The Indonesian Marxist and anti-colonial revolutionary Tan Malaka (1894-1949) exists in two forms, real and fictional.

The real Tan Malaka was born around 1894 and had two spells at the forefront of Indonesian politics, first in the early 1920s, when he was a leader of the Communist Union of the Indies, and second during the Indonesian Revolution (1945-49), when he campaigned for a radical policy of social revolution and armed resistance against the Dutch. Between these two spells he spent twenty years in exile (1922-42), living for the most part under a variety of false identities in Siam, the Philippines, Singapore, and China.

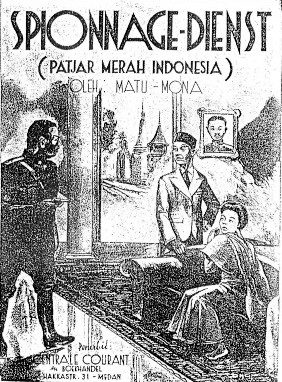

The fictional Tan Malaka was created in the 1930s by the novelist and journalist Hasbullah Parinduri (who used the pen name Matu Mona). Drawing on newspaper reports and on Tan Malaka’s letters, Matu Mona wrote a series of roman picisan (‘dime novels’) about a thinly veiled version of Tan Malaka, titled Patjar Merah Indonesia (‘The Scarlet Pimpernel of Indonesia’). These stories were inspired by Baroness Orczy’s The Scarlet Pimpernel (1905), which had been translated into Malay in 1928 and turned into a successful film in 1934.

In these stories Matu Mona reimagined Tan Malaka as an Indonesian Scarlet Pimpernel, who fought imperialism and evaded colonial authorities across Asia. The success of the stories was such that Tan Malaka and the Patjar Merah began to merge in the imagination of the Indonesian public. But what exactly was the relationship between the real Tan Malaka and his fictional alter ego?

The man and the myth

The Patjar Merah is an exaggerated version of Tan Malaka, refracted through the lens of dime novel fiction, with its tropes of adventure, mystery and romance. While Tan Malaka could speak Malay, Dutch, German, English and Mandarin, the Patjar Merah is fluent in all these languages plus French, aristocratic Thai and Arabic, with a reading knowledge of Latin, Sanskrit and Sumerian.

While Tan Malaka was something of a chameleon during his years of exile, living under Chinese and Filipino identities, the Patjar Merah is a master of disguise, known as ‘mystery man’, who assumes Thai, Russian, Arabic, Chinese, Filipino and Hawaiian identities and disguises himself as a Buddhist monk, a Philippine professor and an old woman at various points in the novels.

Tan Malaka’s personal life is also mirrored in his fictional alter ego. Tan Malaka was unusual among his peers in that he never married, in part because he had to keep moving to evade colonial police. The Patjar Merah, in the same way, puts the needs of his nation above those of his heart. In Spionnage-Dienst (‘Espionage-Service’, 1938) he repeatedly rebuffs Mademoiselle Ninon Phao, a beautiful French-Thai gadis modern (‘modern girl’), telling her ‘I am like an egg on the tip of a horn, as the saying goes … one wrong move and it will fall and shatter, this Ninon is my fate. A life like this is no good for you, a beautiful woman, a gem of your nation, ma petite sorite! Forget me, Ninon so that I may continue my journey’.

The most interesting feature of the Patjar Merah novels, however, are the differences between reality and fiction. Unlike Tan Malaka, the Patjar Merah has supernatural powers such as invulnerability, invisibility and clairvoyance, which he has acquired through his mastery of ilmu gaib (‘secret science’), an esoteric body of knowledge usually associated with Indonesian mysticism.

In the scene in which he is first introduced, the Patjar Merah reveals the nature of his powers of foresight. He tells Ninon Phao ‘I have the secret power [kekuatan gaib], just as a prophet receives a revelation, so I too see in my dreams that which will befall my loyal friends. Often I have been given a sign this way, and, as a result, although people seek me across the Far East, none have yet been able to catch me.’

The irony is that the real Tan Malaka had little time for ‘mystical’ learning, considering it pure superstition. Indeed, he was at pains to emphasise that his own method of political forecasting, derived from Marxist historical materialism, was entirely different from traditional Indonesian prophetic visions. In his 1926 book Semangat Moeda (‘The Young Spirit’) he wrote:

We communists do not get this image of communism from the passions of dreamers or astrologers… Instead we have a clear explanation from Marx, that the progress of feudalism gave rise to capitalism, and the present progress of capitalism is bringing about communism. Just as the nobles were overthrown by the capitalists, so the capitalists will be defeated by the workers. This defeat does not arise from mystical or magical [gaib] causes but for tangible reasons, which can be seen and perceived.

Yet this side of Tan Malaka, his historical materialism, disappears entirely in his fictional incarnation. The Patjar Merah is never referred to as a Marxist or a communist, only as a proud Indonesian patriot or a ksatria (‘knight’).

The Patjar Merah is also a pious Muslim. Not only does he join the Arabs in their fight against British imperialism in Palestine, he also prays at dawn and makes the pilgrimage to Mecca. In one passage, he discards his Western clothes and adopts the dress of a fakir (a Muslim ascetic). Yet there is little evidence that the real Tan Malaka was so devout. Although he came from a very religious family and received an elementary Islamic education in his youth, he was unable to read Arabic and never travelled to Mecca. It is unclear whether he was a practising Muslim in his adult life. In his book Madilog (1943), he expressed scepticism regarding certain religious beliefs, such as the divine creation of the earth and the immortality of the soul.

Why, then, did Matu Mona present Tan Malaka as a religious and mystical figure, given Tan Malaka’s own efforts to establish himself as a pragmatist and a man of science? One likely reason is that this created a more exciting character. The possession of magical powers made the Patjar Merah into a dime novel superhero, capable of wondrous feats such as disappearing when being chased by Russian secret police, or surviving being shot, all of which add to the thrill of the story and make the Patjar Merah resemble an Indonesian folk hero.

Making the Patjar Merah a devout Muslim also allowed Matu Mona to distance Tan Malaka from Marxism, which was alarmingly atheistic to many Indonesian Muslims. As a result, the Patjar Merah, and by extension Tan Malaka himself, became a more sympathetic character for the largely Muslim Indonesian reading public. Tan Malaka’s own real-life habits, such as making pronouncements about the future and living a simple, chaste life, may also have led Matu Mona to characterise him as a latter-day Islamic holy man.

Fact meets fiction

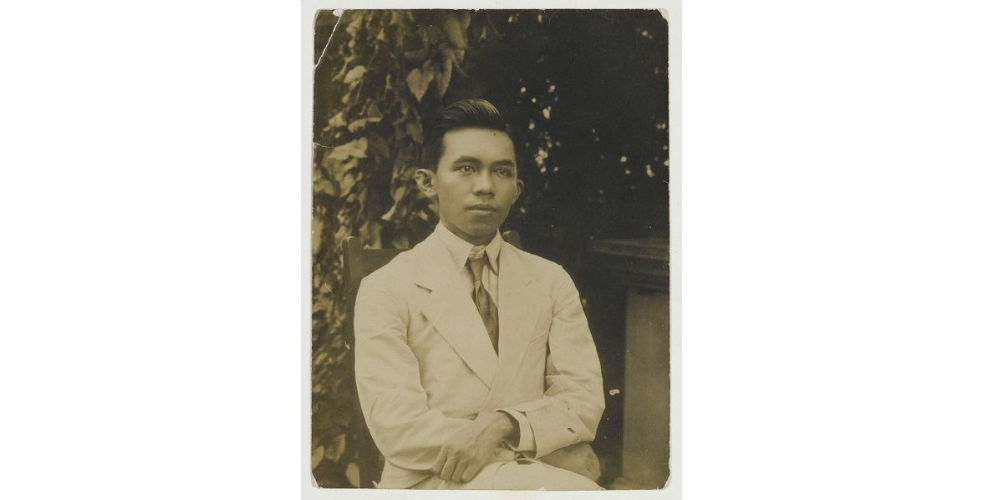

Photograph: Ibrahim Datoek Tan Malaka. Image courtesy KITLV, CC-BY License

Matu Mona’s Patjar Merah novels were very successful, so successful that other authors began to publish Patjar Merah stories of their own in the early 1940s. His novels were widely read during the Japanese occupation of Indonesia (1942-45) and were especially popular among members of the anti-Japanese underground, who likely saw a kindred spirit in the uncompromisingly anti-imperialist Patjar Merah.

By the time he returned to Indonesia, in secret, in 1942, Tan Malaka was firmly associated with the Patjar Merah. In his autobiography, he describes the following scene in a Medan book stall in 1942, shortly after his return (when he was still incognito, going by the name Hussein):

I had just begun leafing through a book when the vendor put one in my hands, saying, “This is a good book, and it’s very popular.” It was Patjar Merah (The Scarlet Pimpernel) by Matu Mona. This was the first time I had come across either the book or the author. I had only just begun to look at it when the vendor came up to me again and whispered, “You know, Tan Malaka is in Padang. He spoke today in the Padang square. He has a high position in the Japanese army.” I asked Tan Malaka’s rank, and he answered, “They say he’s a colonel.”

The popularity of the Patjar Merah stories added to Tan Malaka’s charismatic appeal when he revealed his true identity and returned to public politics at the end of 1945. Despite having been away for over twenty years, he was able to quickly build a large following around himself, organising support for his policy of armed resistance against the Dutch.

Tan Malaka himself was conscious of the benefits of playing to his larger-than-life image. In Madilog (1943) and in his memoir Dari Penjara ke Penjara (‘From Jail to Jail’, 1948), written after he was imprisoned by his political opponents in 1946, he burnished his own reputation as a veteran revolutionary and man of mystery, giving details of the secret codes and aliases he had used to evade colonial police during his years of exile. In this way he showed that he had the necessary experience to be a national leader in the fight against imperialism – a real-life Patjar Merah.

Writing history in the Indian Ocean world

Writing history in the Indian Ocean world was the result of a complex interplay of global norms and local conditions of textual production.

Yet in a sense the fictional Tan Malaka came to displace the real one. Adam Malik, who was for a time a supporter of Tan Malaka, wrote in his autobiography that during the revolution Tan Malaka was rumored to be able to vanish and to appear in two different places at the same time. According to Malik, these rumours turned Tan Malaka into ‘a superhuman being on an equal footing with the gods.’ The Indonesian historian Bonnie Triyana has written that in the 1950s the legend of Tan Malaka’s ability to teleport was widespread in the towns and villages of his home region of Minangkabau.

Towards the end of his life, Tan Malaka came to believe his own myth. Despite his commitments to Marxism and ‘scientific’ politics, at times he saw himself in almost superhuman terms. In 1980 one of his former associates, Bujung Siregar, recalled to the Dutch historian Harry Poeze that Tan Malaka had once told him ‘Jesus Christ left the Bible behind, Mohamad the Koran, and I leave only Madilog. This is no work of propaganda, but sets down a way of thinking, an approach to and analysis of all questions. Madilog is my guide; my death is no serious matter, for Madilog exists’ – words that could have come from the Patjar Merah himself.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss