When we think of a work of art, we usually imagine something on display inside a light, bright gallery – a canvas stretched behind glass, or a sculpture on a plinth. Within the white-cube of modern galleries such as Indonesia’s new Museum MACAN, such works of art are reified and untouchable.

We don’t imagine a work of art flying up and down a busy road in Padang or Bukittinggi, belching fumes and stopping for loyal passengers. These angkot (or angkutan kota, meaning city public transport) are part of every-day life for the Minangkabau people of West Sumatra. But for the rest of us, these cheap and vibrantly-adorned mini-buses offer a glimpse into the thriving pop culture that exists in a region more often known for its hot and spicy food.

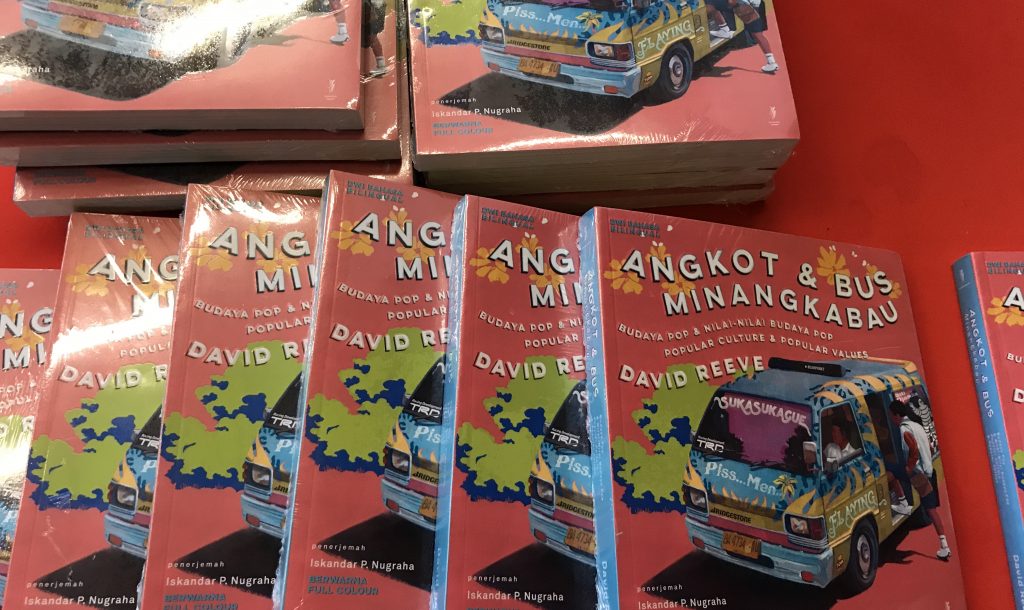

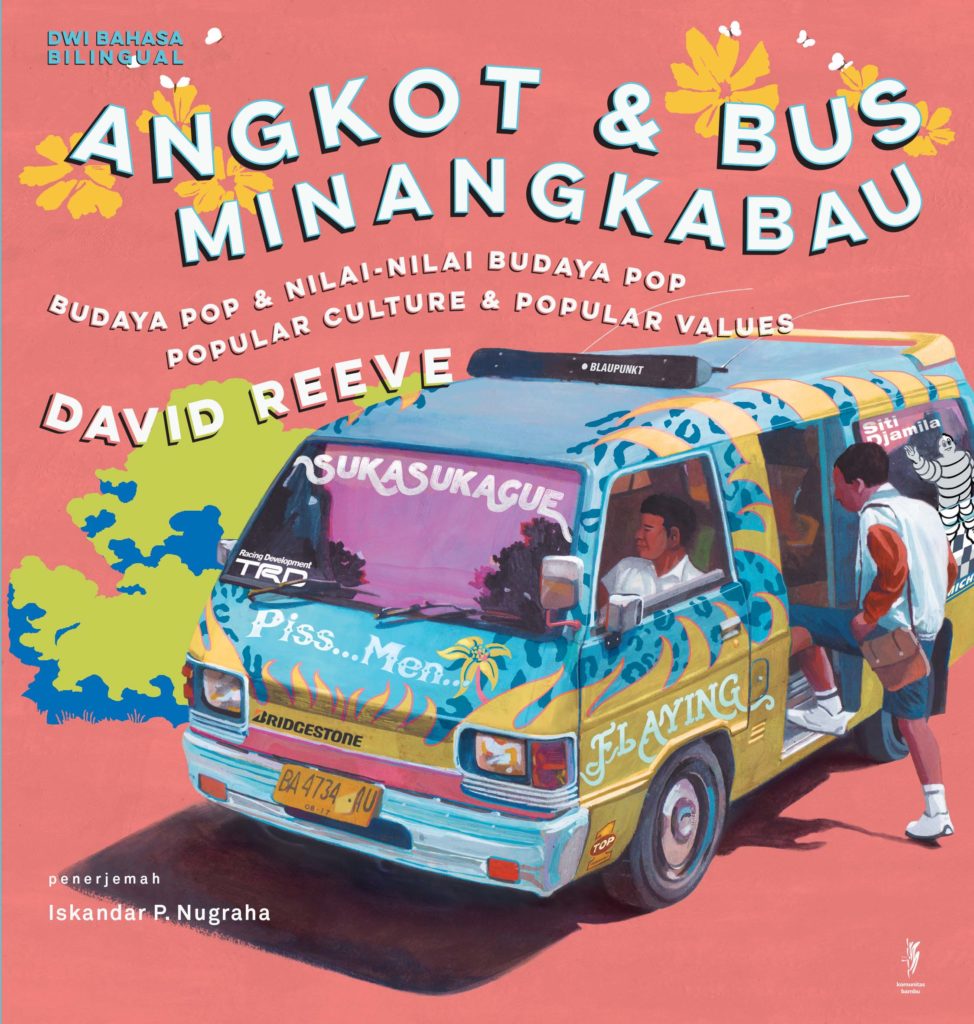

David Reeve’s new book, ‘Angkot dan Bus Minangkabau: Budaya Pop & Nilai-Nilai Budaya Pop’ (Minangkabau Angkots and Buses: Pop Culture and Pop Culture Values)

David Reeve’s new book, Angkot dan Bus Minangkabau: Budaya Pop & Nilai-Nilai Budaya Pop (Minangkabau Angkots and Buses: Pop Culture and Pop Culture Values) brings these noisy, living works of art to those of us not fortunate enough to have visited West Sumatra. What started as note-taking and (when the angkot were driving slowly enough) the occasional snapshot has turned into a full-blown publication, complete with colour photos and a collection of over 90 slogans taken from the angkot.

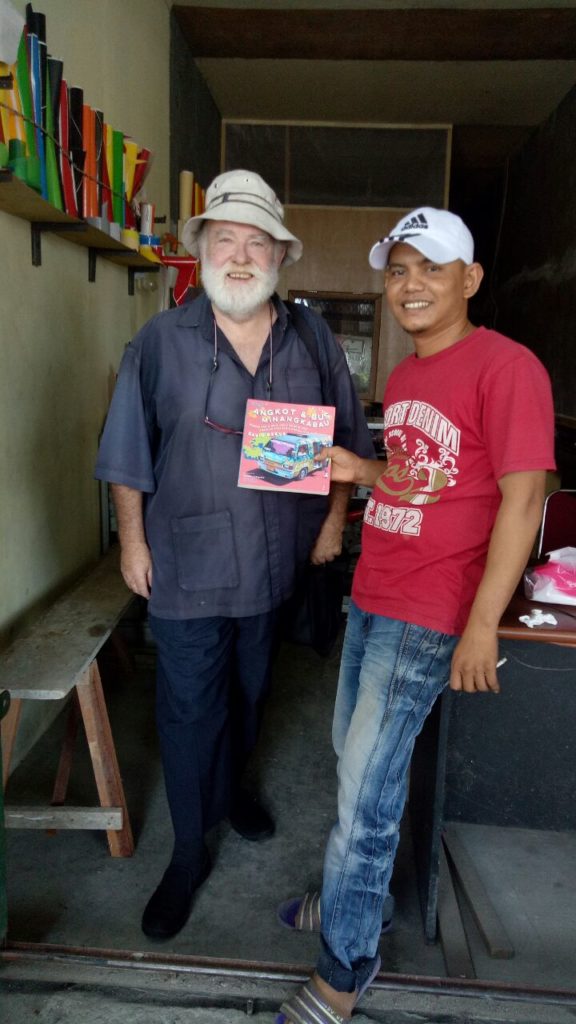

David Reeve at work on the streets of Padang, West Sumatra. Image: Detik

This bilingual publication (written concurrently in Indonesian and English, with Indonesian translations by linguist and lecturer Iskandar P. Nugraha) is the first of its kind to discuss the angkot as a cultural phenomenon and to reveal its complexity and colour. This bilingualism is one of my favourite aspects of the book, and (according to a reliable source) makes it somewhat of a popular commodity among the angkot drivers themselves.

David Reeve and a happy angkot driver. Image: David Reeve

The angkot express the ambivalent attitudes that Minangkabau have towards notions of tradition and modernity. On the one hand, the art and language use depicted on angkot derive from long-standing traditions in West Sumatra, such as the classical Malay poetic form of the pantun. On the other hand, the values that the drivers choose to express on these vehicles are palpably un-traditional. The angkot artists are preoccupied with the trappings of modernity, such as advanced technology and movie-star masculinity.

What becomes evident, says Reeve, is the yawning gap between the popular cultures expressed on the angkot, and the ‘official’ version of Minangkabau values. Whereas the angkot express ‘a yearning for speed, hi-tech, modernity, English language, masculinity and power’, the official picture of Minangkabau culture looks instead to the past – to ornate costumes and traditional textiles, architecture, song and dance, male mobility (merantau), and the way in which traditional matrilineal customs (adat) interact with deeply-held Islamic beliefs. Many of these stereotypes are grounded in the findings of intensive anthropological study of traditional Minangkabau culture over the years. By rejecting the official vision of traditional values, these angkot suggest a longing among the Minangkabau themselves for a different type of future to that which is offered by the official version.

However, Reeve does not allow us to be misled by simple dichotomies such as traditional vs. modern, or official vs. popular. Instead, he shows how the seemingly non-traditional angkot decoration has its roots in two Minangkabau customs of old – the richly-decorated bendi (traditional horse carts), and the use of linguistic games in West Sumatran society.

A bendi in Bukittinggi. Image: The Wide Angle

The Minangkabau are famous for their linguistic ability, including the performance of pantun – a type of rhyming poetry slam, competitively exchanged between family members – at special occasions such as weddings. They are also renowned for their proficiency with proverbs. It is this facility with language that makes the angkot in Minangkabau so outstanding – they are covered in slogans, phrases and words, in Indonesian, English and sometimes Arabic, as well as pictures and symbols.

Although the angkot slogans may belong to a centuries-old Minangkabau tradition of linguistic performance, they are expressed in the rapidly-transforming idiom of youth culture. The most highly-decorated angkot cater for the student and youth crowd. For a language teacher such as Reeve, who has long been interested in bahasa gaul (slang) and other dramatic and memorable language, these angkot were irresistible. The words and themes on each angkot are by turn playful, irreverent, raunchy and defiant, and combine to create what Reeve calls ‘a gaul effect’.

Front-seat fieldwork. Image: David Reeve

One of the main themes relates to motor racing, underscored by a hyper-masculine, outward-looking focus and a lust for speed and high technology. Also prevalent are catch phrases about driver attitudes, complaints about their difficult lives, and an often-juvenile attitude towards romance and sex. These are frequently juxtaposed with sentimental expressions of family values.

Many of these themes come together in the hip-hop/rap angkot song Sopir Oto (Angkot drivers) by Minangkabau rapper Tomy Bollin:

On the street, these themes and ideas are repeated endlessly as the angkot circle around the city. The full effect, however, is only possible if you look at all four sides of the angkot. As Reeve explains,

The customers can see the front approaching them, the side as the angkot stops or passes, the back as it goes away, and the outer side of other angkot as their own angkot overtakes; this is the big canvas.

But the angkot is under threat. As Reeve told The Jakarta Post, “There’s been a 10 per cent reduction in the past three years. Authorities don’t like them. The business is being killed by bigger buses and cheap credit for motorbikes.” The Go-jek effect is also a factor.

While they may not be hanging in a gallery, these angkot – anti-conservative while being grounded in tradition – are works of art nonetheless. They express not only the creativity of their decorators, but a profound gulf between different Minangkabau conceptions of tradition and modernity. That, as Reeve says, is the big canvas.

Historian and language teacher David Reeve in Indonesia. Image: David Reeve

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss