There have been some important changes in the electoral rules, resulting from two sets of constitutional amendments, Articles 93-98, these past months. The implications of these changes could be decisive in determining who gets to form the government in July.

Members of Parliament

The lower house shall comprise 500 elected representatives: 375 MPs will come from single-member constituencies, whereas 125 MPs will come from a closed-list proportional system. The constitutional amendments of 2011 have increased the number of MPs to 500 (from 480 in the 2007 election) and reduced the number of MPs from the constituency system from 400 to 375. By contrast, the number of party-list MPs increases from 80 to 125.

Constituency System

There are 375 constituencies in Thailand, each representing roughly 170,000 people. Each constituency elects one MP to parliament. Since it is a winner-takes-all system, political parties field their most seasoned politicians (or their relatives), who are often well respected and highly influential in their districts.

From Multi-Member Constituency to Single-Member Constituency

The idea of “one vote, one district” means if a party comes in second or third, their votes don’t matter. Only the absolute winner gets the seat.

Party-list System

Each party fields up to 125 candidates for the same number of seats. Voters get to choose only one party for the party-list system which means he/she selects all candidates on the list. Since it is a closed-list PR voting system, each party ranks candidates based on their reputation and experience. The list is considered a “safe zone” for some candidates because if they’re ranked high enough on the list they are guaranteed to be elected without having to directly compete with candidates from other parties Pheua Thai, for example, is fielding all the key Red Shirt candidates, such as Jatuporn Prompan and Nattawut Sai-keau, on the party list because the party wants to make sure they become MPs without too much risk.

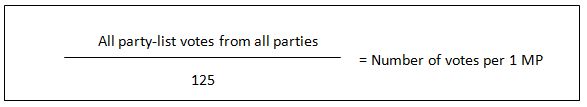

The way to calculate the number of candidates from each party elected in the party-list system is as follows:

- Add up the total number of party-list votes for all parties;

- Divide the total number of votes 125 and you will get the figure for the number of votes required per party-list MP;

- Divide the votes for each party by the average number of votes per party-list MP to determine how many party-list MPs the party gets;

- If we don’t get 125 MPs then whichever party has the highest leftover points gets one more MP.

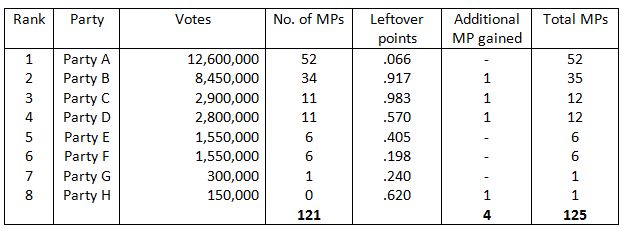

For example, 8 parties field candidates in the party-list system and each party gets the following number of votes:

- Add up all the votes gained by all parties = 30,250,000

- Divide with 125 = 242,000

- Divide the total number of votes for each party by 242,000.

- For Party A, 12,600,000 ├╖ 242,000 = 52.661. This means Party A gets 52 seats with 66,100 leftover points.

No Threshold on List PR System

The amendments have dropped the 5% threshold for seats in the party-list system. In the 2007 election, parties were required to meet the threshold to gain a seat, which hurt small parties like Mahachon which got 3% of the votes but no seat.

Implications

The nearly 60% increase in the number of party-list seats is set to benefit large, well-established parties, which in this case include only the Democrats and Pheua Thai. Smaller parties that rest largely on their leaders’ personal networks or reputation, such as Purachai’s Rak Santi Party, Chart Thai Pattana of the Silapa-Acha family or General Sonthi’s Matubhumi Party, are likely to do well in the constituency system, especially in each leader’s district. But voters tend to vote for major parties, who they believe should be forming the government, in the party-list system. It’s no wonder that when the Democrats proposed a change in the number of party-list seats earlier this year, Abhisit’s already shaky coalition nearly collapsed as all the coalition partners opposed the change. The proposal survived the joint parliamentary committee vetting draft panel only 18:17.[1] Moreover, an increase in party-list seats means a reduction in constituency seats as well as re-drawing the boundaries of electoral districts. Such re-districting also benefits larger parties that have the means and resources to get their vote canvassers out into these newly defined districts and garner support from voters.

The return of the single-seat constituency formula, which was used in the 2001 and 2005 elections, places large parties at a sizable advantage. True, small parties could have a shot at a seat by campaigning heavily in districts where they’re strongest, but that will likely not counterbalance the number of votes larger parties are set to gain. Dr. Parinya Tewarnnamitkul from the Law Faculty of Thammasat University has calculated that Chart Thai Party got 9.7% of the vote but only 18 MPs in the single-member constituency system used in the 2005 election. In 2007, however, the party received 30 MPs from 9% of the votes.[2] The 2005/2011 system essentially gives fewer MPs to small parties.

Yet it’s not all doom for small parties. As the Bangkok Post notes[3], “What favors small parties is the change from the multi-seat constituency used in the 2007 poll, to the single-seat format and the lifting of the 5% requirement of total votes for a party to be eligible to have MPs from the party list.” Perhaps, a small one-man show party like Rak Prathet Thai Party of Chuwit Kamolvisit – the massage parlor chao pho – could even get 1 party-list seat.

[1] The vetting committee consists of 19 Democrats, 15 MPs from other political parties and 11 Senators, without any representatives from the main opposition party, Peua Thai, which boycotted constitutional amendments (The Nation, January 13,2011).

[2] Matichon, “Parinya notes new electoral system puts small parties at a disadvantage; Puea Thai’s got advantage,” November 10, 2010.

[3] Bangkok Post “Amendments improve chance for smaller parties”, February 2, 2011

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss