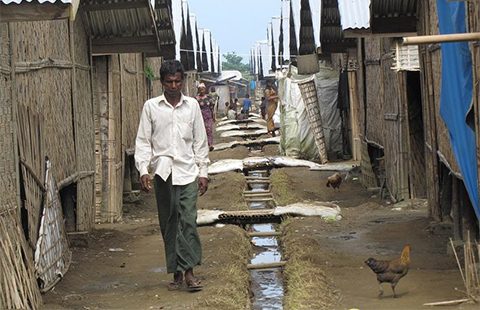

A Rohingya man walks through a camp for the internally displaced in Myanmar. Photo byMathias Eick/ European Commission.

Long the pervue of the ‘West’, new players are changing the face of humanitarian assistance across the region and the globe.

There was some good news for some of the world’s most desperate over the weekend, with the Global Humanitarian Assistance Report showing that donations rose to a record high last year.

Donors gave US $24.5 billion in 2014, with all of 2013’s largest donors giving more. However, with the good news there was some bad, the report also noting that despite the increase, it still wasn’t enough.

And it gets more depressing, with 2014 also setting a new record for refugees. According to the UN Refugee Agency’s annual report, there are now 59.5 million forcibly displaced people across the globe. Of these, 13.9 million were forced to flee their homes in 2014. No wonder they are calling it a record year in human misery.

In the wake of the findings, UN High Commissioner for Refugees, Ant├│nio Guterres came out swinging, saying:

We need an unprecedented humanitarian response and a renewed global commitment to tolerance and protection for people fleeing conflict and persecution.

But there still is hope; and it comes in the form of new players, particularly from the global South, who are starting to meaningfully contribute to the international humanitarian system.

For many decades humanitarianism and the international humanitarian system has been regarded as the province of the global North. Western states and organisations have been the principal actors and dominated its core institutions.

This, however, is changing with actors from the global South becoming increasingly important and visible. Though the United States and the European Union remain the largest donors, humanitarian assistance from states not listed in the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee rose from some $34 million in 2000 to $1.9 billion in 2015.

And some countries are going from being solely aid recipients to also being donors. According to the UNOCHA Financial Tracking Service, Indonesia provided US $2,284,875 in humanitarian assistance in 2014. This is up from 2013, though not massively. But there has been significant and steady increases over the last decade or so. The majority of recent funding went to the Philippines in the wake of Typhoon Haiyan.

Indonesia’s peak was 2010 when it donated US $6,900,000. The breakdown of this aid is interesting, with almost half going to Pakistan after the devastating earthquake there. But substantial donations also went to Haiti, Chile and even Australia, which received $1,000,0000 after floods in the state of Queensland.

Today, ASEAN also has its Coordinating Centre for Humanitarian Assistance on disaster management, which sees the 10 member states work with international donors and the UN on disaster relief and other humanitarian crises. We are also witnessing the growing prominence of Southern NGOs, such as Mercy Malaysia and the Indonesia-based Muhammadiyah.

But what are the implications of this growing diversity for the international humanitarian system? And how would it work in a complex region like Southeast Asia, which is defined by complex and divisive humanitarian issues like the Rohingya crisis?

In the case of the Rohingya, here are a people who have been denied citizenship; suffered ethnic- and sectarian-fuelled violence, imploding in deadly riots in 2012; and who are locked away in temporary camps which some have described as open-air prisons. While 140,000 are in these camps for the displaced, more than 700,000 Rohingya have been left stateless.

Such persecution has seen thousands flee, taking to the sea to seek shelter and safety elsewhere; not always forthcoming as evidenced by May’s Asian boat crisis and the push backs from Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand and Australia.

On top of this, the Myanmar government systematically restricts humanitarian aid to the Rohingya, and in the wake of violence in 2014 more than 1,000 aid workers in Rakhine State were forced to relocate, meaning even less access to essential services.

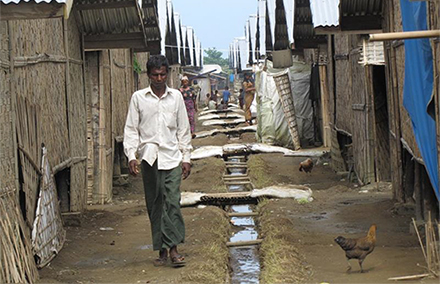

A woman and child receive medical assistance in Rakhine State. Photo by Mathias Eick/ European Commission.

Could new players and a changing system help solve this crisis? Possibly and possibly not. It comes down to what humanitarian assistance may look and how it would operate in a rapidly-shifting context.

The changing dynamic in the international system could be viewed as demonstrating a healthy pluralism in humanitarianism, but there are concerns of diversity fuelling the fragmentation of the system. In particular, traditional doors are concerned with the weak integration of new actors into the institutions and structures of the system.

Traditional donors are further concerned that new actors from the global South operate different models of assistance that could undermine the principles and practices of the system, which are typically viewed as based on the principles of impartiality, neutrality and independence. For instance the predominance of the state in China’s humanitarian system and its preference for government to government assistance are viewed as potentially undermining the independence of humanitarian assistance from broader political objectives.

The prominence of faith-based organisations in the humanitarian sector elsewhere in the global South has been viewed as potentially undermining principles of impartiality, as is the tendency of actors from the global South to be more likely to provide assistance in cases of natural disasters rather than complex emergencies.

For their part, actors from the global South have been concerned with the domination of the humanitarian system by Western actors and the degree to which they have set the standards of what constitutes legitimate humanitarian action. This has led to the accusation that the international humanitarian system is not “truly universal” but a Western hegemonic discourse, reflecting broader structures of inequality between the global North and the global South.

In contrast, the discourse of humanitarianism within the global South can be characterised as less an expression of the obligation of the strong to the weak than as an expression of solidarity born of mutual vulnerabilities to, for instance, natural disaster. Humanitarianism is often framed in the language of mutual assistance and reciprocity aimed at sharing knowledge and building resilience. India, for instance, does not use the language of donors and beneficiaries in its approach to aid, but of partnership.

From this perspective, the privileging of bi-lateral and government to government assistance is commensurate with a desire to ensure that humanitarianism does not become a vehicle for political interference in the affairs of other states. This is something which would sit well with ASEAN member states who are committed to non-interference in each other’s domestic politics.

Humanitarian action may also be viewed as a legitimate obligation of the state or faith-based organisations. This alternative discourse of humanitarianism suggests that approaches to humanitarianism found in the global South have been profoundly influenced by the legacy of colonialism and external control, as well as influenced by local political and social cultures.

While the belief that there is an obligation to relieve the undue suffering of others is widely shared, conceptions of what constitutes legitimate humanitarianism can vary widely and may be significantly influenced by cultural perspectives and the legacy of historical experience. There is a danger that tensions between actors, stemming from perceived cultural dissonance in humanitarianism, might bring about a “clash of cultures” that could weaken trust and cooperation across the sector, and thus contribute to fragmentation of the humanitarian system.

This heightens the need for enhanced dialogue between diverse actors. Dialogue, however, needs to be structured on a framework that facilitates a comprehensive and mutual understanding of diverse conceptions of humanitarianism; on understanding actors on their own terms rather than necessarily privileging established definitions.

Such a dialogue may not necessarily be comfortable , nor will it necessarily lead to consensus, but it is essential to identifying synergies and to finding ways to negotiate and manage differences with the goal of achieving the fundamental objective of humanitarianism: providing assistance to those in need in the most effective ways possible.

Dr Jacinta O’Hagan is a fellow at the Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs, The Australian National University. Her research interests include humanitarianism and international relations.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss