In a lengthy and detailed critique of Duncan McCargo’s memorable article on network monarchy Yoshinori Nishizaki, a Singapore-based political scientist, has mapped out marriage and kin relations among Thai royalty and nobility from the late nineteenth century through the 2000s. Map is the operative metaphor: to showcase his data Nishizaki produces 11 figures that graphically illustrate the labyrinthine relationships he has unearthed. Unaided by a fancy software program, he produced the data by hunting down the connections and painstakingly assembling them piece-by-piece manually, so to speak, as if putting together a jigsaw puzzle. To spare the reader the trouble of following the network pathways in the graphics, he renders them in prose. The writing in these sections, the heart of the article, is so mind-numbing in its density as to be almost unreadable.

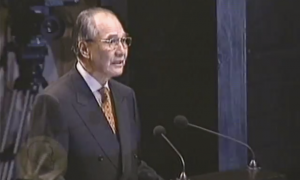

Nishizaki’s critique comes out of a larger monograph in progress. To shape the vast amount of data into a case study, Nishizaki focuses on the consanguineous and marriage relationships of Anand Panyarachun, a former prime minister (1991-1992) who has been ambassador to the United Nations (1967-72) and the USA (1972-75), and chairman of the Constitution Drafting Committee that produced the 1997 Peoples Constitution. Anand has held important roles in business and is chairman of the Siam Commercial Bank, which is part of the Crown Property Bureau, the investment arm of the royal family. Anand epitomises the “good people” that King Bhumibol spoke often about as desirable leaders in public life. Nishizaki’s aim is to disclose the Panyarachun family’s complex ties with elite families, the princely and bureaucratic families whose roots reach back to the pre-1932 period of absolute monarchy.

With the death of King Bhumipol Adulyadej in 2016 and a new monarch on the throne, McCargo and some other observers may feel that the concept of network monarchy, one of those euphoric couplets that Robert Cribb wrote so tellingly about in relation to Indonesian studies, has served its time and must be allowed to rest in peace. McCargo published his article at the height of the late king’s popularity as national celebrations neared for his sixth decade on the throne. Bhumipol’s son now reigns as the tenth king in the dynasty, a man with an eye-catching life-style who has yet to earn the public approbation that grew to the reverence enjoyed by his father.

Nishizaki, by publishing this provocative study, would beg to differ that network monarchy has passed its shelf life. He points out that McCargo was well aware that his article was only a sketch calling for further elaboration. In McCargo’s view network monarchy is a creature of Bhumipol’s activism, a personalistic strategy not only to protect the supreme institution but also to enhance its prestige and power. The core of the network was the Privy Council to which the king appointed men drawn from state institutions, many with ties to distinguished families. In fact, says Nishizaki, the vast personal patronage network credited to Bhumipol was not his creation alone but rather an extension of family ties forged decades earlier. Bhumipol simply expanded for his own purposes a political resource he had inherited. The late king did not invent network monarchy, he merely exploited it.

What can we learn from Nishizaki’s research? Buried in the network data is an explanation of one of the pivotal moments in modern Thai history, the misnamed revolution of 1932, an event described by more than one historian as mysterious, even bizarre. Why did the leaders of the 1932 coup, who had seized control of the government, allow the monarchy to stand, albeit in a reduced role? Why, for example, had they not exiled the king as had some colonial regimes who dismantled monarchical regimes elsewhere in the region? A Thai academic colleague once visited Pridi Banomyong (1900-1983) in Paris on a pilgrimage taken by more than one Thai intellectual curious to consult one of the 1932 coup leaders and learn first-hand what had happened. I cannot recall how my colleague posed these questions, but the reply Pridi gave him was enigmatic in the version that reached me: “we couldn’t do it, because we were all of the same group.” My conversation was in English, and I do recall the word was group.

Nishizaki’s answer to the questions is that the coup leaders deliberately left the revolution unfinished, because they desired continuity rather than disruption. The same group, as Pridi put it in the conversation shared with me, referred to the 1932 coup members, including Phibun Songkhram, who were tied by marriage to the monarchical elites they were rebelling against. Pridi himself also had ties to noble lineages. They did not want a rupture that would alter the nature of Siamese politics and strip their relatives of their patrimony and connections to power holders in the new order through which they might advance their own interests. The Russian Revolution had occurred not many years before, and the fate of those on the wrong side of history was well-known.

What kind of influence do the interlocking princely and bureaucratic families exert on policy and public life? Here Nishizaki is sparing in his analysis, and we will have to wait to see if he is more forthcoming in the monograph. He makes a strong case for a royalist constituency (my word, not his); he is clear that the network is not monolithic, it does not move as a bloc. Not every person who turns up in the 11 network maps agrees with everyone else, not everyone will toe the royalist line at every juncture. There would be different kinds of royalists and royalisms in the bevy of names on the network maps, and Nishizaki is aware of the occasional ideological dissonance that results. He does extend his analysis up to recent times by illustrating how family relations with royalist elites explain appointments to the current pro-junta Senate, and to the Constitution Drafting Assembly and the National Reform council established after the coups in 2006 and 2014.

Thailand’s rule of declining descent ensures that descendants of kings and the so-called second kings lose their royal designations after four generations, the last being Mom Luang. The princely and bureaucratic families had their family names conferred mostly by the sixth Bangkok king, Vajiravudh (r. 1910-1925), and these monikers have stuck as badges of royal affiliation. The families have continued to intermarry in the decades since 1932 to produce a kind of diluted hereditary hierarchy that still wields influence and power. They have a stake in preserving the monarchy because their social status and prestige depends on it, and the monarchy has relied on them for its own power and prestige. Nishizaki’s analysis leaves us to wonder how long or whether this symbiosis, the modus operandi of network monarchy, will last.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss