage on social media. The #shameonyouSBY was trending worldwide on Twitter, causing much international embarrassment of the then president, who then later implemented strategies to change the decision.

Yet the oligarchs have emerged largely victorious against digital media campaigns in the early stages of Jokowi’s presidency.

The idea to “crowdsource” Jokowi’s cabinet never eventuated, with selection of ministers far more determined by oligarchs, namely the three individuals of the ‘KMP’.

The battle between the police and the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) saw media elites rallying behind police-chief candidate and Megawati favourite Budi Gunawan, and civil society using Twitter to campaign to “save the KPK”. Jokowi made Budi Gunawan Deputy Police Chief, saying that the bid had “evoked different opinions among the people”.

The question is: has President Jokowi given Indonesian civil society enough reason to rally to his cause through these platforms?

Or, at a time when online and social media platforms seem to shorten attention spans, are Indonesians beginning to look elsewhere for a new champion?

We will know soon enough. But for now, there is little doubt that the oligarchs are fighting back.

Dr Ross Tapsell is a lecturer at the Australian National University. He researches the media in Indonesia and Malaysia. Sections of this piece were taken from his article, ‘Indonesia’s media oligarchy and the “Jokowi phenomenon”’ in the journal Indonesia, which you can read here.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss