Shortly after his re-election in May 2019, President Joko Widodo (Jokowi) delivered his Vision of Indonesia speech, in which he pledged “zero tolerance against those who undermine Pancasila”, the pluralist state ideology. The President then instructed the Coordinating Minister for Politics, Law and Security, Mahfud MD, to initiate more “serious efforts” at curbing the spread of radical ideologies. A range of polices has been systematically implemented since, from weeding out radicalism in public service—including through online surveillance mechanism—to the proscription and prosecution of certain Islamist organisations.

One Islamist group that has borne the brunt of the growing state repression is the Islamic Defenders Front (FPI), an infamous organisation that has graduated from morality racketeering to becoming the country’s most formidable opposition movement. The Jokowi government officially banned FPI on 31 December 2020, citing as reasons its past involvement in vigilantism and hate campaigns against minorities, but also its purported link to terrorism and the more procedural reason of lapsed registration. The banning was immediately followed by more arrests of FPI’s prominent leaders and the freezing of its assets. This is qualitatively different from the disbandment of Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia (HTI) in 2017: thus far no HTI leaders have been prosecuted and most of its assets and activities have remained intact, sans the flag and symbol.

What are the consequences of the hard clampdown on Islamist groups? Has it achieved its stated goal of defending pluralism? I argue that the costs of repression far outweigh its benefits. While the crackdown seems effective in undercutting the capacity of Islamists to mobilise, it can lead to damaging outcomes. First, the policy is buttressed by excessive use of force against Islamist and other opposition activists. Second, the cost of repression directly impacts public health as disillusioned Islamist groups contribute to conspiracy theories rejecting COVID-19 vaccines. Third, dissolving one or two hardline groups does not necessarily address—and may in fact divert attention from—the complex causes of discrimination against minority groups.

FPI: from the fringe to centre stage and back again?

Born on the fringes of Islamic activism in 1998, FPI later gained prominence among Indonesian Muslims, especially after playing a leading role in the unprecedented 2016 mobilisation which toppled the Chinese-Cristian governor of Jakarta, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (Ahok), who was accused of blasphemy. After the anti-Ahok rallies (also known as “212” movement after the date of the mammoth protest), FPI and its partners used their newfound clout to assist Jokowi’s rival, Prabowo Subianto, in the highly polarised 2019 presidential campaign.

The alarming rise of Islamist influence in national politics prompted the government to contain their power, for instance by investigating and arresting leaders of the 212 Movement. FPI supreme leader Habib Rizieq Shihab, who was under investigation for his alleged involvement in a porn scandal and also facing defamation charges, decided to flee the country in April 2017 and remained in for Saudi Arabia for three years.

His homecoming celebration perfectly captured his new status as a beloved spiritual leader of the opposition. Upon his return on 10 November 2020, he received a hero’s welcome with tens of thousands of supporters coming to greet him at the airport. Prominent politicians like the Jakarta governor Anies Baswedan also went to visit him; other politicians seeking to curry favour with Islamist constituencies attended his daughter’s wedding shortly after his return. On 1 December, the police summoned Rizieq for breaching public health protocols, but he refused to comply. On 7 December, a police intelligence team tasked with tailing Rizieq shot dead six of his body guards in a dramatic car chase. Four of those have been classified as extrajudicial killing by a National Human Rights Commission investigation.

The incident was swiftly followed by the prosecution of Rizieq and at least seven other FPI figures. In April 2021, FPI secretary general Munarman was arrested on dubious accusations that link FPI to the terrorist group Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS). Munarman retorted that the “terrorisation” of FPI is a ploy to legitimise the killing of FPI guards. His statement harks back to pent-up grievances related to police abuse of Muslim terror suspects. In June 2021, Rizieq was sentenced to 4 years and 8 months jail for violating public health restrictions and spreading false news by lying about his positive Covid test.

The sweeping crackdown on FPI indicated the government’s concerns over Rizieq’s skyrocketing political stature. Many pluralist and liberal groups are similarly worried about Islamist encroachment into the mainstream political arena, which explains their muted response even as the crackdown turned violent.

Public opinion polls indicate high approval for Jokowi’s anti-FPI policy. Fealy and White argue that the limited criticism of FPI’s banning means the government has “effectively removed its most potent Islamist opponent and won public plaudits for doing so”, suggesting that FPI might have slid back to the fringes of Muslim society. The authors also note that such an outcome has made other Islamist groups “wary of crossing the government”. While the clampdown seems effective in the short term, I question its broader implications not only in terms of democracy and pluralism promotion but also its adverse consequences for public health.

Effective but at what cost?

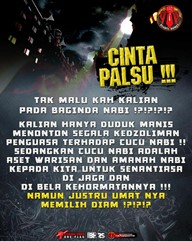

On the one hand, the repression is largely effective in weakening FPI’s mobilising capacity. With Rizieq locked up, FPI’s re-incarnation, called the Islamic Brotherhood Front (also FPI), is struggling to revive its organisational structures. FPI has also failed to draw large crowds to rallies, to the extent that it publicly rebuked its own supporters for failing to show up en masse during Rizieq’s trials. FPI-affiliated channels on Telegram circulated online memes reprimanding his supporters. One poster entitled Fake Love asked his supporters: “how could you just sit and watch all the abuse being inflicted by the regime upon the Prophet’s grandson” (i.e. Habib Rizieq). Another meme labels those who abandoned the struggle as “losers”.

When FPI called on its supporters to swarm in front of Jakarta’s High Court for Rizieq’s verdict announcement on 24 June, some followers responded on FPI’s social media platform by frivolously apologising for their absence as they lived outside Jakarta—something that hadn’t prevented them from attending anti-Ahok rallies in 2016. Others said that they had to lay low after being chased by the police cyber-patrol squad for posting anti-government contents. Still others feared imprisonment—over 400 protesters at Rizieq’s first trial on 18 December 2020 were arrested for infringing health quarantine. Hence, the crackdown seems effective in deterring many Islamist sympathisers from going to the streets.

At the same time, the anti-radicalism campaign’s reliance on excessive force is concerning . The police are increasingly willing to use violent methods in response to demonstrations. We have seen this inclination since 2019, during the post-election riots in which hundreds of police officers were injured and a police dormitory building was burned (while several civilians were killed). Since then, the police have used force more frequently as a pre-emptive strategy to handle anti-government demonstrations. And, particularly in recent mobilisations that accompanied Rizieq’s trials, the police have consistently deployed large forces and brazenly shot teargas at protestors who were unarmed and in relatively small numbers.

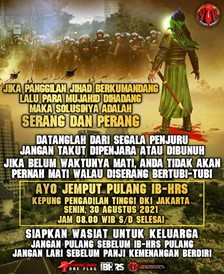

The excessive use of force in turn makes Islamist opposition more combative, claiming self-defence. Online propaganda by FPI supporters increasingly displays violent imagery. For example, one poster reads: “when the call for jihad comes and the mujahidin are being blocked, the solution is attack and war! Come from all directions, don’t be afraid of getting imprisoned or killed. Let’s storm the Jakarta High Court and free our Grand Imam! Write a will for your family [i.e. prepare to die]”. Such posters are certainly a far cry from the imagery of ‘super peaceful rallies’ that Islamists propagated—and indeed observed—in 2016 and 2017.

Islamists and Anti-Vaccine Narratives

The repression also has public health costs as some Islamist groups agitate against the government’s COVID vaccination program. It is important to note that Islamist groups are not unanimous on the vaccine issue. On the one hand, many conservative clerics, including Salafis and HTI recommended vaccination. Felix Siauw, a celebrity preacher affiliated with HTI, says that Islam does not prohibit vaccination and in fact, he claims, the Ottoman Caliphate invented and applied smallpox immunisation long before the Europeans. On the other hand, FPI-affiliated media and 212 alumni groups have spearheaded anti-vax campaigns.

FPI’s attitude is particularly interesting. At the beginning of the pandemic, FPI was relatively supportive of the public health campaign especially the Jakarta governor’s initiative. In April 2020, Rizieq called on his supporters to stop speculating about the origins of COVID-19 because the virus is real and that everyone must set aside their political differences to fight it together. FPI also ridiculed as irrational the government’s initial denial of COVID and supported Anies Baswedan’s lockdown policy in Jakarta. But now that the central government has become more serious in implementing social restriction and vaccination, FPI has shifted positions.

It is worth noting that Rizieq has not issued an official statement regarding the vaccine. However, FPI-affiliated media and various 212 alumni groups have recently contributed to spreading anti-vaccine propaganda. They are quite inclusive in their conspiracy repertoires, borrowing and modifying western right-wing narratives. For instance they told online followers that Bill Gates is using vaccines to mass-implant microchips and take control of the human race, especially resource-rich Muslim countries, and that Jokowi is helping him to create a New World Order.

What explains Islamist reversion to dissent? If we look at pro-FPI Telegram channels, most narratives on COVID vaccine are not about whether it is halal or haram. This is in part because the government has, from the outset, engaged the Indonesian Ulama Council (MUI) and major Islamic organisations to verify the halal status of the state’s preferred vaccines, Sinovac and Astrazeneca. MUI’s seal of approval makes it hard for Islamists to attack the vaccine on religious ground. So, in addition to the political conspiracy behind the vaccine, Islamist anti-vaxers focused on its supposedly dangerous side effects, such as disgusting skin diseases, heart inflammation and death. The vaccine rejection is not as closely connected to anti-China sentiment as assumed by some observers. Many of the pro-Rizieq Islamists and 212 Alumni groups do not just reject Sinovac and Sinofarm, but also all other brands including Pfizer and Moderna.

If religion and anti-China sentiment are not the primary reasons, why did some Islamists suddenly go from being health conscious to vaccine sceptical? There is no particularly coherent reason other than pure spite and animosity towards Jokowi. Some Islamist supporters with whom I spoke confirmed that they were aware of MUI’s religious endorsement of the vaccine and of similar fatwa issued by Middle Eastern ulama. However, they chose not to be vaccinated because Jokowi is “forcing” people by making vaccine mandatory. Some also said that they do not trust the government’s reassurances about vaccine side effects. The fact that the government exploited public health regulations to punish Islamist activists does little to gain trust. That said, my interviewees were quick to add that they still contribute to pandemic eradication in “their own ways” such as praying, wearing masks and taking herbal supplements. This anecdotal evidence suggests that at least one segment of the Islamist community opposes public health regulations due to deepening disillusionment with the government.

In defence of pluralism?

Illiberal suppression has been framed in terms of defending pluralism and religious freedom. However, there are compelling reasons to believe that it has not been worthwhile for the protection of minorities. Wahid Foundation’s 2020 data comparing violations of religious freedom during President Yudhono and Jokowi presidencies shows that the overall trends have barely changed (from 1,110 incidents under Yudhoyono to 1,101 cases in Jokowi era). Surprisingly, state-perpetrated violations have increased under Jokowi (from 419 to 524 cases). The Setara Institute recorded 422 violations of religious freedom in 2020 alone, 56 percent of which were conducted by state actors. In addition, rights advocacy groups have reported growing persecution of LGBT citizens, including through police raids on so-called gay massage parlors and private parties.

The attack on an Ahmadiyah mosque in Sintang, West Kalimantan on 3 September is but one indication that the existing anti-radicalism campaign has merely served as a political weapon to target government enemies, rather than defending minorities. The crackdown simply masks the complex problems underlying religious and sexual discriminations in Indonesia, in particular the frequent involvement of state actors and the impunity afforded to them. In November 2020, the East Java government reportedly facilitated the conversion of a long-persecuted Shi’a minority as a prerequisite for returning to their predominantly-Sunni hometown of Sampang. Even after the conversion, the internally displaced Shi’a families have not been able to go home due to objections from the Sampang ulama and community elders. Last June, the mayor of Bogor, West Java unilaterally relocated the GKI Yasmin Church following a 15 year-long sectarian agitation to deny it building permit. The mayor stated that his government gifted the land to the church as compensation, and that it was a win-win solution to create religious harmony without upsetting the majority.

The above examples remind us that the perpetrators of anti-minority violence are not limited to organised groups like FPI. It often involves state apparatuses, community leaders and ordinary citizens. For instance in the latest case of anti-Ahmadi violence in West Kalimantan, the district head with the support of the local police chief and military commander closed off the mosque, citing the 2008 Joint Ministerial Decree on Ahmadiyah which effectively restricts the rights of Ahmadis to practice their beliefs. Such official endorsement in turn emboldened a local mob—backed by community leaders—who had been agitating against the Ahmadis. Video footage online shows attending police officers standing in silence as the attackers burned the mosque to the ground.

The banning of FPI or any other “anti-Pancasila” group is not a shortcut to ending deep-seated discrimination against minorities. For this, the government will need to address problematic regulations which formalise discrimination against certain minorities and end the impunity afforded to perpetrators under the guise of respecting the majority will or preserving religious harmony.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss