The coup by the National Council for Peace and Order under General Prayuth Chan-ocha will lead to an acceleration of Thaksinomics, rather than its demise.

The junta has already embraced key elements of the Thaksin’s dual track development policy, combining international economic liberalism with domestic populist schemes, by reviving the 2-trillion baht infrastructure program and rapidly making payments to farmers under the rice-pledging program. As hypocrisy knows few boundaries, Democrat and former Finance Minister Korn Chatikavanij has quickly hailed the junta’s payments to farmers under the rice scheme, after years of criticizing the same program when implemented by Yingluck.

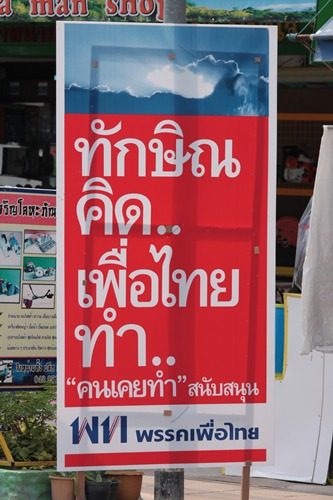

A key message in the 2012 election campaign was that “Thaksin Thinks, Puea Thai Acts” and the junta seemingly tries to adapt a “Thaksin Thinks, Prayuth Acts” model when restoring key economic policies of the party they just overthrew.

Economic policies may be a minor issue compared to the gross human rights violation in the aftermath of the coup, including arbitrary detentions, restrictions on free speech, and the suspension of democracy. Yet, reviving the ailing economy is top priority for Thailand military junta and its success in reinitiating growth will have a major impact on events in the aftermath of the coup.

Realizing that the complexities of a modern economy is beyond the grasp of aging generals, the junta quickly brought in a policy making team largely made up of former Thaksin loyalists. Somkid Jatusripitak a co-founder of Thai Rak Thai that held both commerce and finance positions in Thaksin cabinets will oversee foreign affairs for the military government. Pridiyathorn Devakula overseeing the juntas economic policy, was appointed Governor of Bank of Thailand during the first Thaksin administration. He also served as finance minister in the military government following the 2006 coup that introduced disastrous capital controls leading to a collapse of the stock market. Narongchai Akrasanee, a former Minister of Commerce that served as an advisor to the Thaksin government, will assist Pridiyathorn.

The rapid adoption of Thaksinomics by the junta, is a reflection of the model’s total dominance within Thailand’s policy circles. It’s dual track nature – with economic liberalism to attract foreign capital combined with populist domestic programs to attract broad domestic support – is attractive to policy makers seeking to both maintain Bangkok centered economic growth and appease the largely rural electorate. Thaksinomics is likely to continue to dominate the country’s economic policies given the repeated electoral success of Thaksin’s political parties and the lack of credible alternative models, as the elitist sufficiency economy has failed to attract widespread rural support.

The junta’s economic team faces a difficult task with an economy in contraction. Political uncertainty has stalled investment and consumer sentiment fell to a 12-year low in the months before the coup. Key economic decisions will put the military government at a test. While future support to rice farmers will be difficult to swallow for the Bangkok-based supporters of the military takeover, removing all subsidies is out of the question. With market prices at a third of the price guaranteed under the Yingluck government program, ending rice subsidies would ensure a quick demise of any rural support for the junta. We are most likely to see a continuation of rice support and other populist programs under new names, in moves similar to the rebranding of Thaksinite policies done after the 2006 coup and the Abhisit government.

The suspension of all checks and balances under direct military rule opens up opportunities for gross corruption. A country with a long history of military power grabs, Thai generals inevitably amass huge fortunes while in power. Resumption of the 2 billion-baht infrastructure program, appointment of generals to the boards of state-owned enterprises and the inevitable increase of the military budget will ensure that the junta leaders not only grab political power, but also a fair share of the Thailand’s riches.

Anders Engvall is a Research Fellow at the Stockholm School of Economics

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss