Ranong Kongsaen lives in a small rural village called Na Nong Bong in Loei province, located on the border of Thailand and Laos. She is also an activist of the Khon Rak Ban Kerd Group, or “People Who Love Their Home”. The group was formed in 2007 to peacefully protest a local goldmine then owned by a Thai company called Tungkum Ltd.

The Khon Rak Ban Kerd Group activists are led by respected women elders, such as Khun Wat pictured here. Behind her are photographs featuring aerial views of the gold mine. Tungkum Ltd. began excavating the land in 2006. Soon after, members of the community reported symptoms consistent with poisoning. In 2009, the Thai government issued a warning to residents to stop using local water sources, and later cautioned against eating river snails and crabs from the area. Randomised blood tests conducted by the Public Health Office in 2010 revealed that 124 out of 725 residents tested had high levels of cyanide in their blood among other toxic chemicals, as reported by Fortify Rights. While chemicals such as cyanide are known to be used in the processing of gold ore, the source of this contamination remains unconfirmed.

Members of the Khon Rak Ban Kerd Group assembled in Na Nong Bong village’s “Centre for Weaving and Mining Action”. With agriculture the main source of income for the majority of Loei residents, natural resources such as water and land have a large bearing on their livelihoods.

Khun Ranong at the gates of the now disused Tungkum gold mine. Community resistance to the mine meant the government did not issue permissions to continue excavating the land after 2012, but residents observed that ore was still being transported out of the mine until 2014. Then, following a lawsuit with Deutsche Bank, Tungkum Ltd. was declared bankrupt in January 2018. The mine and chemicals associated with gold extraction are thought to have been abandoned at the site for several years.

A close-up of Khun Ranong at the gates of the gold mine. She recalls, “Dust from the blasts [at the mine] covered the whole town at night and when we looked out the windows, the visibility was terrible. Black matter covered our roofs, and when the first rain began that season, it became like oil. The environment in this area is no longer good. The chemicals used in the mine harmed us… After they were done, they just left everything. The mine closed, and they left a mountain of rubble, chemicals, pollution. No one has helped restore the land. The damage they have done to the environment is insane.”

A side profile of a section of the Tungkum gold mine. Human rights lawyer Sor Rattanamanee Polkla has represented members of the Na Nong Bong community in lawsuits against Tungkum Ltd. over the loss of their livelihoods from water pollution linked to the mine. She says that all 165 plaintiffs (some of which represent whole families) across 5 cases are yet to receive compensation despite the court ruling in their favour. They are unlikely to see any funds until Tungkum’s assets are sold—a process which is still pending.

Polluted water at the gold mine. Since Tungkum’s bankrupcy, the Khon Rak Ban Kerd Group have turned their attention towards decontamination. Over the last couple of years, several Action Plans to rehabilitate the mine and surrounding land have been drafted by different state departments including the Pollution Control Department and the Department of Primary Industries and Mines, as well as Tungkum Ltd itself. But locals claim that these plans have either excluded or inadequately incorporated the affected community. While negotiations around the rehabilitation action plan continue, the goldmine remains dormant.

A view of the Tungkum goldmine. The giant vats are filled with tons of mining byproducts, including cyanide. Penchom Saetang, a representative from Ecological Alert and Recovery Thailand (EARTH), confirmed that the Tungkum mine used a technique called ‘gold cyanidation’ in order to extract precious metal.

A view inside the vats at the Tungkum goldmine. In a process known as ‘vat leaching’, finely crushed, low-grade ore is mixed with sodium cyanide and water. The cyanide binds to the gold ions and makes them soluble in water, allowing for separation from the rock with the addition of activated carbon.

A close-up view inside the vats at the Tungkum goldmine. Despite being used in around 90 per cent of global gold production, gold cyanidation is controversial due to cyanide’s high toxicity to animal and plant life. Cyanide is not the only chemical used in gold extraction. The Pollution Control Department has been monitoring the Tungkum mine since 2014, and noted that the water in the local area contains higher than safe levels of arsenic, cadmium and manganese.

Part of the now dilapidated control room apparently for cyanide treatment. On the right, a warning sign can be seen providing health and safety information on the handling of sodium cyanide.

The most recent Action Plan drafted by the Thai Department of Primary Industries in December 2019 aims to decontaminate the gold mine and surrounding land in four years. The plan focusses on disposing the tailings pond containing waste materials from the gold extraction process, conducting risk assessments, and investigating the presence of heavy metal in the village water supply and land.

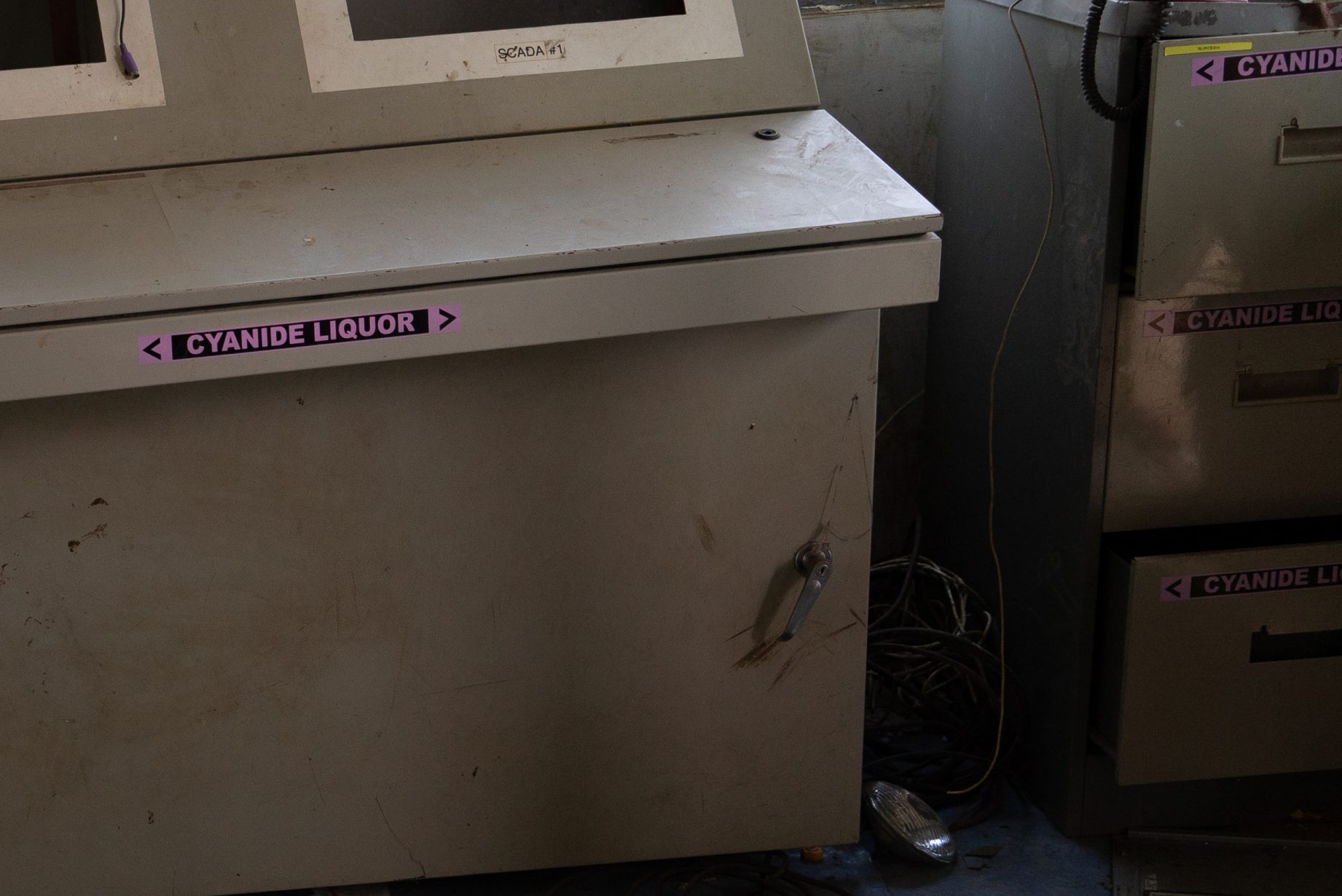

Equipment inside the control room with labels reading “cyanide liquor”. There are concerns that further environmental damage could occur if the chemicals at the goldmine are not addressed soon. While the government Action Plan makes provisions for the disposal of chemical waste, there is no significant focus on preventing harmful mining activities in the area in the future either.

Khun Ranong at the site of the gold mine. The Khon Rak Ban Kerd Group recently met with the Loei District Provincial Governor, Chaiwat Chuenkosum, to discuss whether he would consider lobbying for a community-based approach to the mine’s rehabilitation. Despite over a decade of activism, Ranong and other members of the Khon Rak Ban Kerd Group remain determined.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss