We may never get full data on Thailand’s 2 February 2014 poll, so this is an attempt to make some sense of what is available. First, a health warning. These are unofficial figures leaked from the Election Commission. There have been three versions over the past three days, all slightly different. But the variations are not enough to affect this very simple analysis.

The figures show the turnout, valid votes, spoiled ballot papers, and the number who checked the “no vote” box in the constituency poll (I’ll call these last two combined the “protest vote”). The data exclude the 9 southern provinces where voting was not completed. They probably do not include the advance voting and the overseas vote.

Compared to the 2011 poll, the turnout is lower and the number of spoiled or “no” votes is higher.

| did not vote | spoiled ballot | “no vote” | valid votes | |

| 2011 |

25.0 |

4.3 |

3.0 |

67.7 |

| 2014 |

52.7 |

5.7 |

8.0 |

34.0 |

However, the difference is not really as dramatic as it appears. We can imagine that former Democrat voters (21.6% of the electorate in 2011) either did not vote or made a protest vote. Apart from them, 12% of the electorate that made a valid vote in 2011 either did not vote or spoiled their vote in 2014. That’s the real extent of the drop.

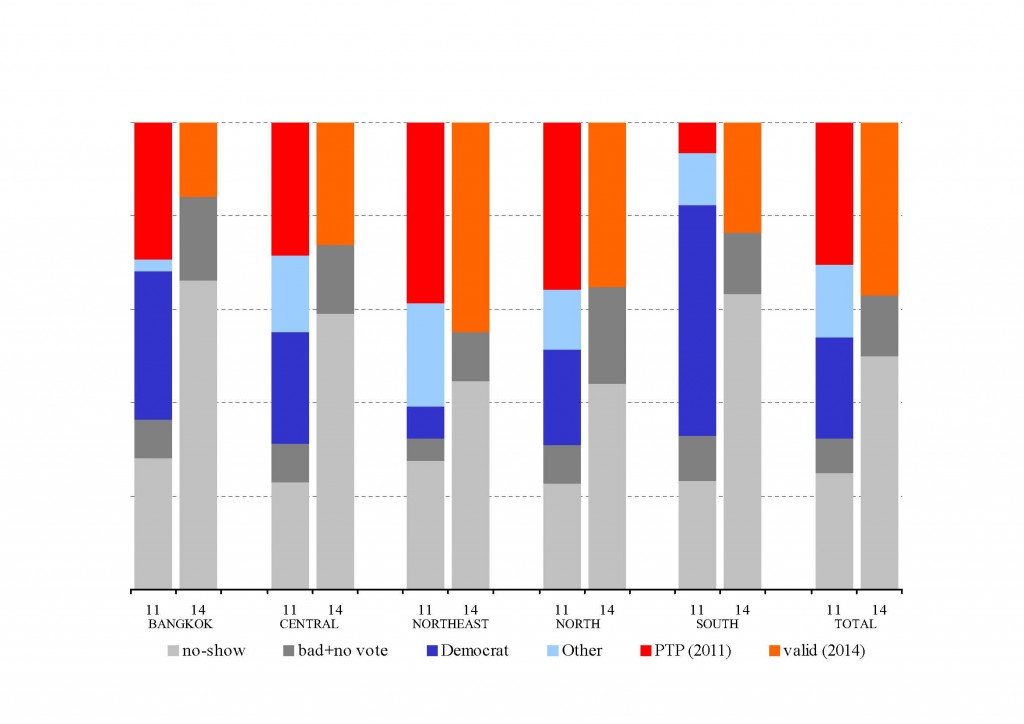

That drop shows in the two right hand columns of the first graphic. The Bangkok column for 2014 is wrong. The voting was abandoned in three constituencies, and only partially completed in two others. In the ECT figures used here, the total electorate figure includes all 32 constituencies, but the voting figures are for only 27 completed constituencies (or perhaps the 29 partially completed, we don’t know). So the 2014 Bangkok bar over-estimates the no-show. The figures for the south also don’t mean much as the 2011 bar is for the whole region, and 2014 for only 5 constituencies.

In the Northeast and the Upper North, the proportion of valid votes was higher than elsewhere. It is possible that in these two areas, the vote for Pheu Thai did not fall that much. Perhaps by 10-15 percent (at a guess). However, it’s worth pointing out that the protest vote was higher in the north than elsewhere, across all the provinces of the region (see the graphic below) and especially strong in the upper north, usually considered the Pheu Thai heartland. Why it was so is not clear.

In the Central region, the total valid vote in 2014 was less than the Pheu Thai vote in 2011. Given that Banharn’s party (and others) contested in 2014, Pheu Thai probably lost heavily here.

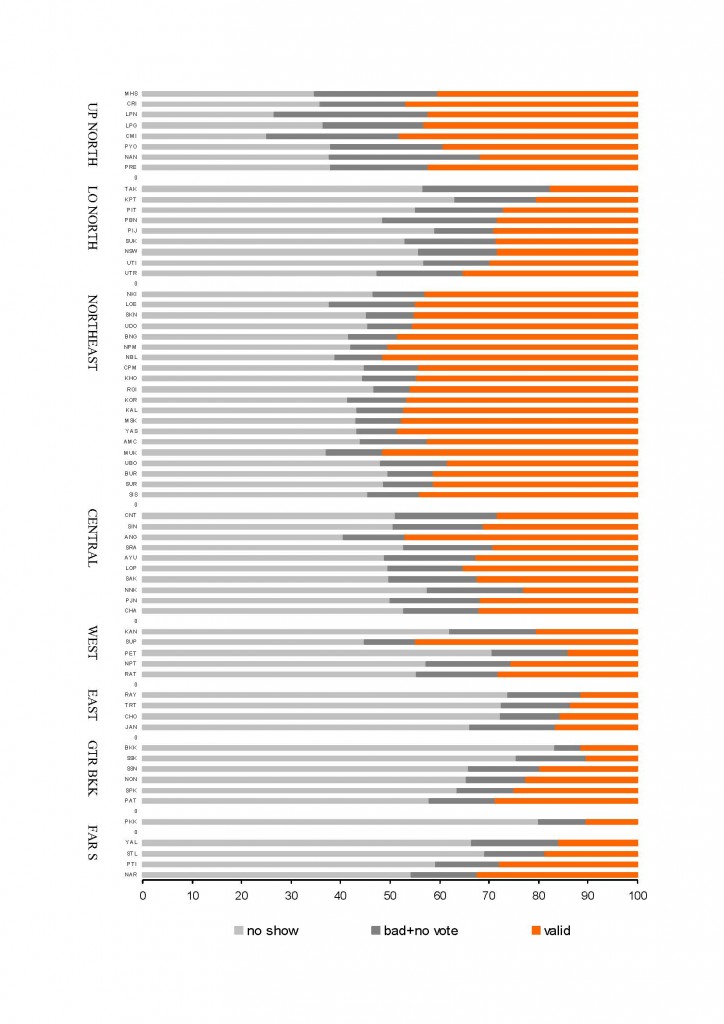

This second graphic shows the vote by province, roughly arranged from north to south. The orange bit is the valid vote, the dark grey bit is the protest vote (spoiled ballots plus “no vote” box) and the light grey bit shows those who did not show up to vote.

There were 7 provinces where the protest vote exceeded the valid vote: Samut Songkhram (where there has been a big movement against the government’s water scheme); three provinces in the east (Chanthaburi, Trat and Rayong); Phetburi; and Tak (by a massive amount).

My overall impression is that nobody won. If full data are every released, Pheu Thai will probably have won a majority of the seats. But the party cannot have won enough votes in absolute numbers to bolster the government’s sagging legitimacy. Last time, the party got 14.3 million votes in the constituency poll. At a guess, this time the figure would be around 10 million.

The “anti-vote” campaign of the Democrats and the PRDC did not triumph either. The protest vote was roughly double the usual level (14% against 7%), but dominant in only 7 provinces. Among former Democrat voters, more seem to have stayed away from the poll rather than registering a protest vote.

(With thanks to Khun Achara and Bangkok Pundit.)

Chris Baker is an analyst of Thai society and politics based in Thailand

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss