The 2004 and 2009 General Elections saw no significant decrease in the number of election irregularities. The Association for Election and Democracy, Perludem, found that irregularities included money politics, vote-counting manipulation, taking advantage of bureaucratic positions for campaigning, and intimidation. The amount of invalid votes, for example, rose from 3.3% (1999), 9.7% (2004), to 14.4% (2009).

Based on the news in the past months, it’s safe to say that violations still persist in 2014.

However, there is something significantly different: in the aftermath of the 2014 elections, civil society organisations and citizens are using the internet and communication technology (ICT) to push for transparency.

After the Presidential Elections, precisely on 11 July, a Twitter user with 7,000 followers began posting C1 forms used for voting tabulations. Other users followed suit, and started openly scrutinising scanned forms from voting stations across the country that were uploaded by KPU. After three hours, the influx of crowdsourced forms was so overwhelming that the initiator ended it.

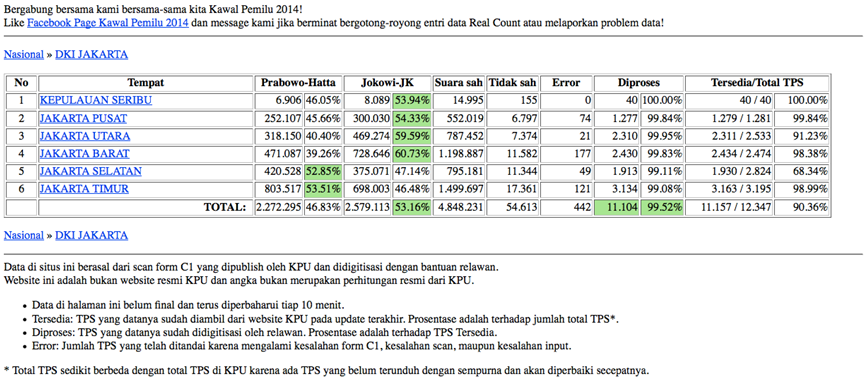

On 12 July, the application Kawal Pemilu (Guard the Elections), also initiated by civilian internet users, was launched, The application facilitates internet users to crowdsource voting tabulation from across the country, or in their words gotong royong entri data (collective data entry), in order to monitor the voting recapitulation until 22 July 2014. The website is also linked to a Facebook page that updates every 10 minutes. While the website facilitates tabulation, the Facebook page disseminates information.

Source: “DKI Jakarta”. Kawal Pemilu, retrieved July 15, 2014 from http://www.kawalpemilu.org/#0.25823

On 16 July, Tempo.co reported that hundreds of hackers attacked Kawal Pemilu. The attack, which predominantly came from within Indonesia, was aimed to weaken the website’s credibility because it was rapidly gaining popularity – and legitimacy – as a reference to monitor the vote recapitulation process.

Kawal Pemilu is an organic online social movement, and is indeed effectively pushing for more transparency in the vote recapitulation process. However, the very nature of organic movements is that they are not always well-organised enough to leave a lasting and deep political impact.

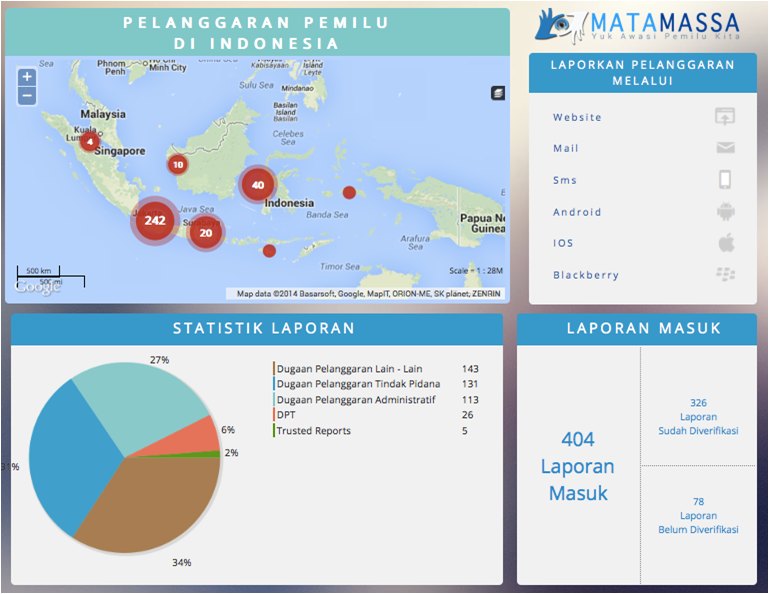

But there is a more organised approach to monitor the 2014 General Elections. The application Mata Massa, or ‘Eye of the Masses’, was launched to facilitate polling watchdogs and ordinary citizens who use their smartphones to monitor the General Elections. Its 200 organizers received at least 1,500 reports and contributed 1,300 out of approximately 8,000 reports received by General Elections Monitoring Body (Bawaslu) during the Legislative Elections. They also set up a verification process to ensure the administrative accountability of these reports before their submission to Bawaslu.

Unfortunately, these reports have yet to be responded to by Bawaslu in a way that would not demotivate citizens to take part in monitoring the elections. This highlights the fact that even with verified reports of violations, Bawaslu still needs support to act on them and hold violators responsible.

Source: “Homepage”. Mata Massa, retrieved July 15, 2014 from http://www.matamassa.org/

More support is also needed for organic and organised monitoring efforts that mobilise citizens and reveal weaknesses within the election system in order to help correct them. This means taking note as well on how ICT has been used in offline contexts to monitor the elections.

During the Legislative Elections, smartphones and social media have been used by monitoring bodies to organise themselves better in the field. The largest monitoring body registered with the General Elections Committee (KPU), the People’s Voter Education Network (JPPR), trained their field monitors to utilise ICT in overcoming challenges they face. When a field monitor faces direct intimidation, it becomes life threatening for them to continue the report on to Bawaslu. Instead, they tactically used ICT to ‘mention’ allies and members of the General Elections Monitoring Body (Bawaslu) on Twitter to, at the very least, raise awareness.

Other civil society-initiated websites were also set up during the Legislative Elections to provide information for voters on the candidates’ background, and recommend candidates with clean records. Among the most prominent is Jari Ungu (Purple Finger), Perludem’s API Pemilu, and Bersih 2014 (Clean 2014) which was initiated by a consortium of civil society organisations.

These online social movements during the 2014 elections show that citizens are sharing knowledge, information and expertise, and often form allies with mainstream media and journalists to guard their democracy. The nature of crowdsourcing through collective public scrutiny also protects citizens from direct intimidation, commonly experienced by field monitors.

By processing the wealth of data submitted voluntarily by internet users, citizens can partner with the government to make sure good policies are in place and upheld. We should thus think about how to extend citizen monitoring beyond current elections, and how to integrate it into the formal system in order for it to leave irrevocable reforming effects.

After all, with more eyes on the ball, it’s clearly more difficult to rig the match.

…………….

Inaya Rakhmani is the Head of the Communication Research Centre, Universitas Indonesia and an associate at the Asia Research Centre, Murdoch University

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss