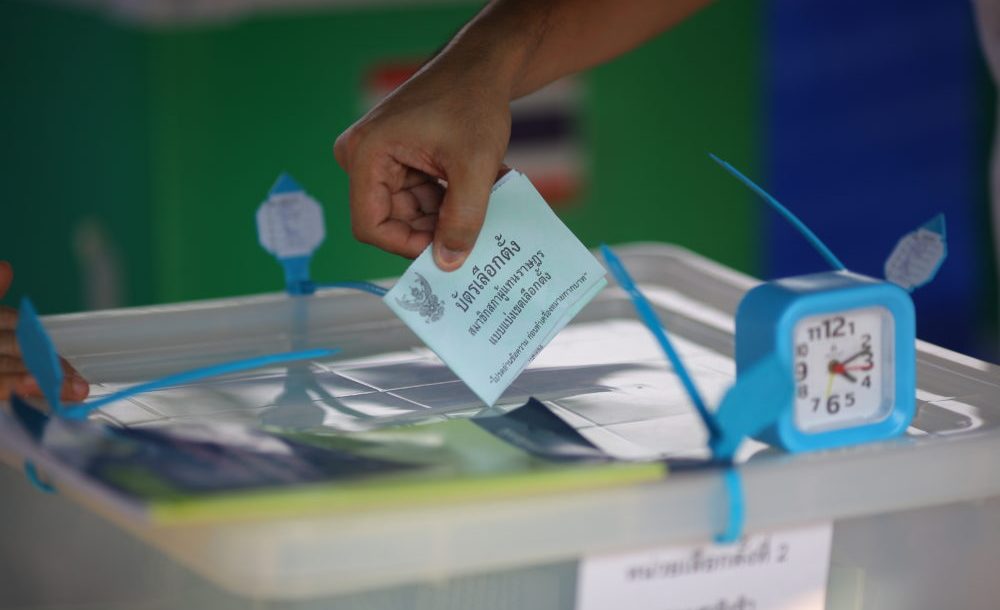

Thailand’s 2019 general election is a spectacular disaster. A large number of voters were determined to get to the ballot box in this most expensive election, which costed a total of 5.8 billion baht to administer. But the integrity of this election is irreparably damaged. More than three weeks later, there remains much confusion and unresolved allegations of fraud. Wrong ballots were given (some were delivered to the wrong destination or not collected by the authorities). Army conscripts were filmed casting votes under the monitoring of a senior officer. Counting lacked standards, with election officials arbitrarily dismissing or approving ballots. When the Election Commission released preliminary results, figures were repeatedly corrected as the public noticed irregularities.

Things are not always perfect. But the stake of this election is unusually high, because it will determine the junta’s future. Given the close margins reported in the preliminary results, every vote counts and no one wants theirs to be wasted or rigged. All of these mistakes, and many others, have convinced the public that this election is not an exit from the political quagmire but a sham to extend the junta’s stay in power.

At the heart of the controversies sits the Election Commission of Thailand. The costly and disastrous election has exposed the problematic yet often overlooked role of the Commission and other independent watchdog agencies in thwarting democratic progress.

The Election Commission was first established in the 1997 Constitution, tasked with taking over the handling of elections from the Ministry of Interior. It was designed to be a body of impartial experts, insulated from political influence, and vested with the duty to hold free and fair elections. But trust in this constitutional innovation has been nosediving.

The first Election Commission (1997–2001) was fine. But the second Election Commission (2001–06) was accused of bias in favour of Thaksin Shinawatra during the controversial 2006 election, which was ultimate invalidated by the Constitutional Court and lay the conditions for the coup d’état that year. The Commissioners would later be imprisoned for misconduct. The third Election Commission (2006–13) was appointed by the 2006 junta. It ran two elections in 2007 and 2011, from which it filed several petitions to the Constitutional Court for party dissolutions. As a result, Thaksin-affiliated parties were dissolved, resulting in a change to a Democrat-led government in 2008. The fourth Election Commission (2013–18) again caused huge controversy when it refused to organise the 2014 general election amidst anti-democracy protests. Its foot-dragging led to the Constitutional Court’s invalidation of the 2014 election and another coup.

The fifth and current Election Commission (2018–present) was installed by the junta-appointed National Legislative Assembly (NLA). Its appointment history underpinned suspicions prior to the 2019 election that the body would collude with the NCPO. Those suspicions were confirmed when the Commission refused to investigate a campaign finance scandal involving the NCPO’s proxy, the Phalang Pracharath Party, but swiftly dissolved Thai Raksa Chart, one of Thaksin’s proxies.

Despite the 1997 Constitution’s vibrant democratic spirit and its commendable electoral system, its master design depended on guardians safeguarding the political process. Some administrative functions were reassigned to new agencies no longer under the cabinet’s control. These watchdog agencies enjoy managerial independence as well as operational independence. They were to have their own budgets and personnel and enjoyed freedom from the cabinet’s intervention. They possess encompassing powers not only to enforce laws and regulations, but quasi-judicial rule-making authority. At the heart of these agencies is independence from political oversight.

Not belonging to the conventional separation-of-power trinity, the Election Commission’s independence from political oversight raised the question of accountability—which still no one has attempted to seriously answer. The Commission, for example, falls under the jurisdiction of neither the Constitutional Court nor the Administrative Court, which review legislative and administrative acts respectively. Although Commissioners are still subject to criminal liability and impeachment, it is unlikely that the Criminal Court nor the Senate, generally considered part of conservative networks, would be willing to punish watchdog agencies. Besides the second Election Commission which was accused of colluding with Thaksin, Commissioners appear immune from legal and political liability.

What’s the role of a Constitutional Court in a military dictatorship? On the dissolution of Thai Raksa Chart

In Thailand, the function of the constitution is not to limit the power of the king, but to reflect the king’s will.

Instead, conservative elites have succeeded in capturing appointments to the Election Commission. After 2006, political representatives were barred from the appointment process, which was then carried out by members of the judiciary and other watchdog agencies. Candidates were said to become less sympathetic to the democratic cause. Although the initial problem with the watchdog agencies was that some of them were allegedly influenced by Thaksin, the problem since 2006 is that these agencies have become more hostile to Thaksin, and democracy. Subsequent junta-backed constitutions have kept expanding their power and isolating them further from oversight.

The Election Commission will not finalise the election result until 9 May, after the coronation of King Vajiralongkorn. Meanwhile, it will begin hearing complaints and disqualifying MP candidates, so it is speculated that the it may be able to tilt the outcome in favour of Phalang Pracharath. Simultaneously, the public is calling for accountability and transparency. It is difficult to know if every mistake in this election was intentional. It is possible that there were rigging attempts, at least at the local level, but some discrepancies may simply have been due to incompetence and ignorance. Information about the dissolved Thai Raksa Chart was still displayed at some voting booths. When counting the votes, district volunteers confused parties with similar names. The electronic tallying system broke down so local units had to submit their counts manually, resulting in more mistakes.

All the same, there is broad consensus that the Election Commission is unfit to fulfil its assignment. Unfortunately, the public can do little to hold this structurally independent, yet ideologically biased, body accountable. Millions signed a petition to call for impeachment but the Commission has struck back by filing defamation charge against a few activists—a move further deteriorating the body’s credibility.

Lack of accountability enables the Election Commission to stonewall the public’s requests to disclose the raw seat distributions from all 350 constituencies. It also refuses to reveal how exactly it will calculate party-list MPs, having provided only a worded description (but not a mathematical formula) that can be interpreted in several ways. An arbitrary calculation of party-list MPs may affect the strength of representation of up to 25 parties. About a dozen small parties that are predicted to receive a single party-list seat under the Commission’s latest computation will probably join the Phalang Pracharath coalition. To complicate the matter, the Commission has decided to ask the Constitutional Court to endorse its calculation—a subject clearly outside the court’s jurisdiction.

The only long-term solution—should Thailand desire no more disastrous elections, as well as political deadlock and unnecessary constitutional disputes—is to reform the Election Commission. That means addressing flaws to the design of the country’s watchdog agencies, and admitting that too much independence has backfired. But reform can only happen if the democratic forces win the election, of which the Election Commission is itself a gate keeper. The battle is being fought uphill.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss