Small islands, sharply divided, give a conflict a certain focus and intensity—think Northern Ireland, Cyprus, East Timor. Sebatik Island, located off the northeast coast of Borneo, does not typically come to mind. But it is one of the few islands in the world cleaved in two by an international border. An unnaturally straight line, drawn by the Netherlands and Great Britain in 1891, now separates rivals Indonesia and Malaysia.

As a result, Sebatik’s inhabitants live a quaint transboundary existence. Some wake in an Indonesian bedroom and breakfast in a Malaysian kitchen. Citizens of both countries use the Malaysian Ringgit to trade at the nearest market town, Tawau, on the mainland of the Malaysian state of Sabah. Both are caught in the middle of an international conflict that has played out in minor local disputes and in litigation at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in the Hague.

It was on the basis of the Sebatik border that Indonesia made its claim to the small islands to the east, Ligitan and Sipadan. Malaysia’s claim to those islands relied on its guardianship of local turtles, in accordance with its Turtle Preservation Ordinance of 1917. In a 2002 ruling that had implications for the rights to nearby oil and gas reserves, the ICJ accepted the turtle argument, awarding sovereignty of the islands to Malaysia. But far from resolving tensions, the ruling fed into Indonesian narratives of perfidious Malaysia: a neighbour that conspires to take for itself Indonesia’s national heritage.

Further complicating matters, the Philippines also has a claim to Sebatik and its hinterlands. It had sought to intervene in the Sebatik case on the grounds that North Borneo is a region historically ruled by the Sultan of Sulu. An unwelcome reminder of this history came in February 2013 when a group of armed men from the Philippines—the “Royal Security Forces of the Sultanate of Sulu and North Borneo”—sailed out of the 19th century and into the Malaysian palm oil town of Lahad Datu, on the Sabah coast. The raid was swiftly repelled by the Malaysian armed forces, but the incident brought new light to a curious fact: Malaysia, since a 1963 agreement, has quietly paid the heirs to the Sulu Sultanate in the Philippines RM5,300 every year for its continued possession of Sabah—a payment the Malaysian government refuses to call “rent”.

These echoes of the colonial past, like so many footnotes to James Warren’s definitive history of the region, The Sulu Zone, are not mere academic distractions. They speak to an enduring geopolitical reality that renders the Indonesia–Malaysia–Philippines triborder a uniquely permissive environment for terrorists and other actors who, in alliance with ISIS or Darul Islam, are unlikely to call themselves “non-state”. It’s an environment that makes the border zone ground zero for what I would describe as terrorist arbitrage in Southeast Asia.

In economics, arbitrage at its simplest refers to the practice of buying a good in one market in order to sell it for a higher price in another. Although the strategy entails a transaction cost, it is one of little risk so long as the arbitrageur understands the prices in both markets—an informational edge. Theoretically, in a model that assumes arbitrage, discrepant prices should converge as arbitrageurs exploit the discrepancy for easy financial gain.

In Southeast Asia transnational terrorists engage in a type of triangular arbitrage to exploit the geopolitical differences between Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines. Instead of being motivated by profits, they seek to marshal scarce resources for attacks against their ideological enemies. In so doing, they rely upon their knowledge of the different costs of mobilising resources across a diverse region, the fragmented archipelagic geography of maritime Southeast Asia, and the failure of the three major states of the archipelago to cooperate in order to shut down arbitrage opportunities.

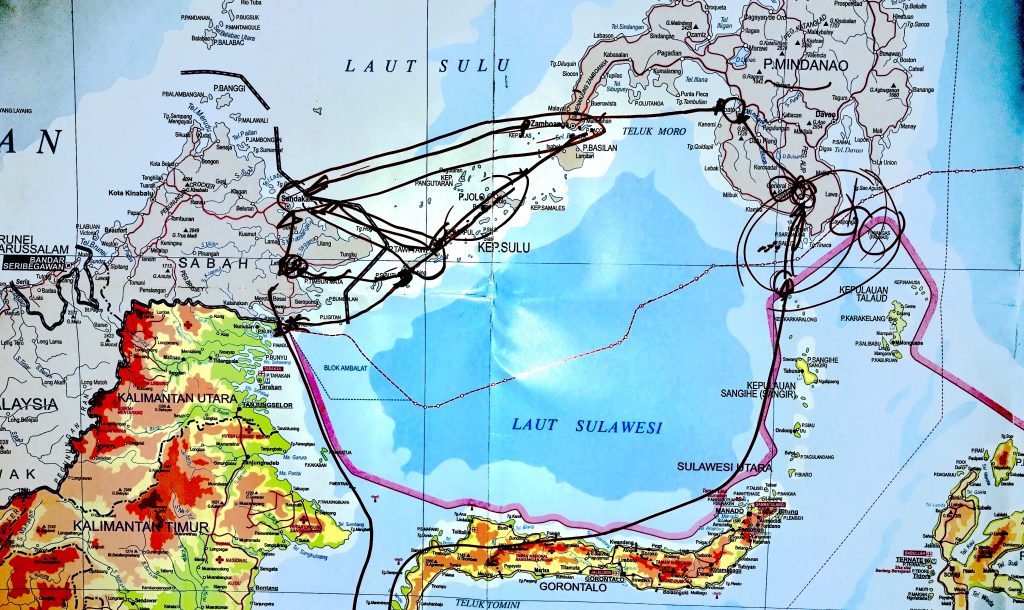

Most members of militant groups are not nimble arbitrageurs or entrepreneurs. But I’ve found in my research on the history of cross-border jihadism in the region that key transnational militants possess specialist knowledge of “market conditions” across the archipelago and the regional linkages they need to access them. Like the former senior Jemaah Islamiyah figure Abu Tholut—the Mantiqi III chief responsible for the triborder area in the 1990s—such highly mobile operatives know the byways and backwaters connecting Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines better than almost anyone.

Terrorists attempt two main types of arbitrage: input factor and regulatory. Input factor arbitrage occurs when terrorists leverage geographical differences in the distribution of factors needed to produce an attack. Due to the diversity of archipelagic Southeast Asia, island-hopping arbitrageurs might find, for example, that the cost of acquiring weapons is lower in the Southern Philippines (but higher in Indonesia), the cost of international travel is lower in peninsular Malaysia (but higher elsewhere), and access to high-value targets (foreign and local) is lower in Indonesia (but typically higher elsewhere).

These basic examples can also describe a form of regulatory arbitrage, in which terrorists exploit the differences between regulations and laws across states. The cost of international travel is low in Malaysia due both to its status as a hub for low-cost airlines and to the country’s lax immigration regime. The cost of weapons is high in Indonesia compared to the Philippines due both to the absence of a large armed insurgency in Indonesia and to Indonesia’s relatively strict gun control regime.

To return to Sebatik Island: the territorial tensions between Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines neatly play into the arbitrage strategies of terrorists. But not just because those tensions frustrate the ability of the three governments to cooperate against terrorists on the triborder—a fluid space at the centre of the Malay Archipelago that allows international travel in 360 degrees. To the extent that they reduce the ability of the major parties to cooperate more generally, regional tensions promise terrorists ongoing discrepancies across a fragmented geopolitical seascape, presenting myriad opportunities for arbitrage that seldom escape their notice. Such opportunities will remain open so long as states are unable to work together to even out discrepancies or to raise barriers to arbitrage.

Recently, a number of positive attempts have been made to increase regional cooperation, including trilateral maritime patrols. But such efforts are in their infancy. One sign of the continued lack of trust between Malaysia and the Philippines is the failure to work together to ascertain the identities of dead militants. Malaysian militants—who are important in an arbitrage scenario because, among other factors, the cost of fundraising is relatively low in Malaysia—were crucial to the coalition that captured the Philippine city of Marawi under the banner of ISIS. Yet, to date, the Philippines authorities have failed to request a DNA sample from the Malaysians that would allow them to cross the key financier of the Marawi attack, Dr Mahmud Ahmad, off everyone’s list. The same has occurred in other cases, so that militants, whose aliases and kunya are deceptively effective, might ghost through the region unmolested.

Still no regional structure exists for authorities to map how militants mobilise across national borders. Jihadists in Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines are each embedded in distinct and dynamic local networks that facilitate transnational mobilisation. In a July 2017 report, the Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict (IPAC) recommended short courses in which counterterrorism officials from all three countries might learn from “real case studies of cross-border extremism”. Taking up the idea, in December officials from the three countries met at a workshop hosted by the Jakarta Centre for Law Enforcement Cooperation (JCLEC). But due to the failure of officials from all three to sign off on the case study program, the practical mapping of transnational linkages was replaced by a series of standard presentations.

It is a truism that while terrorists slice through international borders, counterterrorists are “contained” in nation-states. But it is failure to understand transnational linkages that allows militants to maintain their critical informational edge. In terrorist attacks, such linkages act as a force multiplier, allowing processes of arbitrage and collaboration through which key actors aggregate and deploy resources that they might have otherwise lacked. The scenario is analogous to that of a corporation seeking to establish a transnational production chain for a new product. The “product” in this case, a novel attack, has the potential to catch local authorities by surprise because it is the result of a combination of factors, some of them from beyond the horizon.

The January 2016 Jalan Thamrin Starbucks attack in Jakarta, in which four civilians were killed, might have been a massacre were it not for a chance failure of arbitrage. A key arbitrageur in the Jamaah Anshorut Daulah network, the weapons smuggler Suryadi Mas’ud, abandoned his task to bring multiple automatic rifles into Indonesia from the Philippines via the Sanghie-Talaud island chain. Others who then attempted to complete the job failed to get the weapons to Java.

But such a failure shouldn’t make anyone complacent. It is common for terrorists to work through a process of trial and error, until at some point they succeed. The prospect of a mass casualty light arms attack in a crowded space remains the greatest terrorist threat in Indonesia. The risk of such an attack can only be higher than it was in 2016, with hundreds of militants, now experienced in urban warfare, returning from former ISIS strongholds in Syria and Marawi.

In practice, arbitrage is far from frictionless or risk-free, as the case of Suryadi Mas’ud, who was arrested last year in West Java, illustrates. Transaction costs may pose a significant barrier. Yet in a globalising world marked by a strong pattern of regionalisation, the cost of arbitrage will only decrease as general Southeast Asian integration proceeds. As Pankaj Ghemawat has found in his work for the logistics company DHL, “East Asia & the Pacific” is second only to Europe in intraregional connectedness, with Southeast Asian countries receiving unexpectedly high global connectedness scores.

Increased connectivity was a factor in last year’s attack on Marawi. While some jihadists used traditional sea routes through the triborder to get to the Southern Philippines, perhaps even more took advantage of the growth in low cost regional air travel. Regional airlines now connect a surprising schedule of provincial capital cities in the region with domestic or international flights to other provincial capitals—or to national capitals, like Manila.

Marawi: returning to a destroyed city

Mishandling the return of civilian evacuees risks creating new pockets of sympathy for violent extremist groups.

But low numbers of key transnational actors have always driven the most serious terrorism in Southeast Asia. The archetype is the former Indonesian militant Hambali. When Hambali was arrested in 2003, the threat to the region was much reduced, partly because he was a unique link to al-Qaeda, but also because he uniquely understood how to exploit geopolitical differences across Southeast Asia. As the arbitrage model suggests, terrorist “markets” no more encourage large numbers of arbitrageurs than do traditional markets. An arbitrage opportunity might only attract a few geographically flexible actors capable of understanding conditions in more than one country at a time. Southeast Asia will continue to be vulnerable to transnational terrorism until there are at least equal numbers of counterterrorism officials who can do the same.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss