I can’t offer a complete picture of the crackdown and what led to it. At this time this is simply not possible for me to do, if it ever will be. I had only views of where I went to photograph as things went completely out of control. I am weeks away from being able to somewhat analyze what happened. I have not even read any news article on the events right now, as I want to keep my memories as unfiltered as possible. So, please, do not take this as a complete account, these are just my limited personal impressions of these terrible days while working almost non-stop with very little sleep or rest. This is what I have seen, experienced and photographed. There are so many journalistic articles around by people who can do this much better than me, so I just want to give a sense of how things felt on the streets. I do try to stay away from rumor as much as I can, and if I can’t, because often rumors create perception, I will state this clearly. Please excuse any mistakes as these were very stressful days, and at the time of writing I am still very exhausted: mentally and physically.

On March 26 maybe 20-30,000 Red Shirts gathered at Sanam Luang, to march in blistering heat to Government House. The highlight of this march was when the Red Shirts brought their own heavy cranes to remove sand filled containers the government placed in their way to stop the protesters from encircling Government House. Quickly the containers were removed; two of them were lifted into the klong [canal] that runs opposite the main gate.

[Click on the images for full-size versions.]

A stage was built, speeches held. There were no incidents of violence, no attempts to enter the Government House compound. The usual market appeared – massage stalls, stalls selling Red Shirt paraphernalia, and food stalls. Police officers mingled with protesters. Most officers I asked, expressed their support for the Red Shirts, a very common statement was: “I am neutral, but my heart is red.” Many of these officers also said that their families are with the protesters. Some even changed into Red Shirts after their shift ended (I will not show photos of this right now, as I do not want to cause disciplinary actions against these officers).

On March 27 Thaksin Shinawatra had his first live video link to the protesters. This was a radical departure from his previous phone-ins. No more fluffy “I miss you, do you miss me” phrases. This was a radical attack at Privy Council president General Prem Tinsulanonda, and other members of the Privy Council, for orchestrating the 2006 military coup. He demanded the democratisation of Thailand. The crowd cheered.

All speeches on the stage revolved around the term “Amartayatipatai” – the most suitable definition may be “the rule of the traditional elites”, attacking the Democrat government, the military, and members of the Privy Council.

The Government had counted on the end of the protests on March 29 as the Red Cross fair was to begin the day after. But the protesters remained. The media speculated on decreasing mass support, but every night ten of thousands gathered at Government House. Not just upcountry people attended, but increasingly large numbers of middle class Bangkokians too. I was told that even members of the October 14 network, which has been part of the yellow-shirted People’s Alliance for Democracy (PAD), have visited the Red Shirts behind the stage, showing signs of switching sides.

On March 30 in the morning there were rumors that police might disperse the protests. There was a small build up by police. I was told that this was a ruse by the Government to keep most of the protesters at their location at Government House, so that Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva could attend a meeting in the nearby United Nations building without protesters harassing him.

In some provinces Red Shirt protesters had occupied City Halls to support the Red Shirt protests in Bangkok.

In Bangkok, protest leaders and guards tried to keep the protest peaceful. A few undercover agents were caught trying to sneak in (mostly because they carried guns which were found during searches at the entrances), but they were led behind the stage and handed over to police. A few overzealous protesters were reported to have attacked a women and one provincial governor who wore yellow shirts, but Red Shirt guards protected them.

On the afternoon of March 30 PAD made their presence known at a small protest in front of the National Police Headquarters opposite Central World. About 500 to 1000 people attended, a few dozen of their guards were present. Rumors made the rounds that after their protest they would attack the taxi community radio station at Vibhavadi Soi 3. Hundreds of taxi drivers gathered there. Nothing happened though.

I was getting very worried when Red Shirt leaders announced their D-day, and that they would march to Gen Prem’s house. How would the military react? Already PAD members told me that the attacks against Gen. Prem in their view are equal to lese majeste, and that they could not tolerate this. I feared that the Red Shirts might have overshot their mark, that they overestimated their support, and underestimated the anger of the more radical parts of the military. My fears only increased when Jakrapop Penkair explained that the Red Shirts had decided to stay at the protest site at Government House indefinitely.

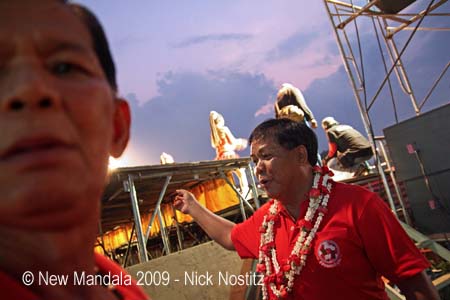

On April 4 I went to Udon Thani. I had a job for a Western news network as a fixer. On that day the Udon Lovers organised a large fundraiser on the occasion of the 3-year anniversary of their community radio station. A stage was built on the field in front of the station, and 430 round tables for a Chinese dinner were set up. Each table cost 2000 baht, seating ten. The tables were sold out in advance.

I was surprised to see Dr. Weng and Wiphuthalang Phattanaphumthai, two of the top Red Shirt leaders, arriving. Dr. Weng spoke on the radio, and was interviews by the news team. He soon departed for meetings in a neighboring province.

People began arriving at the fund raiser at sunset. About 5000 people attended. There were singers on the stage, speeches were held. Thaksin phoned in. People were convinced that they would win. Kwanchai Paipanna announced that they have hired 50 busses for the journey to Bangkok, that 2500 protesters would be able to go to Bangkok. People made donations.

The dinner was cut short when a thunderstorm arrived.

The next day, we went to a village with active Red Shirt support. In the village sala [pavilion] many villagers with Red Shirts waited for the foreign media team. The team went to one of the villager’s homes, and interviewed him about his life, and why he supports the Red Shirt movement and Thaksin. When we went for lunch with Kwanchai Paipanna, the owner of the restaurant handed him an envelope containing donations to the Udon Lovers collected by the staff of the restaurant.

Back in Bangkok, preparations were made for the D-day. On April 7 there was news that a new group of Prem supporters had gathered in front of Prem’s residence at Thewet. They wore light blue neckerchiefs, and called themselves a spontaneously founded citizens’ group – the “Glum Rak Pandin Goed” (The Group that Loves their Land of Birth). Most of the few dozen people had difficulties remembering the group’s name, and garbled it when I asked them. They walked in and out of the army installation next to Prem’s residence, mingled with the soldiers there. I met many PAD guards who I knew from the government house occupation of last year, and who remembered me as well.

On April 8 the march to Prem’s residence began. At first it was announced that people would meet at 10 am, and the march would start in the early afternoon. The march though began much earlier, and I arrived just in time when Red Shirts began forming up their lines in Sri Ayutthaya Road near Royal Plaza. Police told me that they sent the blue neckerchief guys home at 7 am, by that time there were 300 odd.

A massive crowd marched to Prem’s compound, and managed to surround it without any violence. After a while I went home, and returned in the evening. I won’t dare to guess the number, organizers said 300,000, police said more than 100,000 (I do give more credence to the police number though – they do make their assessments according to satellite images and per square meter occupation). It nevertheless was the biggest mass protest I have seen during the last 3 and a half years of political turmoil in Thailand, dwarfing every single PAD protest march. The whole of Sri Ayutthaya Road was packed with people, huge crowds at Royal Plaza, and the whole of the roads surrounding Government House. There were multiple mobile stages, with small street bands playing fast Isaarn Rock to which people danced on the streets.

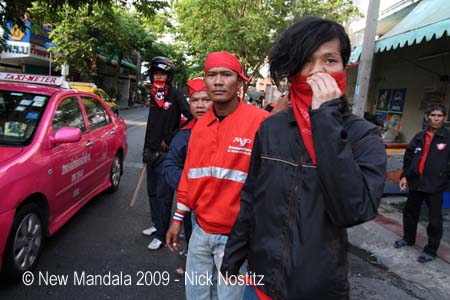

The day after, on April 9, the road blockades by the Red Shirts began. At first there were mobile rallies at different key locations. I went to the rally at Democrat Party headquarters, which was led by Kwanchai Paipanna and the Udon Lovers.

News came that taxi drivers spontaneously, from what I was told, blocked several roads. I went first to the Rama IV/Rajawithi intersection, then to Victory Monument. So far, this was still within the limits of what I would describe as civil disobedience and nonviolent protest.

Nevertheless, there were undertones of extreme tension. When police appeared from the expressway, the mood of the protesters became extremely agitated. One mistake by the government, and I felt that the mood could swing. Police retreated.

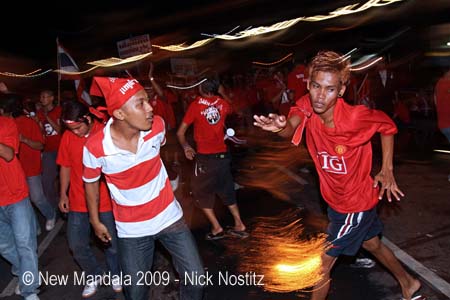

At 6 pm a massive thunderstorm came, and soon after I went home. By night I returned. The atmosphere was amazing, and very intense. I photographed a group of mostly young people who had a small cart with a music system, playing heavy bass laden tunes, dancing wildly, reminding me of African tribal dances. Water was splashed around. Speeches were held from a mobile stage. I remember having seen Jakrapop Penkair on the stage.

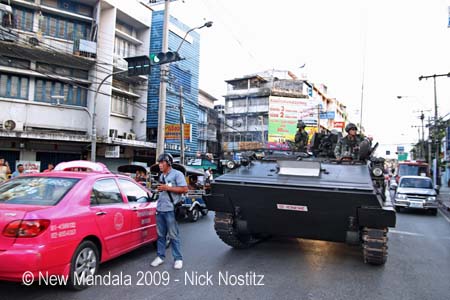

On my way home I photographed a combined police/army roadblock at an underground station near my house.

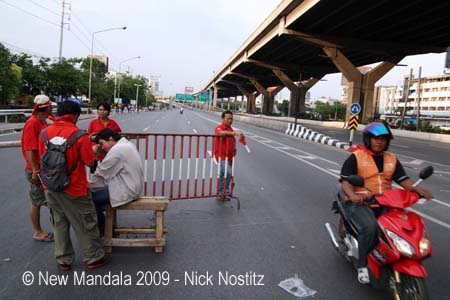

The next day I went to the Suthisarn/Vibhavadi Rangsit Road blockade. This was for me the most fascinating blockade. The whole of Vibhavadi Rangsit Road was empty. At the blockade there were many local residents with their families mixed with protesters from other parts of town, and a small mobile stage under the expressway.

That night I decided to follow the protesters to Pattaya, where Abhsit’s car was attacked by Red Shirt protesters on April 7. From what I could make out from Bangkok the atmosphere seemed to be heating up there. Friends who were there already told me that Blue Shirts were present, and that there was a brief clash between Red Shirts and Blue Shirts, where some Red Shirts were injured by stones thrown at them. I had already once tried to find out more about the so called Blue Shirts, rumored to be a group set up by Newin, when they were seen at Suvarnabhumi Airport during the beginning of this round of protests, but my search was fruitless when I drove there.

On the road from Bangkok to Pattaya were hundreds of cars with Red Shirts joining the protests there. Many taxis, and pickup trucks loaded with Red Shirts. There were several road blocks slowing the traffic down. On the outskirts of Pattaya there was a roadblock where a few Red Shirt cars were briefly held back, but soon allowed to continue.

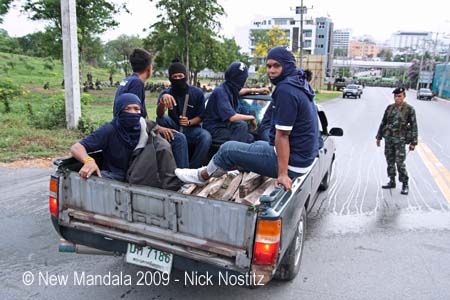

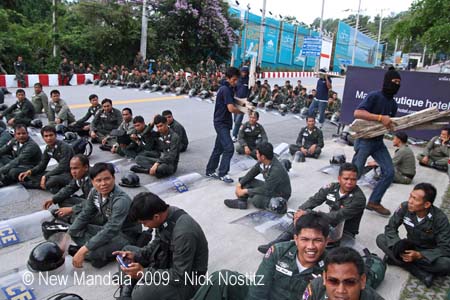

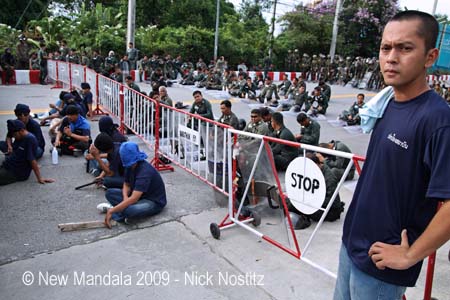

At about 6 am I went to the security zone around the Royal Cliff Hotel. On the bottom of the hill there was a roadblock by the security forces, the first line was the Border Patrol Police (BPP), the second line was the Army. I was at the Tourist Police station halfway up the hill when suddenly several hundred Blue Shirts walked out from within the security zone. One blue pickup truck with Blue Shirts sitting in the open back appeared transporting wooden clubs. I took photos. The Blue Shirts objected, but I did not care. A soldier told them to drive further down the road. I followed on foot. At the bottom of the hill, several dozen Blue Shirts hung out at the road block. Several Blue Shirts carried the pieces of wood through the Army and the BPP lines, and distributed them to their friends, who lined up in front of the BPP. I recognized some Blue Shirts as PAD guards, and they also remembered me from the Government House occupation. Others of the Blue Shirts very much looked like soldiers (I was told later on that they were Navy personnel from Satthahip).

Soon a large group of Red Shirts appeared with a mobile stage. At first there was a loudspeaker duel between Red Shirts and Blue Shirts, soon the two groups faced each other from a distance of less than 200 meters. Nirmal Ghosh called me, he was at a different access road, and told me that a brief clash between Blue and Red Shirts had already happened there, but that when a small bomb was thrown, Blue Shirts retreated behind military lines. Where I was standing a clash was beginning to build itself up. More than 1000 Red Shirts were facing maybe 300 Blue Shirts. At the last moment, when the groups were only 50 meters away from each other, negotiations were held, and soon after the Red Shirts left.

I walked up the hill. There was a large group of Red Shirts in front of the Hotel where the ASEAN Summit was to be held. Apparently one or two Red Shirts were shot by Blue Shirts, but I am still confused about when exactly that happened, during the brief clash, or during the previous night. Red Shirt leader Arisamun Pongruengrong demanded that the government deliver the responsible Blue Shirts to justice. He held a press conference inside the entry area of the conference building of the Hotel. Several Red Shirts have shown off a sack of blue shirts that they found during their approach to the Hotel. After a lull of about one or two hours, suddenly Red Shirts walked into the grounds directly in front of the Hotel doors. Army and police appeared to be lost for an answer. Red Shirts stood at the front doors, and suddenly began pushing. One large glass window suddenly broke, and Red Shirts stood inside the Hotel. I was completely astounded, and let myself be carried with the flow of protesters who streamed into the hotel like an overflowing river. There were bewildered journalists, delegates and observers from many Asian countries watching on. In between were tourists in swimming trunks. Some Red Shirts stood next to them and snapped pictures with their mobile phones, and the tourists took their images. There was no violence, it was just plain bizarre and surreal. Soldiers ran to protect the entry of the main hotel building; Red Shirts ignored them, walked around and entered through a side entrance, searching for Abhisit. In general, the protesters were noisy, but very well behaved.

After half an hour the Red Shirts simply left the Hotel. I photographed one young soldier who had collapsed from the heat and dehydration. Army medics took care of him, and an old lady with a Red Shirt massaged him. The Red Shirts retreated to their protest site behind Big C in North Pattaya as Abhisit has declared emergency rule over Chonburi Province and Pattaya, and then they decided to return to Bangkok.

On April 12, I got the news that Arisamun had been arrested. Red Shirts demanded his release, and protested in front of the court building in Ratchada. The same afternoon, Abhsit declared at the Ministry of Interior, Emergency Rule over Bangkok and several surrounding provinces. A very confusing situation developed. It was reported that enraged Red Shirts attacked Abhsit’s car, and that his driver fired warning shots into the air, after which he was beaten up by Red Shirts. Red Shirts complained of several injured when Abhsit’s car crashed into them, and some claimed that some of the hurt protesters were dragged by security forces into the building.

When I arrived, Red Shirts remained at the gates and in the grounds, there were soldiers as well, some of them armed with M-16s. It was a tense situation. Things clearly began to turn bad. Red Shirts searched the buildings for their injured (none were found). Suddenly a car seemed to try to escape, followed by angry red Shirts. I went after, and found that the car crashed through a fence and into a taxi, and was stuck halfway in the compound and the foot path. In the car were two men stuck, the driver and Democrat Secretary-General Nipon Prombhand. Red Shirt guards surrounded the car, trying to hold the angry crowd back. After taking some images, I pushed a few too aggressive Red Shirts away, and shouted at them that they should not behave like animals. The guards applauded me, and so did several other Red Shirts that tried to keep the situation from getting any more out of hand than it already was. Not long after, Red Shirt guards managed to get the two injured men out of the car, and sent them off to hospital safely.

It seemed that a point of no return had been reached, and in the early hours of the following day the crackdown began.

On Monday April 13, my wife woke me up at 4 am in the morning, at the same time a friend rang me. It had begun, they said, in Din Daeng. I arrived at Samliem Din Daeng, the corner of DinDaeng Rd. and Ratchaprarop Rd., shortly before 5 am. It was dark, and in the close distance single shots were being fired, and there were brief bursts of automatic gunfire. There were ambulances, angry Red Shirt protesters, and a few Thai photo journalists. As I walked carefully towards the fighting, Red Shirts were running towards me, away from the sound of bursts of automatic rifles. They shouted that the Army was coming. I ran with them, my bullet proof vest, the heat and plain fear slowed me down. But it calmed down again.

Agitated Red Shirts told me of people having been killed, and dragged by soldiers into lorries. I have no way of verifying this. This was obviously not a situation where I could cross the lines and make polite inquiries. I waited. Black smoke wafted from burning tires. Young Red Shirts prepared for the assault with petrol bombs in their hands. One of them tried to incinerate a few tires with a petrol bomb, but the fuel splashed over his legs, and he was briefly on fire until his friends could put it out.

By daybreak suddenly the intensity of the shooting increased, and the Red Shirts ran away. I hid under a tree, heard a few gun shots, and a few meters above me a bullet went with a very ugly noise through the leaves of the tree. I ducked into a side alley, to let the Army overrun me, and then to come out again when things were safer. Two Red Shirts were hiding in the Soi as well. They pulled their shirts off, and local residents hid the two in their house. When soldiers appeared in the Soi, I held my camera up, and said that I was a journalist. No questions were asked, and with relief I took images of the tense soldiers. The soldiers appeared not to move any further. More media arrived; some came from behind the soldiers, some from their homes.

I realized with panic that my camera has given up. I could not make it work. The culmination of more than three years intense work, and exactly that moment my camera had to break. And that on the only Thai holiday where almost every shop is closed. Both Nirmal Ghosh and Jonathan Head offered me to loan me their cameras (for which I am eternally grateful!) when I called them and told them of my luck. As things seemed to stay calm, I decided that I would first go home and see if my photos from the morning were saved, and to see if I could find a camera shop.

At shop opening time I went to the shops opposite Central Lard Prao, and found one shop that was open, and where I could find the same camera I have got used to, a Canon Eos 450 D – the cheapest 12 megapixel camera. I am not rich, and it did hurt having to buy a new camera, but at least I could continue working.

I went back to Din Daeng. Things were still the same. The Army was in the same position, and nothing happened during the 3 hours I was away.

I sat next to a young Corporal. We talked about what happened. He was not happy to be there. He was from Isaarn, and had also relatives among the Red Shirt protesters, naturally. But a soldier has to follow orders.

Red Shirts were at Victory Monument and slowly closed in on the army from both Ratchaprarop Rd and from the direction of Victory Monument . Maybe 200 meters away from the army they stopped. One man walked over to the army with roses. An International Red Cross official was there trying to negotiate between the Army and protesters.

Protesters became agitated, began burning tires. Photographers photographed. The army drove two water thrower in. On Rachaprarop Rd. a bus was set ablaze by Red Shirts, a gas tank placed in front of the bus. The soldiers extinguished the fire with their water thrower and began to move in, shooting their rifles with single shot in the air. The noise was tremendous. This time the assault seemed to be more orderly and disciplined than the one in the early morning hours. This time I could not see soldiers firing straight, but of course I could just barely see what was next to me. As the Red Shirts dispersed, I walked back to the intersection. A bus suddenly appeared on the overhead bridge driving towards soldiers there. I saw the soldiers firing on the bus, and the bus crashing on the rails of the bridge. Fortunately it did not run over the railing and the soldiers stationed under the bridge. I feared that we might have had the first casualty that I could see, but when I walked later to the bus, I saw it riddled with bullet holes but no blood. The entire front window had fallen out and was on the tarmac in front of the bus, the glass riddled with bullet holes. Somebody told me that he saw a person jumping out of the bus just before the soldiers fired.

The assault by the army went the same way, soldiers walking orderly, firing their rifles in the air in single shot, and securing side alleys. I photographed one bus whose windows had bullet holes, most likely from automatic rifles shot from the direction of the soldiers. They pushed the Red Shirt protesters off Victory Monument. I photographed how a few injured Red Shirts were taken away roughly by soldiers. One of them I heard saying: “I am just an old man, I haven’t done anything to anybody”. I cared not for the soldier telling me not to take photos.

Things stayed calm. On the Pahon Yothin corner a few tires were set ablaze. The black smoke with Victory Monument in the background made for a dramatic frame. I guess every photographer on the scene captured it.

I walked across to Rajawithi Hospital. A bus was aflame – another dramatic shot. A few Red Shirts were there, and have shown me bullet shells they had collected.

After a while I went home; to take a rest, and to store my images on the computer. In the early afternoon I went back out again, I wanted to go near the Government House area. Just as I left my house, Thilo Thielke, the “Spiegel” correspondent, called me, and told me that I should consider myself under assignment. At least now the heavy financial blow of having to buy a new camera would not result in any more difficulties with my bank than I have already, and I might even be able not to, as usual, operate at a loss.

When I arrived at Yommarat, I asked some residents in a small side alley if I could store my motorcycle in front of their house to keep it safe. When I came back later to pick up my motorcycle, these very nice people had even covered it with a straw mat to protect it against the sun. They gave me cold water to drink, and asked me what was happening, and expressed strong disappointment at the violent crackdown.

I went over to the Rama 6 – Petchaburi Raod intersection, took photos of a burning bus, and of one young tattooed Red Shirt protester. He screamed in the direction of the soldiers stationed at the Sri Ayutthaya intersection: “Why do you kill us! I am Thai as well! I may be poor, but I also have my beliefs!”

From Petchaburi Road a mobile stage and a larger group of Red Shirts approached. Suddenly there were a few cracking sounds, a commotion, and soon waiting ambulances drove past me in the direction of the group of Red Shirts. Several Red Shirts that passed by said that PAD members had shot at them out of Petchaburi Soi 5. I walked over there, and managed to photograph one of the injured. He was screaming; a bullet lodged in his leg.

When the ambulances left, fire fighters extinguished a few burning structures inside the Soi. I decided to leave, as most Red Shirts had already left the scene, and I did not want to be caught out alone by roaming armed local residents/PAD. I picked up my motorcycle and parked it somewhere closer to the protest site in case of a military approach.

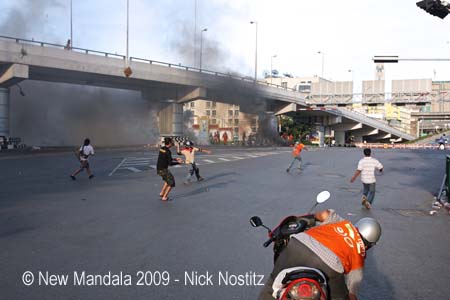

I briefly went to the Red Shirt stage, I met Prateep Ungsongtham Hata, who led a group of Red Shirts with flowers to the military lines. I wanted to follow, but lost sight of the group. From the direction of the railway lines at the express way entry a huge wall of black smoke rose into the sky. Another bus was set ablaze by enraged Red Shirts. Things then began to completely get out of hand. A fire truck arrived, trying to extinguish the fire. Angry Red Shirts chased the firefighters away. Suddenly youths from the slums along the railway lines attacked the Red Shirts. They fired guns and threw stones at the Red Shirts positioned at the overhead bridge, Red Shirts fought back with stones and petrol bombs, set one house in the slum on fire. Later I was told by both Red Shirts and intelligence officers that many of these residents of the slums were also PAD supporters, and that this was not their first confrontation. The fighting went back and forth, and as it became dark soon I decided that I did not want to remain there, I was too frightened. I am not a combat photographer, I am a father and husband, and nothing is worth such a risk.

I picked up my motorcycle just as the Army began moving in to Yommarat, and parked it in a side alley close to Nang Loen intersection, several hundred meters closer to the stage area.

I went behind the Red Shirt stage, I wanted to see the mood there. I sat with some who were preparing a press conference that Chaturon Chaisaeng was to hold later in the Royal Hotel. Several people argued. There were signs of desperation and collapse. Veera Musikapong came from the stage. He had a flower garland on his head, and joss sticks in his hand. He went to the small area reserved for protest leaders, and prayed. I went in, and photographed him. He was very quiet, and asked me if I would like to have dinner with him.

Jatuporn came as well, and an academic whose name I can’t remember. I asked how things will proceed now. They said that there is no control anymore, sad and resigned to fate: “What will happen, will happen”. I excused myself, and continued working.

I drove my motorcycle out of the Government House area. I did not want to risk having my motorcycle there in case the Army would close off the area before their final assault. A friend, an intelligence officer, told me the still open exit routes. I had to drive my motorcycle through the protesters and out of Makhawan bridge to Rajadamnern. This route was still clear. On Rajadamnern were a few burned busses. I sat a while with my friend. We heard the sounds of gunshots from the direction of Nang Loen.

We then went behind Metropolitan Police headquarters. There was a small crowd of extremely angry Red Shirts. They attacked every vehicle of the Thai media, angry by the not exactly unbiased reporting. Unfortunately, what many of them do not understand, is that Thai journalists are as divided over the political situation as the general Thai population, and many Thai journalists do not agree with the PAD or government policy. The result of these attacks was that most Thai journalists did not dare anymore to go close to the Red Shirts, and remained with the Army, even as Red Shirt leaders asked the protesters not to attack them. Part of the problem of course is that also many speeches on the stage condemned Thai media for being too partial towards the PAD. This is not too untrue, but unfortunately it results in attacks against the media. Right now only foreign journalists can safely work with Red Shirts. This is a huge problem for the future. Very few foreign journalists are fluent enough in Thai to directly speak in Thai, and too few Red Shirts speak English well enough. Also, Red Shirts expect too much from the foreign media. The media business is a business, and a story is only hot while it is big enough. When Thai journalists cannot work with Red Shirts, there is very little chance that their views will be heard in the traditional media outlets. It is more than important though that Red Shirts have a voice in the media.

With all this in mind, I decided to join the press conference. Along the way at Rajadamnern I passed Kaosarn Rdoad where many young Thais and tourists partied Songkran-style. I had to dodge groups throwing water.

The uniformed door keepers at the Hotel were asking me what was going on. They were distraught by what they had seen on TV that day. Inside were a few journalists waiting for Jaturon. When he came there were only 7 or 8 journalists at this press conference. I could not bear staying long; this was just a too sad affair.

I met up again with my intelligence officer friend. The following hours I didn’t do much. We were mainly expecting the final assault on the protest site by the Army. Nobody had any real information, speculation and rumors was all there was. None of my friends from the police was given any information whatsoever; police was kept almost completely out of the loop. First I was behind the Metropolitan Police Headquarters on Pitsanulok Road. This was one of the two routes out of the area where Red Shirts could leave the protest site. Police, who were otherwise not involved in the crackdown, kept security there. At the time 4000 protesters were estimated to have remained at the site. Small groups of protesters passed by, asking if it was safe to leave from there, fearing the PAD were waiting for them.

I decided to stay, in case the final assault came, and the Army would cordon off the whole area, and I feared I could not get in anymore if I left. I settled in front of Metropolitan Police headquarters. A slightly surreal incident was when suddenly a girl in hot pants and high heels walked by the police and journalists sitting around there. A cart drove by selling essentials. I bought a pack of cigarettes and a few cold towels to clean some of the accumulated grime and sweat off me. I met up with a colleague who had walked through the area of fighting between local residents/PAD and Red Shirts. He told me how he had seen people on motorcycles suspected to be Red Shirts having been badly beaten up, and how one of those local residents/PAD had pointed a gun at him from short range with what he thought was the clear intent to kill him. Fortunately one of the other thugs took the gun away from his friend. After hearing this I was very glad to have decided not to take pictures there. I managed to sleep about two hours in one of the half torn down structures left over from the Red Cross Fair.

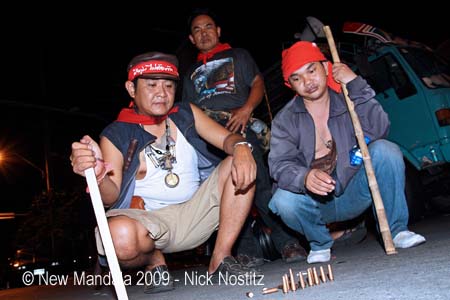

At about 4 or 5 am I went to Pitsanulok Road at the Nang Loen intersection. There were no sounds of gunshots anymore, and the fighting seemed to have dropped off. I spoke with several Red Shirt guards who told me harrowing tales of the battles, of how they have seen friends dragged away and beaten to death, and how they could not reach the corpses before they were snatched away. I photographed some of them with bullet shells they collected, both AK-47 and M-16 ammo.

By sunrise no assault by the Army came, and I went home. I caught two and a half hours sleep. At ten in the morning I went back to the protest site. I entered from Sri Ayutthaya Rd., parked my motorcycle in the Metropolitan Police headquarters, and walked into the Red Shirt-held area from Royal Plaza. About 2000 protesters remained at the site. Back at Pitsanulok Road I met up with Nirmal Ghosh and several other colleagues. Our plan was to stay there at the frontlines, and when the final assault began, to duck into one of the alleys and stay with local residents, and then to slip out and get in with the Army. The Red Shirt guards were resigned to what was to come. I took a photo of one Red Shirt who was caught by a small mob of PAD not long before that morning, and whose back had a deep gash from a machete. His hand and head were bandaged.

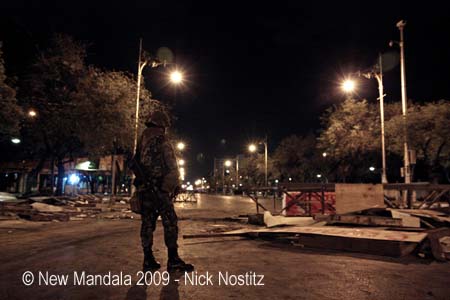

Another bus was set ablaze and one gas tank, which then burned out with large flames. A few residents extinguished the fire in the tank. In the alley where we planned to stay the locals had sympathies for the Red Shirts, but asked them to leave the alley for the safety of the residents. The Red Shirts complied, one with a portable loudspeaker appeared, and asked all Red Shirt guards remaining in the area to move behind their barricades at the Nang Loen intersection. He said that all Red Shirts that remained would be considered “third hands” and not be accepted inside anymore. Very soon soldiers appeared in the Soi. Local residents asked the Army to leave as well, for the safety of their houses. The soldiers formed a road block deeper in the Soi. I saw a small squad moving into a side alley.

Suddenly news came that Veera Musikapong had been the stage to call off the protests, and had announced their surrender. I was extremely relieved, as an army assault would have been very ugly. There were a few tense moments when a small squad appeared out of a small alley near the Red Shirt barricades, but after brief negotiations the Red Shirts stayed calm, and the squad only secured Pitsanulok Road up to Yommarat.

I walked around the protest site. The Army stayed out. Protesters began to abandon the area. I spoke with some that were nearly crying. Many were flicking a resilient V sign to me. One old Red Shirt slit open water bottles with a cutter, mumbling to himself: “This is our water, these soldiers will not drink our water.”

At the Royal Plaza exit Dr. Weng stood on a loudspeaker wagon, and asked the soldiers to retreat as they were leaving anyhow. Soldiers were searching leaving Red Shirts, and recorded their IDs. Still protesters flicked the V sign to me. On Royal Plaza Veera Musikapong and Nattawut Saikua stood on the back of a pickup truck, surrounded by commando police. Nattawut said: “We surrendered to save lives. We will not give up and will continue fighting for democracy.” Soon they were led to Metropolitan Police Headquarters, and also soon Dr. Weng followed the same route. When he was led up the stairs he made the V sign to the journalists.

I went home.

In the afternoon I got another call. The caller said that on Prachtipatai Rd. near Democracy Monument a small gathering of Red Shirts was dispersed, and one protester was shot dead (later it turned out that this protester was just injured). Several hundred protesters had retreated to Sanam Luang, and gathered there. It was very emotional. People shouted their frustrations, some cried. They handed out computer print outs of protesters they assumed to be dead. Police was present, but soon retreated further away, not to aggravate the situation.

There were a few western journalists, and Pravit from The Nation. One Thai photo journalist was there, he was very scared of being attacked. The sad part there was that he has certain sympathies for the political aims of the Red Shirts, but in this situation the protesters did not differentiate much between individual journalists anymore – Thai journalists were their enemy, western journalists were welcome. Later the famous Muad Jeap, who wrote the book Thaksin, where are you? appeared. She was crying, and hugged a protester. Soon after I went home, completely exhausted.

Where are we now?

The polarisation of Thai society has not been solved; it is, after the crackdown, starker than ever. The Red Shirt movement has been crushed, its leaders either in jail, or on the run in the underground. The ordinary supporters are very bitter over the crackdown, and so angry over what they see as completely biased Thai media reporting that Thai journalists cannot safely approach Red Shirts anymore. The movement is demonised by the media and the government. Their websites and community radio stations have been closed.

Red Shirts are convinced that a number of their members have been killed (and I have strong suspicions that they are not too wrong in this assessment, but have no evidence or proof whatsoever). The government has to organise an official and neutral inquiry. And it has to stop lying that only fake bullets were used, and only fired into the air. I have photos of bullet holes, where I have seen soldiers firing. The bullet that passed a few meters above my head in the leaves of a tree under which I was hiding in the early hours at Din Daeng was not a fake bullet or sprung out of my imagination, and given the distance and angle of the shooter from the military lines, the difference of the elevation of the muzzle was not more than a few centimeters. This was clearly a shot fired in the direction of the crowd and not into the sky. I have seen soldiers refilling their magazines with copperhead bullets. They were not fake bullets.

The Red Shirts complain about double standards. They are not too wrong about this either. When the PAD occupied Government House, Abhisit personally interfered on the ground at Makhawan Bridge in the court ordered police dispersal. No action was taken when Samak declared Emergency Rule, and when the airports were occupied, no action whatsoever was taken by the Army.

There is no doubt that things went completely wrong, and also the Red Shirt leadership has to take responsibility for much that happened. When they declared their D-Day, and their indefinite protest at Government House, they overestimated their abilities, they also overestimated their ability to control the deep-seated anger and sense of injustice among their supporters. I refuse, however, to accept the present tone of the Thai media that demonises the Red Shirts. Much of the escalation is the responsibility of the Government. How, for example can it happen that PAD guards and Navy personnel can appear disguised as “Blue Shirts”, who have collaborated with the security forces, as is proven beyond doubt, to engage in clashes with Red Shirts? That was not the decision of a local commander – this has been a top level political decision.

This is reminiscent of the dirty games and strategies of the 1970s, of extreme right wing militias, such as Navapol and Kratingdaeng, who with high level government and military support acted as agent provocateurs. Are we really back in this dark era of Thailand’s history? Have we not learned one thing?

I very much doubt that the crackdown has persuaded the Red Shirt supporters to suddenly support Prime Minister Abhisit and his government. There are indications that some groups will continue from the underground, and a low level insurgency might result. I wonder very much what can be done to begin reconciliation, and if the government is even willing to take the necessary steps beyond statements of intent that I suspect are nothing but spin. There have to be substantial negotiations, and a compromise. But that entails that some of the demands of the Red Shirts have to be met. The Red Shirts have to be heard, much of what they say is valid criticism, and a contribution to progress in Thailand. To accuse them of simply being tools of Thaksin to get his wealth back, is an extremely dangerous misjudgment based on ideology and not on fact.

There still are leaders that are open to negotiation. But the window of opportunity is short. If this movement goes even partially into the underground, than it will take a long time and a lot of blood before another chance might appear.

And to fight such an underground movement, the government will have to use strategies and tactics that will not be combined with human rights and due process of the law. Do we want such a Thailand, or can a Thailand be built in which difference of opinion, even when it crosses the boundaries of state ideology at times, can be accepted and not result in people getting killed?

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss