Emerging as the first act of defiance after the military coup on 1 February 2021, the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) is a general strike mobilisation spearheaded by hundreds of thousands of civil servants. The CDM has become the centre of focus for all parties involved in the post-coup era in Myanmar. To those opposing the coup and the military, the CDM is not only an anti-coup campaign but also a foundation from which to replace the military-controlled administrations. For the military and its supporters, the CDM was a surprise, and represents a threat to maintaining coercive and central power in the post-coup era—a threat that needs to be dealt with through the strongest measures available.

The civil disobedience campaign in Myanmar comprises a wide range of forms including banging pots and pans, street protests, refusal to pay bills, and boycotting state-sponsored lottery and military-affiliated businesses. However, this report, which can be downloaded by clicking on the cover image below, mainly focuses on the actions and roles of CDM civil servants, locally known as the CDMers, as the civil disobedience campaign is widely referred to the act of civil servants pledging not to work under the military. The report explains the CDM in three different phases—emergence, growth, and consolidation—by highlighting the significant developments, campaigns, and relationships among key political actors and organisations involved; it also explains the measures taken against the CDM by the military to consolidate its grip.

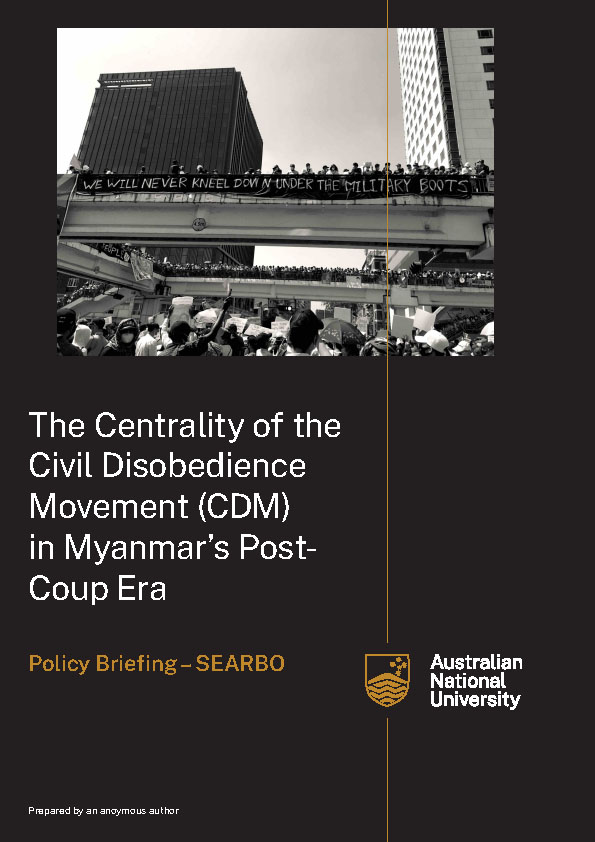

Click on the cover image below to download the full report. A Burmese translation is also included.

အစီရင်ခံစာ အပြည့်အစုံကို ရယူရန် အောက်ပါ စာမျက်နှာဖုံးပုံကို နှိပ်ပါ။ မြန်မာဘာသာပြန်လည်း ပါဝင်ပါသည်။

The coup was almost universally unpopular, sparking mass protests and boycotts against military-affiliated businesses, but also creating renewed fighting with several ethnic armed organisations, including signatories to the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA).

The Emergence of the Civil Disobedience Movement

Mobilisation of politicians and activists to launch the civil disobedience campaign was vital, but the movement began with healthcare workers refusing to go to work on the day after the coup. In his first interview with the local media on 1 February, U Win Htein, a patron of the NLD, urged the public to initiate a non-violent movement to protest against the coup, referring to the civil disobedience movement of India led by Mahatma Gandhi. A group of medical doctors from Mandalay created a network and launched the online campaign by circulating a statement condemning the military coup. A day after the coup, healthcare workers from about forty hospitals, medical institutes, and COVID-19 testing centres announced their decision to join the movement and stop work indefinitely.

Growing popularity of the Civil Disobedience Movement

The CDM gained momentum with the onset of street protests. The “CDM” and “Don’t go to office, break away” became some of the most popular slogans of the anti-coup demonstrations across the country. While some portrayed the CDM as the best bulwark in defense against the military-rule, others went further in describing the CDM as a silver bullet that could entirely end the military’s dominance in politics.

The health and education sectors have the highest volume of CDM participation. About 90% of the total number of healthcare workers reportedly joined the CDM in the first month after the coup. In some states and regions, 50 to 65 percent of teaching staff joined the movement. The participation of civil servants from three military-controlled ministries—Ministry of Defence, Ministry of Home Affairs, and Ministry of Border Affairs—has attracted much public attention. In some townships in Yangon and Mandalay, CDM participation among ward offices is as high as 100%. Moreover, at least 2,000 soldiers and police have reportedly joined the movement as of mid-August. However, all of them are low-ranking, with the highest rank being an acting police colonel and army major, proving the military’s leadership is less likely to split. The movement was nominated for the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize by six academics in Norway. It is estimated that more than 410,000 of about one million civil servants have participated in the CDM since the coup.

Consolidating the Civil Disobedience Movement

Having witnessed the deadly crackdown and impact of the CDM, the CDMers and tech-savvy youth have resorted to various tactics, including controversial online “Social Punishment” campaigns, to grow and sustain the movement. For the National Unity Government (NUG), an alternative government to the State Administration Council formed by the military, the CDM is perceived as the most important pillar in boosting domestic support; some CDM participants have become leaders of the NUG. The CRPH and civil society organisations have set up networks across the globe to finance CDM participants, despite the military’s strict control over banking systems.

With the assistance of the CDMers, there have been efforts to develop alternative administrative mechanisms to challenge the military’s rule, which are most evident in education and heath sectors. Defectors from the security forces have also been known to conduct training for the People’s Defence Forces (PDFs), liaising with others keen to defect, and leaking information about military affairs to the press and the NUG. In Kayah (Karenni) State, groups opposing the coup formed a state police force comprised of 300 CDM police as part of an alternative governing force.

Military’s Responses

Surprised by the impact and popularity of the CDM, the military has used all the tools at its disposal to weaken and co-opt the movement. The military at first only asserted authority through intimidation and warnings via their subordinates and lure the civil servants with promotions and benefits. When the movement grew exponentially, soldiers and police carried out lethal and extra-lethal violence to crackdown on the movement. As of May, more than 140,000 teaching staff were suspended. At least 252 attacks were carried out against healthcare workers and medical facilities, resulting in 25 deaths by 31 July. Hundreds of CDMers and supporters have been charged and more than 70 of their family members have been taken hostage by the military. In mid-August, more than 150 people, including 48 doctors, were still in custody in connection with the CDM and many of them were reportedly sexually abused, beaten, or tortured to death.

What kind of solidarity for what kind of Myanmar?

What do nascent solidarities mean for the future of ethno-religious minorities in a post-coup Myanmar?

Four Cs – Coup, CDM, Covid, Crisis

The continuing military oppression and the resurgence of the COVID-19 pandemic has had an impact on the momentum of the CDM movement. In the face of imminent threats and financial hardships, some participants decided to return to their previous work. Taking advantage of the outbreak, the military has been accused of attempting to revive its local administration by shutting down medical facilities run by CDMers, controlling oxygen supply plants, and forcing the public to seek the approval of the military-appointed local authorities to fill their oxygen tanks. Both the structural damage caused by the CDM and the military’s actions against the CDMers backfired as the country plunged into devastating COVID-19 third wave, leading toward the country’s worst humanitarian crisis in modern times.

There is little or no room for dialogue, or neutrality, in post-coup Myanmar, as both sides consider winning the only option. The military, which sees the CDM as a major obstacle to maintaining its political power, will continue to take the strongest possible measures against the movement. The recent assassination attempt against U Kyaw Moe Tun, the Permanent Representative of Myanmar to the United Nations, is a clear indication of how far the military will go to control its grip. On the other hand, despite a reduction in pace over the seven months since the coup, recent events have shown that the CDM still possesses popular support at home and afar. The public perception of CDMers as champions sacrificing their livelihoods for the many has changed little. Tens of thousands of CDMers will remain steadfast in their decision as long as the military is in power.

The damage caused by the coup and the pandemic are unprecedented. The health and education sectors in particular are most severely affected. With the escalation of the civil war following the NUG’s call for defensive war against the military, the humanitarian and socio-economic situations are likely to worsen. There is an urgent need for the international community to mitigate this multitude of crises. Responding to escalating hunger and medical assistance should be prioritised, but the issues of mental health and educational support should not be overlooked for much longer. However, any attempt to carry out humanitarian work without the recognition of the CDM or prioritising localisation will provoke public distrust and rejection, as admiration of the CDM is deeply ingrained in the post-coup Myanmar society.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss