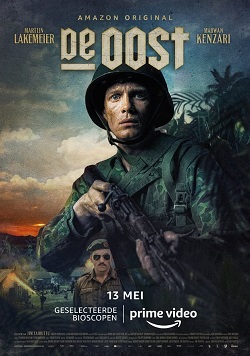

On the 13th of August 2021, four days before Indonesia celebrated its 76th year of independence, Jim Taihuttu’s De Oost [henceforth The East] was released worldwide. This new Dutch film about the Indonesian War of Independence (1945-1949) follows the war volunteer Johan de Vries (Martijn Lakemeier) as he arrives in Indonesia and joins a special forces unit led by “The Turk” (Marwan Kenzari), the historical and controversial figure Captain Raymond Westerling. Even before its release the film was disputed (predominantly by veterans and their descendants) and questioned for its veracity, as Westerling and his men used intimidation, violence and terror in a process that Westerling described as “pacifying the Celebes”. The international trailer summarises it as follows: “At the end of WWII, The Dutch sent troops into Indonesia. Their mission was to crush a rebellion and reclaim a colony. All in the name of peace.”

In an interview with Dutch television presenter Humberto Tan immediately after the online press screening of the film, lead actor Martijn Lakemeier said he was surprised to find out that Indonesian extras were so familiar with the events of the Indonesian War of Independence. From an Indonesian perspective that familiarity comes as no surprise. In addition to being a crucial part of Indonesia’s history, in recent decades a vibrant popular culture has emerged around the occupation and the war of independence. While the Netherlands is clearly still struggling to come to terms with its colonial legacy, Indonesians are widely using popular culture to remember the past—including the Indonesian War of Independence. Film plays a central role in this.

The international release of The East highlights that the remembrance of the Indonesian War of Independence in popular culture is becoming increasingly transnational. The result, however, is composed of cultural objects from various national contexts.

Film perjuangan

Shortly after Indonesia’s independence in 1945, a first wave of war films about the struggle for independence appeared: the so-called film perjuangan or “struggle films”. These films revolve in general around a group of freedom fighters who fight against the Dutch army: the emphasis in these films lies usually in Indonesian heroism and nationalist fervour. These films were an essential part of the birth of the Indonesian film industry. A significant example is Usmar Ismail’s Darah dan doa [Blood and prayer] about the Siliwangi Division, an elite division of the Indonesian army led by Captain Sudarto. The film is considered the first Indonesian film and 30 March, the date the film first began shooting, has been declared Indonesia’s National Day of Film. Darah dan doa may be the first film about the Indonesian National Revolution, but it has certainly not been the last.

It wasn’t Ismail’s last war film either. In Enam Djam di Jogja [Six Hours in Yogyakarta] he covered the 1949 siege of Yogyakarta known as the Serangan Umum 1 Maret 1949 (“General Offensive of 1 March 1949”). The choice to depict this particular offensive is remarkable from a Dutch perspective. After Yogyakarta was taken by Dutch soldiers during Operation Crow, Indonesian freedom fighters launched an offensive in the early morning of 1 March 1949. They managed to regain control of the city, but after six hours they withdrew. On paper this seemed like a defeat, but in Indonesian popular culture this offensive is remembered as an ideological tipping point in the struggle for independence, as a soldier in the film concludes: “The news of our attack will echo through the rest of the world, until it reaches the United Nations”.

National identity

During Suharto’s New Order (1966-1968), Ismail was hailed as the “father of Indonesian cinema”, partly due to the nationalistic subjects of his work. According to Indonesian film critic Adrian Jonathan Pasaribu, the earliest post-independence films not only set an example of what Indonesia’s national cinema should be, but also established the Indonesian “us,” who fought against the imperialist “them”. The first wave of film perjuangan ended halfway through the sixties, but a new wave appeared during Suharto’s era and rolled on into the early 1990s.

Typical of the New Order film perjuangan, as film scholar Eric Sasono has observed, is the focus on heroes and heroism to affirm national identity. In Indonesian B-movies about the war of independence that appeared in the 1970s and 1980s, and even today, the Dutch are often stereotypically represented as violent, rude and immoral. Indonesians on the other hand are represented as polite, pious and typical heroes of the people.

This does deserve nuance. Representations of the Indonesian War of Independence differ, among other things, due to the control that successive Indonesian governments had over film production. Because of the political upheavals that Indonesia went through after independence, the war has been remembered in various ways. Two films made during the authoritarian Suharto era are illustrative of this. Janur Kuning [Yellow Coconut Fronds] (Alam Surawidjaja, 1980) and Serangan Fajar [Attack at Dawn] (Arifin C. Noer, 1982) portray Suharto as a national hero, but were later criticised for creating a false narrative in which Suharto’s military role during the war of independence was exaggerated.

New Indonesian films about the war

Nearly twenty years after the last film perjuangan, a new struggle film was released in 2009: Yadi Sugandi’s Merah Putih [Red and White]. Two films followed, completing the now well-known Merdeka trilogy [Freedom trilogy]. The trilogy revolves around a diverse group of Indonesians who join the army to fight against the Dutch during the war of independence. These are archetypical war films and Indonesian blockbusters, and the start of the current wave of diverse fim perjuangan.

In most cases, the Western antagonist is represented with a backstory that incorporates European narratives about the Second World War. In the Merdeka trilogy, the ruthless Dutch Colonel Raymer (loosely based on Raymond Westerling) is interned and tortured in a Japanese camp. The Dutch soldier Robert is linked to the German occupation of the Netherlands in Soegija (Garin Nugroho, 2012) and the backstory of the English Captain Wright in the animated film Battle of Surabaya (Aryanto Yuniawan, 2015) is shown by means of a flashback in which his son is seen murdered by Nazis. In different films, stereotypical images of these occupiers and their criminal behaviour in Indonesia are either confirmed, or a “myth of pure evil” is dispelled.

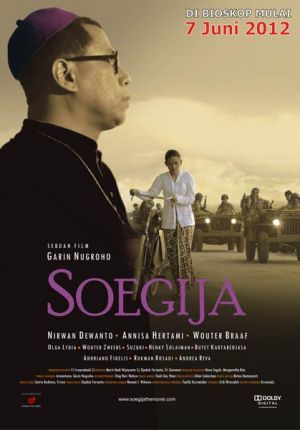

Even more important than the Dutch perpetrator are the figures of the Indonesian hero and heroine. They are not only brave and fearless, but can also have doubts about the intentions of war. Male and military heroes are overrepresented in these films, but minorities can also be found in film perjuangan. The celebrated Indonesian filmmaker Garin Nugroho, for instance, focused with his film Soegija on the first Indonesian Archbishop Albertus Soegijapranata, who bears the title National Hero of Indonesia. In doing so, Nugroho opposes the dominant discourse in which Indonesian independence heroes largely come from the same religious or military background. The film not only centres on Soegija’s nonviolent actions, but through him also gives voice to the “other” in Indonesia.

Nugroho also engages with the ubiquitous mythology of the revolutionary pemuda (“young revolutionary”) as heroes of the nation. The film critically connects the Indonesian struggle for independence with the uncontrollable violence of the pemuda, who blur the line between fighting for freedom and acting criminally. This is a discourse not commonly found in Indonesian remembrance culture. Modern Indonesian film perjuangan prove to be layered and adaptive according to new insights and contemporary concerns.

Violence

In The East, the emphasis lies on Dutch violence during the Indonesian War of Independence. This is long overdue; the Netherlands has hardly looked back at its misdeeds in Indonesia. The question of whether extreme acts of violence were perpetrated by the Dutch is a topic that is currently in the public eye in the Netherlands. In Indonesia that violence is presented as a fact and as common knowledge; Indonesian films are mainly concerned with how the Indonesians resist this violence.

Importantly, acts of violence are deeply entrenched in Indonesian war films, whether a film is strongly politically biased, propagandistic in nature, or a mainstream blockbuster. Dutch summary executions, as The East also prominently portrays, can often be found in these films. Torture scenes can even be found in Laskar Pemimpi [A Troop of Dreamers] (Monty Tiwa, 2010), which is a musical comedy about an unlikely group of independence fighters.

It is therefore more interesting to go beyond the representation of violence and look into the underlying motivations of combatants. An example might be that of the war volunteer: what motivated Indonesian and Dutch volunteers to join the war and how is it imagined in films? For instance, in The East the lead character Johan is in part driven to volunteer because of his father’s fascist past. Later in the film he reconsiders his motivations when he asks a fellow soldier “Don’t you ever question what we are actually doing here?”

Dutch films about the war

While the war is thus actively remembered in Indonesian films, the opposite can be said about the Netherlands. Feature films about the Indonesian War of Independence and Dutch actions at the time are scarce and often less explicit than Indonesian films. Gekkenbriefje [Crazy Going] (Olga Madsen, 1981), for instance, is about a teacher who does not want to refuse his conscription during the war, but tries to avoid it by being declared mentally unstable. The film is set with the independence struggle as thematic background, but takes place in the Netherlands.

Gordel van Smaragd [Tropic of Emerald] (Orlow Seunke, 1997) is set in the Dutch East Indies and Indonesia, but emphasises the Japanese occupation and Dutch victimhood during that period. The violence during the independence struggle does receive some attention, including an execution by a Dutch soldier, but it is hardly notable within the film’s broader narrative. Oeroeg (Hans Hylkema, 1993) is the best-known Dutch example of a film about soldiers during the Indonesian War of Independence and contains explicit scenes of Dutch violence. Yet the film largely revolves around the relationship between the Dutch Johan (Rik Launspach) and his native Indonesian childhood friend Oeroeg (Martin Schwab).

When Will Indonesia’s Film Industry Recover?

COVID-19 interrupted a boom for Indonesian cinema: their rate of recovery may be a bellwether for other sectors.

The East

With The East now exists a Dutch film that focuses entirely on controversial Dutch military actions during the Indonesian War of Independence. The struggle of the Dutch soldier is central to the film and the Indonesian perspective is secondary to it. Those who fight for independence remain practically invisible. We never actually see Indonesian freedom fighters in action; the Indonesian characters have little agency. An example is the role of prominent Indonesian actor Lukman Sardi, who briefly shows up as an unnamed Indonesian civilian who requires the help of the notorious Captain Raymond Westerling.

The ethical questions around Dutch soldiers’ actions on which the film reflects are less urgent in Indonesian films, as is the Dutch soldiers’ return home and their reception in the Netherlands, which The East deals with from the very first scene. The East thus opts to engage with questions circulating in the Dutch public debate. The geographical connotation of the title also affirms this perspective.

In the Dutch press, The East has been praised for its filmic qualities and ruthless representation of atrocities. At the same it has been critiqued for its lack of attention to Indonesian victims and its resemblance to Hollywood Vietnam war movies fixated on white soldiers. The film has also been released in Indonesia and it will be interesting to follow the film’s reception there. Media scholar Ariel Heryanto doubts it will lead to public protests, as the The East’s narrative supports the Indonesian nationalist agenda in practically all Indonesian films about the evil Dutch coloniser. Early Indonesian responses indeed connect the film to earlier film perjuangan and the “genocide in South Sulawesi”, but also see the Dutch viewpoint as a way of acknowledging mistakes of the past.

Positioning Indonesian and Dutch films in the same context helps to understand contrasting views on the same war. In doing so, it lays bare the differences between Indonesian and Dutch film and remembrance culture about the same war. Although previously absent, the culture of remembrance that has been so vividly present in Indonesian films for decades is now hopefully finally taking shape in the Netherlands.

This review is based on the earlier publication “De Oost in context” on 12-05-2021 in De Filmkrant (https://filmkrant.nl/artikel/de-oost-in-context/) and in print in De Filmkrant 437 (2021): 20-21.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss